Psychiatrists Devoting Time to Treating Homeless

Abstract

Last fall, a stocky older man could often be seen standing on the corner of L and 22nd streets, N.W., in Washington, D.C. His name was “Colonel Sanders,” he told this reporter, and he proudly informed her that he had attended Cambridge University in England, had fought in both Iraq and Afghanistan, and was still active in the military. “Look out there!” he exclaimed. “Can you see those red, blue, and yellow helicopters? I'll be boarding one of them in a few minutes.”

“Colonel Sanders,” who presumably had schizophrenia and was homeless, nonetheless indicated after several encounters that he was reasonably content with his delusional world.

Unfortunately the same cannot be said about most of the estimated 1 million or so Americans who have a mental illness but no place to call home (see How Many Americans Have a Mental Illness, but No Home?). So what is being done to help this disenfranchised population?

Perhaps more than one would expect, authorities on the subject say.

For example, during the 1980s, few psychiatrists worked at places where people who were mentally ill and homeless received services, such as shelters or drop-in centers, or with outreach teams, Van Yu, M.D., medical director of the Center for Urban Community Services in New York City, reported during an interview. But since then, more and more have done so, he said, and because of various initiatives.

One is the Project for Psychiatric Outreach for the Homeless. It got its start in 1986 as a task force of an APA district branch and since then has taken off, he noted. In fact, Yu has headed the project since 2003, and it is now part of the Center for Urban Community Services.

Stephen Goldfinger, M.D., chair of psychiatry at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center and a longtime advocate for people who are mentally ill and homeless, concurred with Yu that the project has come a long way from its modest inception. “When I first got involved with the project, there were a couple of volunteer docs, and we had our first meetings in the living room of one of them. The project now has multiple full-time psychiatrists.”

Another initiative that has increased the number of psychiatrists working with homeless mentally ill individuals in recent years is a training session offered at APA's annual Institute on Psychiatric Services. The session is run by Goldfinger and other psychiatrists. “We probably train 80 residents or medical students each year,” he estimated. “So in 10 years, that means we have trained something like 800 clinicians.”

In 1999, the Psychiatric Foundation of Northern California launched a project to help mentally ill homeless people in San Francisco. By 2003, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers participating in the project had helped some 300 individuals (Psychiatric News, July 18, 2003). Now, seven years later, the project is still “alive and well,” Mel Blaustein, M.D., president of the foundation, said in an interview, “and it also includes a bicultural aspect where we're working with Latinos and illegal immigrants.”

More efforts are likewise being made today than a decade or two ago to find supportive permanent housing for people who are mentally ill but without a home, M. William Sermons, Ph.D., director of the National Alliance to End Homelessness Research Institute in Washington, D.C., said. “This is happening around the country. There are lots of communities, big and small, that are doing things. For example, Pathways to Housing was established in New York City in 1992 to provide housing first, and then treatment, to mentally ill homeless people. Quincy, Mass., has done a pretty remarkable job in scaling up its housing-first-and-treatment-next strategy. Another place is Maine, both in Portland and rural areas. Still another is Seattle, with a housing-first intervention called 1811 Eastlake.”

But are these efforts making a difference? Numbers and progress reports indicate that they are.

Model Reaping Success

“We are working in three cities directly now,” Sam Tsemberis, Ph.D., founder of Pathways to Housing, reported. “We run programs in New York City, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia. Currently we are serving some 1,000 people.” But since the program was launched in 1992, it has actually housed many thousands of individuals who were mentally ill and without a home, and then has provided them with mental health services subsequently, he said.

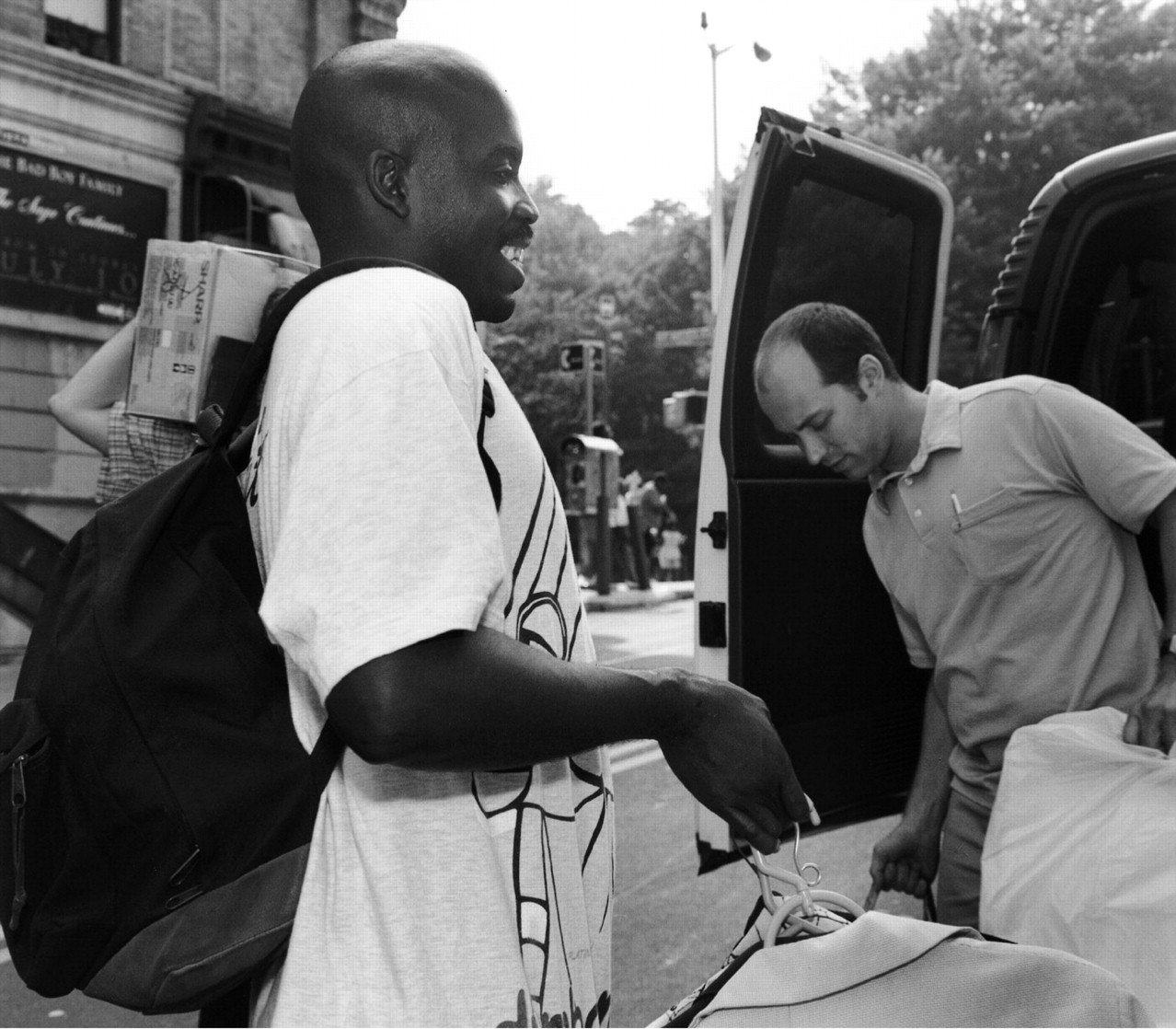

James Fatal, a New York City homeless man with bipolar disorder, moves into an apartment with the help of Bradley Jacobs, a Pathways to Housing service coordinator. “It feels good,” said Fatal, “to finally be housed and out of the cold.” That was a decade ago. Fatal is still living in his apartment and was recently promoted to assistant team leader for the West Harlem Assertive Community Treatment team.

Further, Pathways to Housing is adding medical services to its mental health services and is helping tenants who are aging remain in place, Deborah Padgett, Ph.D., a professor of social work at New York University, noted.

The Pathways to Housing model has been replicated in 40 or 50 cities throughout the United States, Tsemberis pointed out. He and his colleagues are providing technical assistance to a number of these projects.

According to a survey conducted by the U.S. Conference of Mayors and published in December 2008, all but one of the cities surveyed had developed or was developing a 10-year plan to end homelessness. These efforts are bearing fruit. For example, Miami's 10-year plan helped lead to a 66 percent decline in homelessness between 2003 and 2008.

Indeed, “supportive housing has been shown over and over again to have good outcomes for formerly homeless mentally ill people,” Yu attested. “Their psychiatric status gets better, they have fewer hospital days, their health status gets better,” among other positive changes.

Individual stories likewise suggest that efforts to help homeless mentally ill people are making a difference.

Dog Sitting Paid Off

“Henry,” an alcohol-dependent homeless man in East Harlem, continually rebuffed efforts by Yu's outreach team to help him. But one day, the police came to take him to the local police precinct on public-nuisance charges. The outreach team agreed to look after his dog until he returned. After he returned, he agreed to work with the team. “After all,” he said, “you cared for my dog, so I feel I have to work with you.” Thanks to this collaboration, he not only managed to deal with his alcohol problem, but also obtained supportive permanent housing for himself and his dog.

“Let's say you see somebody on the street who is obviously homeless and symptomatic—muttering to himself, disorganized, sitting next to several shopping bags, very vulnerable, very confused, not capable of doing much at all,” Tsemberis proposed. “But then you place him in his own apartment, with a bathroom to wash in, a bed to sleep in, and storage cabinets for things that were in his shopping bags, and then you provide him with mental health and other support services. He can be transformed remarkably fast. It is very dramatic.”

As part of his outreach work, Yu learned that a man sleeping in a park on the Upper East Side of Manhattan—“Bill”—was depressed. Yu offered him antidepressant medication. Bill took it and thanked him. Yu told Bill to come to his office the following week for more treatment. Bill did. And sometime later Bill received supportive permanent housing as well. These days Bill stops by Yu's office from time to time to say, “Doc, how are you doing? I just wanted to say hello and to tell you that I'm doing really well.”

Nonetheless, colossal challenges remain to help this population. The single-adult population that has both a serious mental illness and no home has been reduced dramatically in New York City, Yu reported. But the number of homeless families with a member who has anxiety, depression, or other mental illnesses has shot up by comparison (Psychiatric News, June 6, 2003).

“Even though more psychiatrists are now working with mentally ill homeless people than a few years ago, there is still a shortage of them,” Hunter McQuistion, M.D., director of community psychiatry at St. Luke's and Roosevelt Hospitals in New York City, said. One reason is that “it takes a very special psychiatrist to be able to work outside of a medical culture.” And “even if a psychiatrist is paid adequately, the resources for the rest of the program may not necessarily be robust. It can yield frustration and burnout....”

Although psychiatrists have learned more about how to work with this population during the past few years, McQuistion added, they still haven't created a set of best clinical practices for their work. “I don't want to manualize it, but we haven't articulated it as clearly as we should so that people in the field have a good idea of what works and what doesn't. That's the next phase.”

Regarding ending homelessness among mentally ill individuals, Tsemberis observed, “I think the difference between a decade or two ago and now is that we now actually know what to do. There are several different program approaches that are very effective in ending homelessness for these people. The most effective ones typically begin with supportive housing, as we're doing.... It's not as if we're working in an area like schizophrenia or cancer and don't know the cure.... So it's not a question of medical science, but of societal values and political will ... to end this terrible disgrace of homeless people, especially with mental illness, on the streets.”

Goldfinger agreed. “Model [supportive permanent housing] programs only solve the problem for the few people who get to live in the models. In that sense, things are not much better than 25 years ago when the first APA task force report on homelessness and mental illness was issued.”

What Goldfinger would like to see happen in the United States is what happened in Sweden. “If you look around there, almost nobody is homeless. The elderly live in reasonable, decent housing, health care is free for all, and the tax rate is 60 percent or so. That's fine with me. But try selling that to the rest of America!”