Depression Screening Can't Get Much Briefer Than This

Abstract

Brevity may not only be the soul of wit, it may also be the key to identifying a pediatrician's patients who may be struggling with depression. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force last year recommended screening for depression among adolescents, but how can busy primary care clinicians shoehorn yet another screen into a typical office visit?

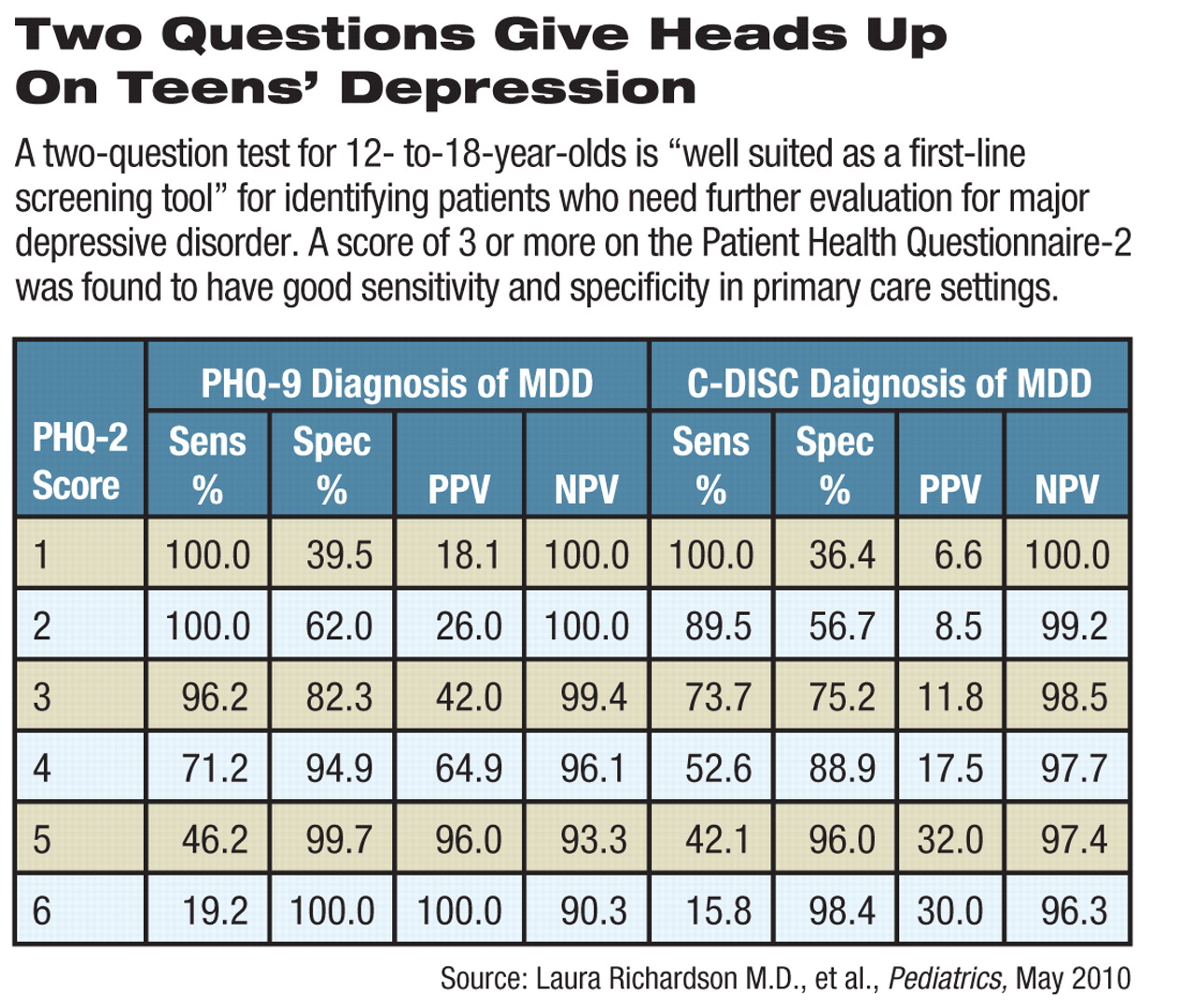

One way is to make the screening instrument as short as possible. Researchers have found that two inquiries, drawn from the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9, can serve as a useful first-pass signal to decide which young people need further evaluation (see See also: Brief Screening Tool Could Be Used to Assess Suicide Risk).

The PHQ-2 was “promising as a first step” and had “good sensitivity and specificity for detecting major depression,” they wrote in the May Pediatrics.

“The PHQ-2 is well-suited as a first-line screening tool for depression because it is brief, easy to score, and available without cost,” wrote Laura Richardson, M.D., M.P.H., an associate professor of adolescent medicine and an adjunct associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington; Wayne Katon, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at that university; and colleagues.

Studies like this are encouraging to many of those working at the intersection of pediatrics and psychiatry.

“The more research on primary care screens, the better,” said Rachel Zuckerbrot, M.D., an assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University. Zuckerbrot is board certified in pediatrics, child and adolescent psychiatry, and general psychiatry. She was the lead author of the American Academy of Pediatrics' 2007 guideline for identifying and assessing adolescent depression in primary care settings.

The new study carries added weight because the researchers validated the results they obtained with the PHQ-2 by comparing them with scores on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-IV (DISC-IV), considered the “gold standard” for diagnosing depression in young people, said Zuckerbrot.

She and the authors acknowledged, however, that the PHQ-2 focuses only on major depression and may miss milder forms of depression or irritability, a DSM-IV criterion for depression in adolescents but not in adults.

A question about suicidality on the PHQ-9 is not part of the PHQ-2, so the 20 percent of youth with suicidal ideation could be missed by the two-question screener, the researchers noted. They recommend adding a question about suicidality to the PHQ-2 to compensate.

The test of the PHQ-2 was part of the Adolescent Health Study jointly run by the University of Washington and the Group Health Research Institute in Seattle.

The researchers began by randomly selecting 4,000 adolescents aged 13 to 17 who had been seen at a Group Health site in the previous year.

Of those, 2,291 (61 percent) completed a brief 10-item mail-in survey that included the PHQ-2 questions on depressed mood and/or lack of pleasure in usual activities in the previous two weeks. Respondents indicate severity on a 0-3 scale for each question.

A score of 3 (out of 6) or higher in adults has been shown to have good specificity and sensitivity for major depression.

Most youths with a PHQ-2 score of 3 or higher and an age- and gender-matched control group completed a more extensive phone interview that included the PHQ-9, the DISC-IV, the Columbia Impairment Scale, the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders, and the Brief Pediatric Symptom Checklist.

In all, 242 teens who screened positive and 202 controls, and the parents of both groups, completed the study.

The false negative rate was 26 percent, and the false positive rate was about 25 percent. However, 76 percent of the false-positive group had some other cause for concern, such as intermediate depression, externalizing symptoms, anxiety, or depression in the prior year although not in the preceding two weeks. Follow-up with those patients would presumably identify those symptoms.

Follow-up to a positive screen depends on a number of factors at the patient, provider, and system levels, said Zuckerbrot. “How comfortable is the patient in primary care versus specialty mental health care?” she said. “How comfortable is the primary care doctor in treating depression? And what are the constraints on services caused by geography, insurance, or ability to schedule an appointment with a specialist.”

The study received support from the Group Health Community Foundation Child and Adolescent Grant Program, the University of Washington Royalty Research Fund, a Seattle Children's Hospital Steering Committee Award, and an award for Richardson from the National Institute of Mental Health.

“Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a Brief Screen for Detecting Major Depression Among Adolescents” can be accessed at <http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/vol125/issue5> by clicking on the study title.