Personality Disorder Symptoms Not Depression Artifact

Abstract

A personality disorder that presents during depression is likely to be “the real thing.”

A multisite, six-year longitudinal study of depression and comorbid personality disorders appears to confound longstanding clinical lore by showing that symptoms of personality disorder are a valid reflection of personality pathology and not simply an artifact of depression.

Six-year outcomes for patients with comorbid personality disorder and major depressive disorder at initial evaluation were similar to those of patients with only personality disorder and significantly worse than those of patients with only major depressive disorder, according to the report “State Effects of Major Depression on the Assessment of Personality and Personality Disorders.” It will appear on AJP in Advance, the advance online edition of the American Journal of Psychiatry, on February 16.

“For many years in the field, there has been a presumption that mood effects that are transitory really influence how someone perceives the world and themselves to the degree that it would distort any information about their personality traits,” lead author Leslie Morey, Ph.D., told Psychiatric News. “But our analysis provided no evidence to suggest that what was being evaluated as a personality disorder at baseline was anything but personality pathology.

“In every way, patients with both depression and symptoms of personality disorder at baseline resembled people with pure personality disorder six years later. There was no evidence to support the presumption that what clinicians are picking up at baseline is an artifact related to depression.”

Morey is a professor and chair of the Department of Psychology at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas.

Morey and colleagues analyzed six-year outcome data from the multisite Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (CLPS), a multisite prospective naturalistic longitudinal study. Numerous analyses of CLPS have appeared in the literature; a description of the study “The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: Development, Aims, Design, and Sample Characteristics” appeared in the winter 2000 Journal of Personality Disorders.

In the current analysis, 433 subjects from the CLPS study were assigned to three groups: a “personality disorder only” group of 119; a “pure depression only” group of 73; and a comorbid group of 241 patients with personality disorder plus major depression.

At baseline, an interviewer administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders–Patient Version (SCID) and the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders. There were no differences at baseline between the “personality disorder plus major depression group” and the “personality disorder only” group in the degree of personality pathology.

Participants were reinterviewed after six and 12 months and then yearly thereafter for five more years.

At year 6, a comprehensive evaluation was conducted that included the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders as well as the Neuroticism-Extroversion-Openness (NEO) Personality Inventory, the Global Assessment of Functioning, and the Personality Assessment Inventory.

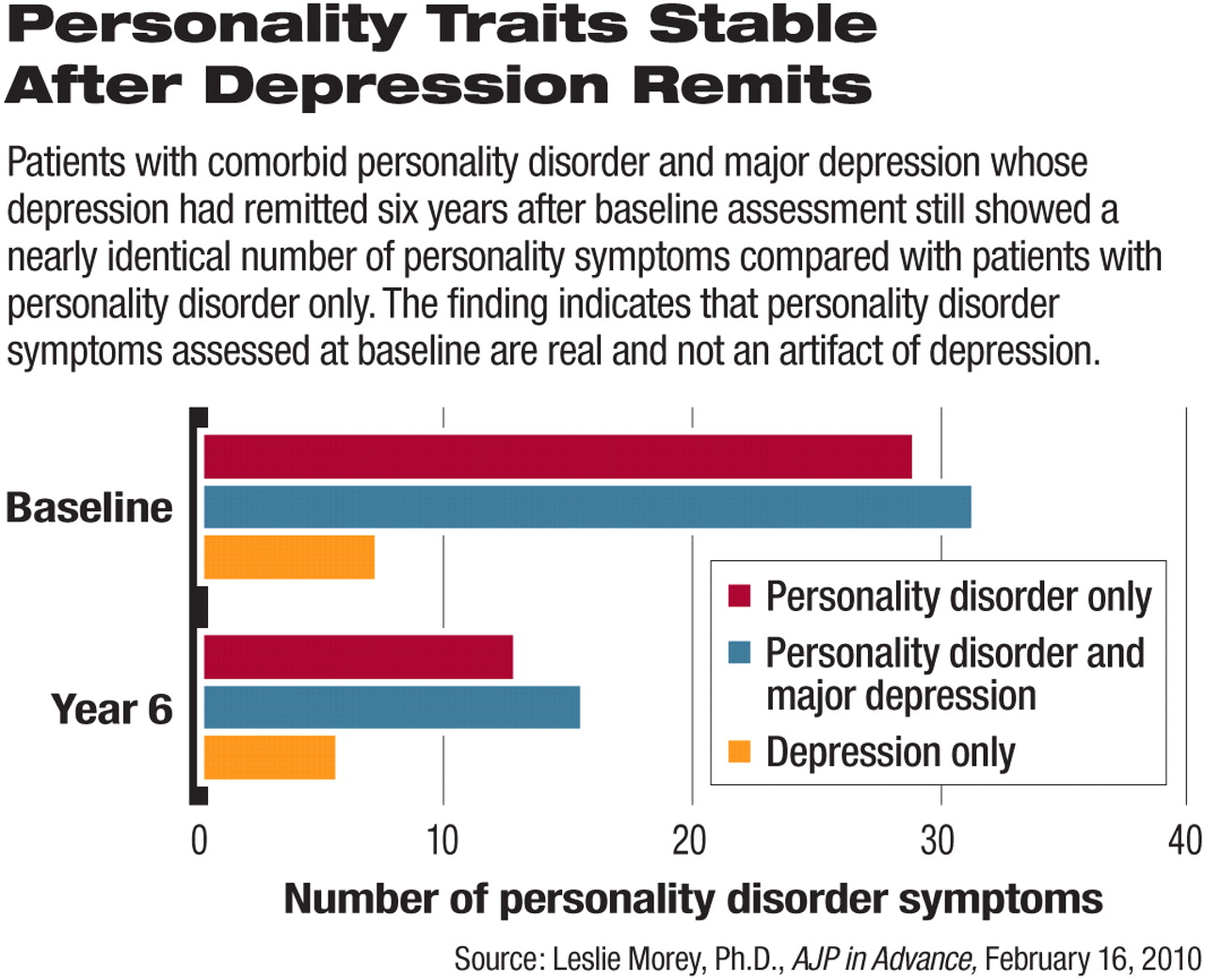

Not surprisingly, both personality disorder groups—those with and without depression—demonstrated significantly more features of personality disorder than the “depression-only group” at six-year follow-up.

More remarkably, even those comorbid patients whose depression had remitted at six years still showed a nearly identical number of personality disorder symptoms compared with the “pure personality disorder only” group (see chart).

What this indicates, Morey told Psychiatric News, is that personality disorder traits assessed at baseline should be regarded as true personality pathology.

The findings confirm the stability of personality traits over time and the generally difficult prognosis for patients who have a personality disorder with or without depression. Yet Morey suggested a possible silver lining—just as the personality disorder symptoms seen on evaluation do not appear on the basis of this study to be an artifact of depression, so too any improvement that comorbid patients make with regard to personality symptoms over time should be regarded as real and not a byproduct of treating depression.

“If clinicians are treating comorbid patients for some period of time and they do seem to be getting better with regard to personality, that is not probably a byproduct of their depression treatment, but an indication that they are making some headway in terms of their personality disorder,” he said.

Morey's advice to clinicians? “Trust what you are hearing from the patient about personality pathology regardless of depression, because it is very likely real.”

An abstract of “The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: Development, Aims, Design, and Sample Characteristics” is posted at <www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11213788>. “State Effects of Major Depression on the Assessment of Personality and Personality Disorders” can be accessed at <http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/pap.dtl>.