Stigma Proves Hard to Eradicate Despite Multiple Advances

Abstract

In the 1990s the U.S. Congress, through House Joint Resolution 174, declared the decade beginning on January 1, 1990, as the Decade of the Brain, a campaign to enhance public awareness of the benefits to be derived from brain research.

In conjunction with that resolution, in 1999 U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher, M.D., issued a landmark report on mental health. In it, he emphasized that the stigma associated with mental illness was a “primary barrier” that often prevents treatment and hinders recovery. Hence, it was thought that if conditions of the mind could be better explained in part by a scientific “cause-and-effect” relationship, then the stigma associated with mental illness would wane.

Despite these efforts, a study published in the November 2010 American Journal of Psychiatry found that much stigma remains. In fact, when researchers compared 1996 and 2006 General Social Survey (GSS) data, stigma had increased in some areas.

Researchers found that the percentage of respondents indicating that they would be unwilling to have a person with schizophrenia as a neighbor significantly increased from 34 percent to 45 percent during that decade. This same unwillingness was found to have decreased from 44 percent to 39 percent regarding individuals with alcohol dependence and from 23 percent to 20 percent in those with depression during that time period.

The percentage reporting that they would be unwilling to have an individual with alcohol dependence marry into their family rose significantly from 70 percent to 79 percent. There was a smaller, though not significant, increase for those with schizophrenia—from 65 percent to 69 percent. For depression, there was a slight decrease from 57 percent to 53 percent.

The researchers also found in 2006 that most survey respondents said that they would expect that a person with schizophrenia or alcohol dependence (60 percent and 67 percent, respectively) would “more likely be violent toward others.” In contrast, this belief was found to be the case in only 32 percent of persons who responded to vignettes describing individuals with depression.

The study, by Bernice Pescosolido, Ph.D., and colleagues, analyzed data from 1,956 respondents from two modules within the GSS, which were administered in 1996 and 2006. The GSS is funded by the Sociology Program of the National Science Foundation and administered by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC). The NORC, the oldest national survey research organization, is affiliated with the University of Chicago.

In both surveys, individuals were queried to obtain information that would help researchers gauge the public's knowledge about three mental health conditions—alcohol dependence, major depression, and schizophrenia.

Pescosolido, director of the Indiana Consortium for Mental Health Services Research and a distinguished professor of sociology at Indiana University, outlined the key questions surrounding beliefs about and attitudes toward individuals with mental illness in an interview with Psychiatric News.

She explained that the overall goal of the study was to see whether major changes in U.S. society that took place in many realms in the decade beginning in 1996 also translated into a major shift away from stigmatizing mental illness and those who suffer from it.

Questions in each survey focused on respondents' understanding of the causes of mental illness, their openness to treatment, and attitudes that indicated stigma toward mental illness. In trying to measure stigma, questions asking about issues such as social distance and perception of dangerousness of an individual suffering from mental illness were presented in a case-vignette format.

In comparing the surveys, the main goal of the research, Pescosolido noted, was to see if the multiple public-education and other efforts actually changed “the prejudice associated with mental illness.”

“Because stigma can be either the prejudice or the discrimination,” she said, “the study really focused on the cultural and attitudinal beliefs of individuals,” not whether they would openly discriminate against someone with mental illness.

The authors reported that stigma, which can be a “primary barrier” to an individual's treatment and recovery, has influenced subsequent policy and reform efforts to increase the rates of service use among individuals with mental illness as well as the numbers of mental health care providers. Despite these efforts, much discrimination and many misconceptions regarding individuals affected by psychiatric illness still remain.

Public knowledge and understanding of mental illness and individuals' attitudes toward someone with mental illness were measured by questions in three broad areas: their understanding of the cause of mental illness; endorsement of treatment by a health care facility, provider, or prescription medicine; and their acceptance of someone with a mental illness.

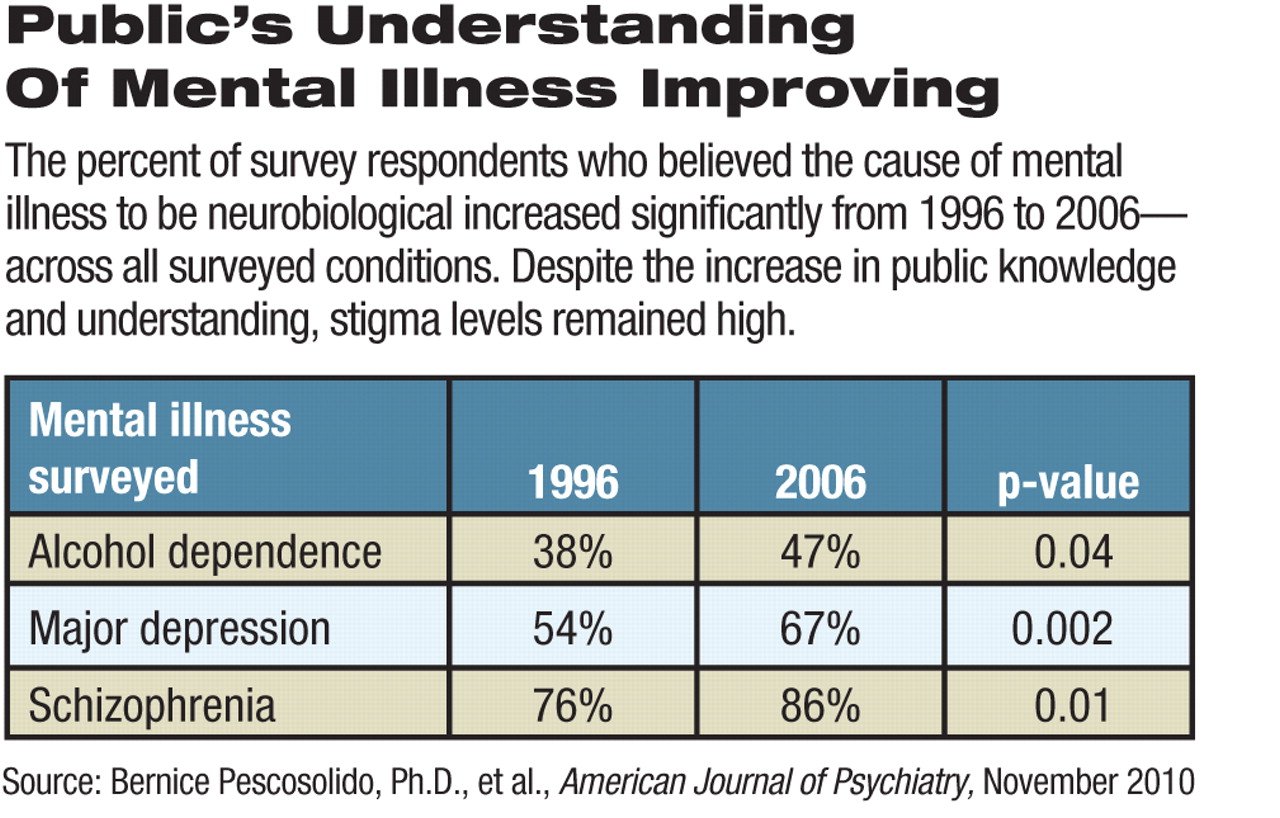

The researchers also found that, from 1996 to 2006, the public's awareness that mental illness may be due to a neurobiological cause increased across the three conditions surveyed, with increases ranging from 9 percent to 13 percent.

In addition to attitudes, Pescosolido stated that the study results also indicated that over the years, individuals' beliefs about mental illness have “changed in dramatic ways.”

Not only have “people's attitudes changed about the underlying causes, they have changed about whether people should go for treatment. So, those are all good things, but it didn't translate into the reduction of stigma, which was what the hope had been,” she said.

As the study reported, the percentage of individuals responding that they believe an individual with a mental illness should seek treatment with a prescription medication for all three conditions—alcohol dependence, depression, and schizophrenia—increased significantly, ranging from an increase of 40 percent to 71 percent in 1996, up to 53 percent to 86 percent in 2006. The authors also found that the percentage of survey respondents indicating that they would recommend that someone with a mental illness seek the treatment of a physician has increased significantly as well, by as much as 15 percent from 1996 to 2006.

Also, the study reported that for individuals suffering from schizophrenia, public support for hospitalization increased significantly from 53 percent to 66 percent over the 10-year period.

In the issue's accompanying editorial section, Howard Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., agreed that “we may not have eliminated social stigmatization of symptomatic individuals with mental illness, but improved treatment has helped many of them to make their symptoms and dysfunction less visible and less problematic.” Goldman, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, is the editor of the APA journal Psychiatric Services.

Pescosolido expressed this view in regard to neuroscience's “incredible” contribution in “terms of cure” for mental illness. The study's primary focus was to bring to light to mental illness as “a generalizable concept that everyone has something that makes them different. . . . We need to understand and accept [that] difference,” Pescosolido told Psychiatric News.

In moving forward, efforts to reduce stigma may not necessarily focus on the public's understanding of the causes of mental illness, since this task is best left to researchers, said Pescosolido. She suggested instead having public efforts “focus on issues of competence, social inclusion, and full citizenship” for those with mental illness while researchers in neuroscience contribute in terms of developing treatments for mental illness. Effective treatments will help reduce the stigma associated with mental illness, said Pescosolido.

An abstract of “A Disease Like Any Other? A Decade of Change in Public Reactions to Schizophrenia, Depression, and Alcohol Dependence” is posted at <http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/167/11/1321>.