Learn How to Enjoy Every Moment in Paris

Abstract

Timed use of bright light and melatonin, along with shifting sleep earlier or later before departure, can foster a traveler's daytime performance and sleep on arrival in a new time zone, according to Charmane Eastman, Ph.D., a professor of behavioral sciences and director of the Biological Rhythms Research Laboratory at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

Diplomats, lawmakers, military commanders, and their support staffs are among those for whom escaping the discomfort and fogginess of jet lag holds high priority, Eastman said in a talk for the Congressional Biomedical Research Caucus in Washington, D.C., in September.

Physicians, business travelers, athletes, musicians, and others whose work takes them around the globe also can benefit from using jet-lag countermeasures, Eastman told Psychiatric News.

Jet lag results from a temporary misalignment between the body's internal clock and the demands of the destination time zone. Disturbed nighttime sleep and diminished daytime alertness rank highest among travelers' complaints. Dysphoric mood and digestive upsets also occur frequently.

Symptoms ordinarily persist about a half day to one day for every time zone crossed, but can last longer or dissipate faster, Eastman said, depending on the time of outdoor light exposure.

Most people find it harder to travel east, which asks them to fall asleep earlier, relative to home time, than to travel west, which calls for staying up later.

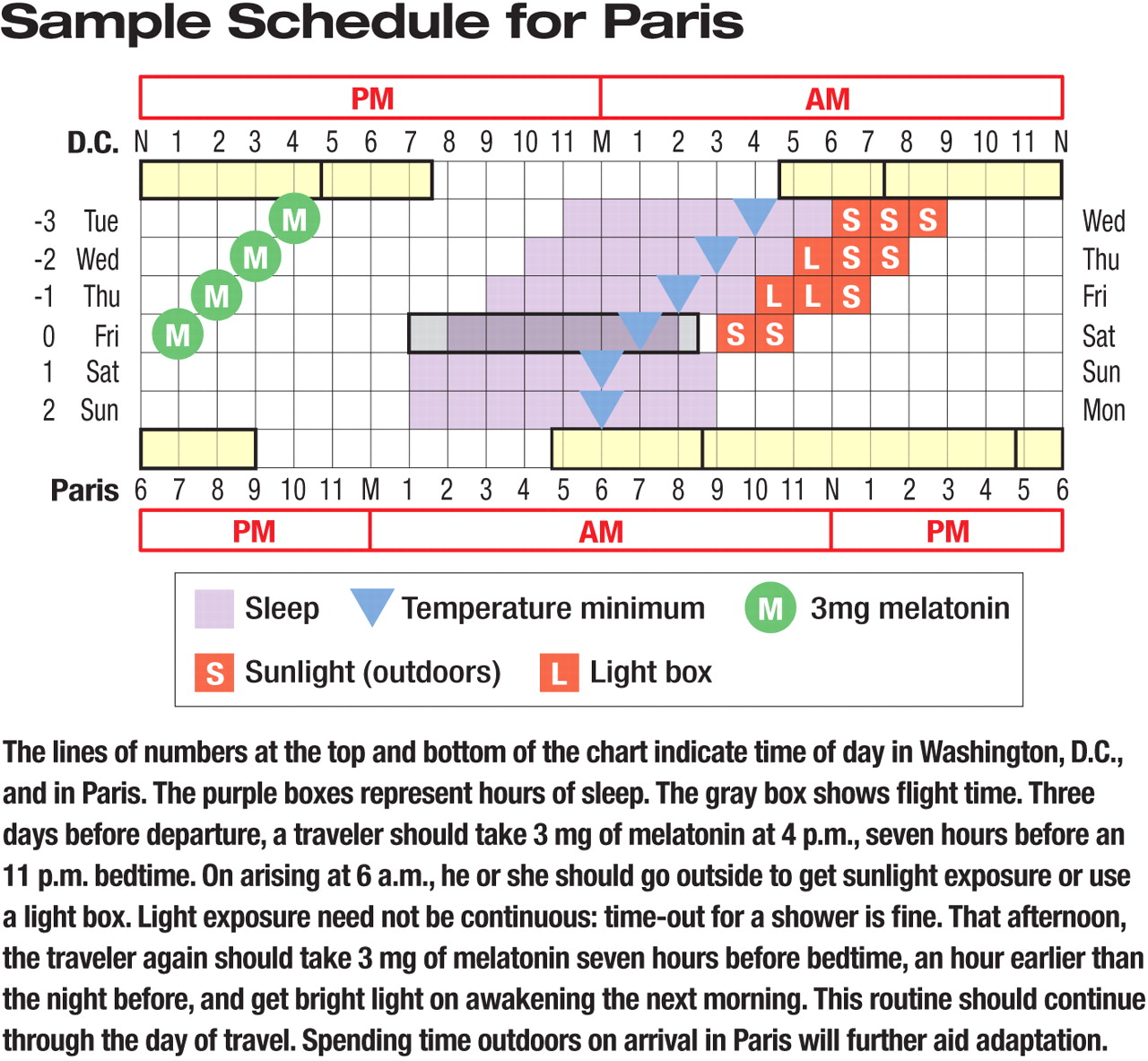

Bright light, obtained outdoors or from a light box, and exogenous melatonin advance or delay the body clock depending on their time of administration, Eastman said. Light exposure before the body's temperature minimum—about 4 a.m. in people who usually wake between 6 a.m. and 7 a.m.—pushes the internal clock later. Light exposure after the temperature minimum shifts the clock earlier.

When the temperature minimum occurs in waking hours, as commonly occurs after eastward travel, cognitive performance and manual dexterity often deteriorate, Eastman noted. Jet-lag countermeasures aim to keep the temperature minimum in sleep or to realign it quickly with sleep.

While the hormone melatonin is secreted only in the dark, taking exogenous melatonin in the afternoon shifts the biological clock earlier. Taking it in the morning shifts the clock later.

Although melatonin is neither a sedative nor a hypnotic, it may increase sleepiness. New users of melatonin should take test doses at home, Eastman said, and avoid driving afterward.

In her talk, Eastman focused on a trip familiar to her audience—one from Washington, D.C., to Baghdad, with a stopover in Germany, a shift of eight time zones east in winter, and seven in summer, when Daylight Saving Time is in effect. Shorter trips eastward employ the same principles to hasten adaptation. The chart above shows how to prepare for a trip from Washington, D.C., to Paris.

Eastman occasionally designs jet-lag prevention schedules for travelers in return for daily feedback on their progress. She can be contacted at ceastman@rush.

More information can be found in Eastman's review, “How to Travel the World Without Jet Lag,” in the June 1, 2009,Sleep Medicine Clinics,posted at <www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2829880/>.