What Rats Can Tell Us About Stress-Related Sex Differences

Abstract

Women are known to be more susceptible to stress and stress-related psychiatric disorders such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder than men.

One possible explanation for this gender difference may have been found in an animal study reported June 15 in MolecularPsychiatry.

The research, led by Debra Bangasser, Ph.D., a behavioral neuroscientist at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, focused on corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), a primary mediator of the stress response in the brain, and more particularly, on neuron receptors for CRF.

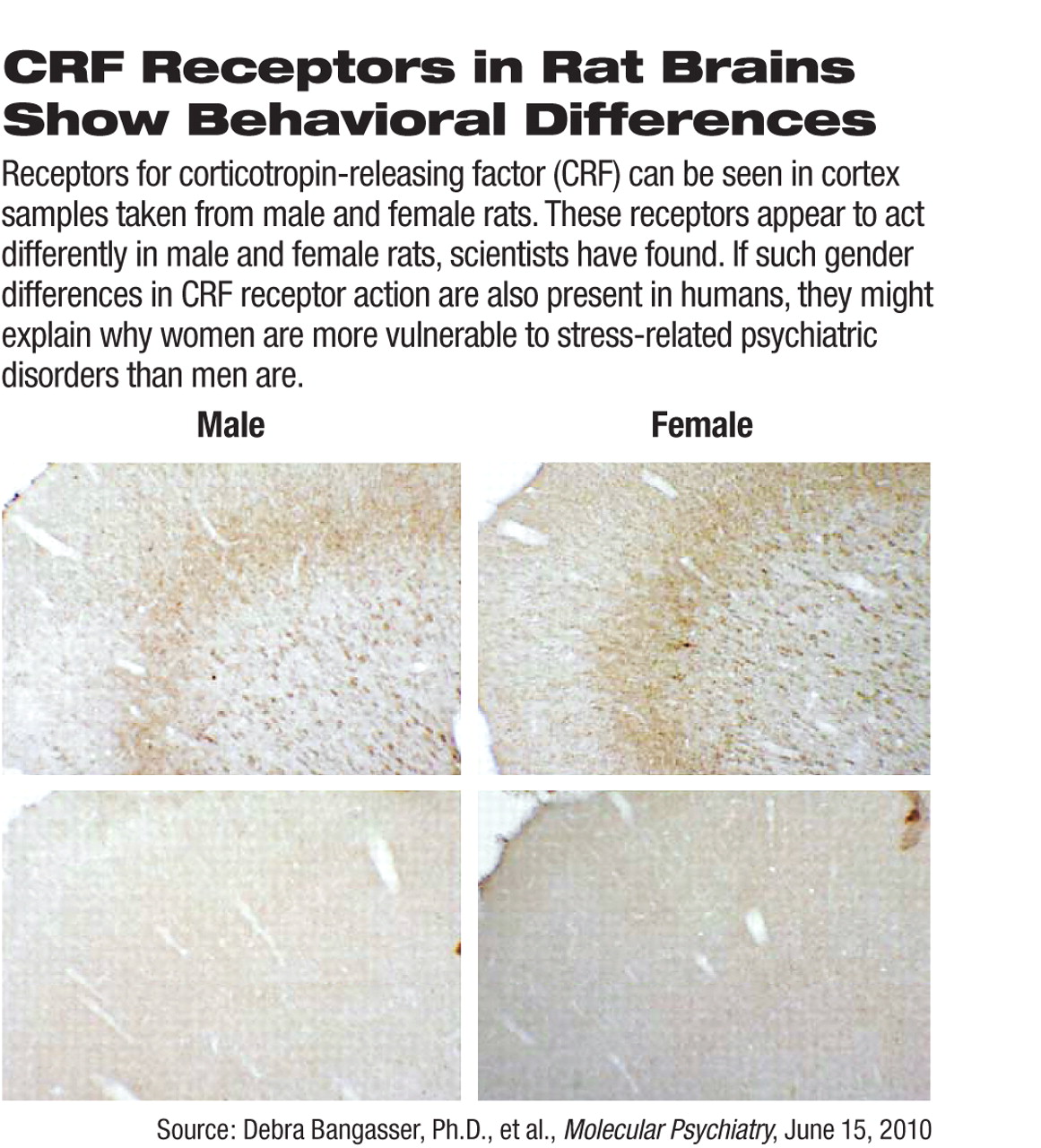

The researchers took cortical samples from male and female rats that had not been previously exposed to stress and examined the CRF receptors on the rats' neurons. CRF receptors on neurons from the female rats were bound more tightly to cell-signaling proteins than the CRF receptors on neurons from the male rats were. This finding implied that neurons from the female rats would be able to respond to CRF to a greater degree than neurons from the male rats.

Cortical samples were also taken from male and female rats that had been previously exposed to stress and examined with regard to the behavior of CRF receptors on neurons. The receptors from the male rats, but not from the female rats, were found to have moved inside the neurons, purportedly to protect themselves from excessive CRF stimulation.

“Together, the findings identify molecular and cellular mechanisms that could result in enhanced sensitivity of female rats to CRF and a decreased ability to adapt to excessive CRF,” the researchers said.

In the event that the results from this animal study can be extrapolated to humans—which, of course, is not always the case with animal studies—then they might help explain why women are more vulnerable to stress and the stress-released disorders of depression and PTSD than men, the researchers believe.

The study was funded by the U.S. Public Health Service.

An abstract of “Sex Differences in Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Receptor Signaling and Trafficking: Potential Role in Female Vulnerability to Stress-Released Psychopathology” is posted at <www.nature.com/mp/journal/vaop/ncurrent/abs/mp201066a.html>.