Few States Get Good Grades on Mental Health Care

Although some improvements have been made in the mental health care that states offer, a recent report from the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) found that overall psychiatric care in the United States remains caught in the “stranglehold” of rising demand and limited resources.

NAMI conducted a nationwide grading of the states in 2008 and 2009 and released its findings in a “report card” on March 11. The organization reported that there has been little systemic improvement in the mental health care system since its last look at the states that was released in 2006 (Psychiatric News, April 21, 2006).

“Overall this shows that the President's New Freedom Commission's call for fundamental transformation was not heard,” said psychiatrist and NAMI President Anand Pandya, M.D., in an interview with Psychiatric News.

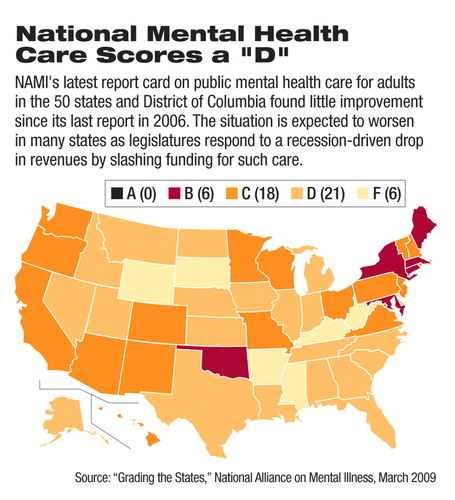

The report assessed the nation's public mental health care system for adults and found that the national average grade is a disappointing“ D,” just as it was in 2006. The report card was based on both state-government surveys of available services and computer searches of the availability of information and treatment services in each state, conducted in 2008 and early 2009.

The findings, based on 65 specific criteria such as access to medicine, housing, and family education, led NAMI to the conclusion that services had actually degraded in 12 states over the last three years.

“Even states that made progress are, because of the [economic] downturn, at risk of losing ground,” said Pandya, who cited reform efforts of the Virginia public mental health system following the April 2007 killing of 32 students and faculty at Virginia Tech by a student with serious mental illness who later killed himself. However, the recession has led Virginia's legislature to provide little of the funding needed to enact the authorized reforms.

The impact of the ongoing recession on mental health services was echoed by Michael Fitzpatrick, executive director of NAMI, who noted that state budget cuts are coming at precisely the time when the need for psychiatric care is spiking due to the economic stress that is spreading in the general population, particularly that caused by growing unemployment.

Cutting back on mental health services funding is part of “a vicious cycle that can lead to ruin,” Fitzpatrick said. “States need to move forward, not retreat.”

Robert Feder, M.D., an APA Assembly representative from the New Hampshire Psychiatric Society, said budget cuts in his state have resulted in the loss of housing for people with mental illness and psychiatrist positions at community mental health centers. The result of funding cuts has been a reduction in the overall mental health care available in New Hampshire, which received a “C” grade.

“My fear is that people who are not getting the help they need in the mental health system are going to end up in the prison system,” Feder said. “So I don't know if the state is going to end up saving any money.”

Marcia Goin, M.D., Ph.D., vice chair of APA's Council on Advocacy and Public Policy and a former APA president, said the low grades in the report will not surprise anyone who works in the public health care sector.

The grades “reflect what we see,” said Goin, a psychiatrist in California, which received a “C.”

Not all states have joined the cost-cutting trend at the expense of their NAMI grades. Among the highest scoring states were Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, and Oklahoma, which all received a“ B.” Oklahoma also was among the most improved, moving from a“ D” in 2006. No state earned an “A.”

The lowest-scoring states were Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Dakota, West Virginia, and Wyoming, all of which received failing grades.

Among the specific shortcomings identified in the report was the lack in most states of public health insurance plans that meet the needs of people with serious psychiatric illness. States also frequently fail to provide adequate amounts of “lynchpin” services, such as integrated substance abuse and mental health services along with hospital-based care when needed.

Few states have invested in or even developed plans for long-term housing for people with serious mental illness.

The almost total lack of supportive housing for people with mental illness in Illinois is a “huge problem,” said Joan Anzia, M.D., a member of the APA Council on Advocacy and Public Policy. The state, which received a“ D” grade, eliminated four community psychiatric outpatient clinics over the last six months and plans further cuts this year.

Among improvements since the 2006 report, NAMI found that states are more likely to offer effective diversion programs to people with psychiatric illness from the criminal-justice system, but such programs are often implemented by county governments without effective state leadership, the report pointed out.

Other findings include a widespread “information gap” in many states, where few data are collected by either federal or state mental health administrators regarding the performance and effectiveness of the state systems.

The authors criticized the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in particular for failure to provide adequate leadership in the development of uniform standards for collecting state, county, and local data.

“The problem starts at the federal level,” said Ron Honberg, director of policy and legal affairs at NAMI. “We need leadership from the federal government like never before.”

Among the steps needed to improve care, according to the report, is increased public funding for mental health care services through“ modest” tax increases and dedicated trusts. Systemwide improvements have been limited by the continuing lack of treatment and effectiveness data through standardized collection within and across states. Specifically, the authors called for better reporting on evidence-based mental health treatment practices and tracking waiting times in emergency rooms.

Psychiatrists likely are already aware of many of the shortcomings of the state mental health systems within which they work, including the lack of patient-centered care, Pandya said. However, he hoped that the report will provide more comprehensive information on the needs of each state that psychiatrists can use to advocate for improvements where they live and work.

“Grading the States 2009” is posted at<www.nami.org/gtsTemplate09.cfm?Section=Grading_the_States_2009>.▪