Risk Factors for Suicide in Veterans Become Clearer

Abstract

Veterans commit suicide at rates higher than the general population, but new studies point to risk factors appearing in the months and years before they die that may help guide prevention efforts.

Suicide among U.S. veterans is a long-standing problem. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has estimated that as many as 5,000 veterans kill themselves each year, accounting for 1 in 6 of the 30,000 annual suicides in the United States.

Those deaths come despite a variety of prevention efforts by the VA. Two recent studies looked at veterans' psychiatric status and contacts with the VA health system in the months and years before they committed suicide. Other studies reported the effects of mental health status and employment among veterans.

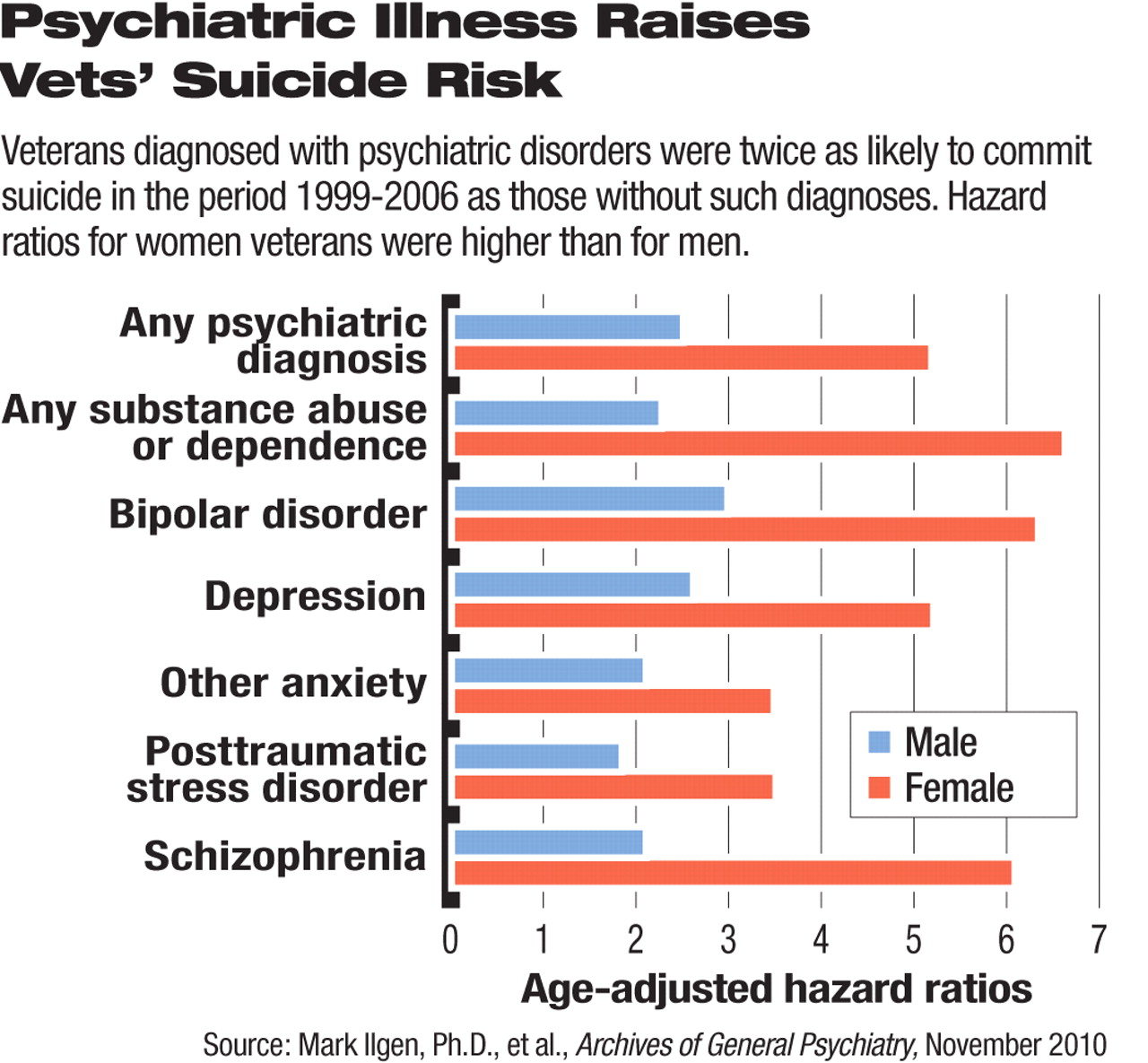

The relationship between psychiatric diagnoses and risk of suicide in VA patients becomes increasingly complicated when a large study population reveals patterns of risk, according to a study by Mark Ilgen, Ph.D., and colleagues published in the November 2010 Archives of General Psychiatry. Ilgen is an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan Medical School and a research investigator at the Department of Veterans Affairs' National Serious Mental Illness Treatment Research and Evaluation Center in Ann Arbor, Mich.

The researchers looked at records of all patients who used veterans' health services in 1999 and who were alive as of October 1, 2000—a total of 3,291,891 people. About 10 percent of that number were women.

Of the total population, 7,684 (0.23 percent) died by suicide as of October 2006 (7,426 men and 258 women). About 47 percent of those veterans had a psychiatric diagnosis in 1998 or 1999, compared with 26 percent of VA patients in general. Having a psychiatric disorder doubled the rate of suicide in the following seven years.

“In all likelihood, many individuals with psychiatric disorders who were at risk for suicide were not identified by the treatment system ... owing to stigma,” Ilgen and colleagues suggested in the article.

Strong Link to Bipolar Disorder Found

Bipolar disorder had the strongest association with suicide in this cohort, involved in only 9 percent of deaths but at a rate triple the overall rate of suicide. Clinicians might increase their focus on patients with bipolar disorder, given that heightened risk, the researchers noted.

The risk of suicide associated with a psychiatric diagnosis was higher among women than men, although only 3.4 percent of the patients in the study who died by suicide were women.

Recording differences in risk factors between men and women was a strength of the study, said Eve Moscicki, Sc.D., M.P.H., director of the Practice Research Network at the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education, who has studied risk factors for suicide. “Too often, men and women are lumped together, but we see different patterns of risk when they are separated.”

After bipolar disorder, the risk of suicide in men was greatest, in order, for those with depression, substance use disorders, schizophrenia, other anxiety disorders, and PTSD.

Among the 258 women who committed suicide during the study period, substance use disorders led the list of risk factors, followed by bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, depression, PTSD, and other anxiety disorders.

All values were statistically significant, but confidence intervals for women were wider because of their smaller absolute numbers.

Suicide among female veterans is often overlooked, said psychiatrist Bentson McFarland, M.D., Ph.D., of Oregon Health and Science University, and Mark Kaplan, Dr.P.H., and Nathalie Huguet, Ph.D., of the School of Community Health at Portland State University.

In a separate study based on data from the 16 states in the National Violent Death Reporting System, published in the December 2010 Psychiatric Services, they found that women with a history of military service were more likely to complete suicide than women who had not been in the armed forces.

The same authors reported three years ago that compared with nonveterans in the general population, veterans were twice as likely to die of suicide. They have also suggested that veterans' familiarity with firearms may contribute to that difference.

Was There Contact With VA System?

Another study, also published in the December 2010 Psychiatric Services, of 112 Oregon veterans who committed suicide, found that more than half had at least one health care contact with the Portland Veterans Affairs Medical Center in the 30 days before they died.

Lauren Denneson, Ph.D., and colleagues from that medical center studied 112 suicides by veterans (108 among men) from 2000 to 2005. All had some contact with the VA health system in the year before they died.

The researchers compared Oregon's violent-death data with the VA database to identify the 112 veterans, then reviewed the veterans' patient records. They looked to see if a VA clinician had assessed the patient for depression, PTSD, a substance use disorder, or suicidal ideation. Anything from a formal screening to a note in the medical record counted as an assessment.

Of the 112 veterans, 71 were seen for primary care visits during the year and 54 had mental health visits. Also, 62 veterans had at least one emergency department contact.

Digging into the numbers produced some potentially troubling insights. A total of 61 veterans had at least one contact with the VAMC in the 30 days before they died and 23 had a mental health contact. Six veterans endorsed suicidal ideation during this period and received additional suicide-risk assessment before they died.

During the year preceding death, 46 patients were assessed for suicidal ideation, although three-quarters of them denied having such thoughts.

Both primary care and mental health clinicians have opportunities to discuss mental health issues and suicidality with patients, but may not always do so, said the authors.

“[T]here are often few clinical indicators to trigger discussion of suicide risk with patients,” they wrote. “Unfortunately, we also found little evidence to suggest that inquiring about suicide will successfully identify the veterans most at risk of suicide.”

The VA health system has increased its suicide-prevention efforts since 2005, Denneson and colleagues pointed out. “However, we note that because many veterans in our study denied suicidal ideation, implementation of formal screening processes would likely have had limited impact.”

Perhaps more research into better ways of eliciting and communicating suicidal thoughts would help, they said.

The new studies support much previous research that psychiatric diagnoses are major risk factors for suicide, said Moscicki.

“Both of these studies highlight the extreme difficulty of predicting imminent death,” she said. “They send a strong message that we need a better system of identifying, diagnosing, and treating veterans with psychiatric disorders.”

Finally, other studies published in the same issue of Psychiatric Services found that veterans with bipolar disorder, PTSD, schizophrenia, or a substance use disorder were more likely to be unemployed, disabled, or retired than in the work force, and psychiatric disorders were associated with productivity losses among those who were working.

The cluster of articles in Psychiatric Services reflects increasing research on psychiatric issues in military and veteran populations, said Howard Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and editor of the journal.

“It should not be surprising, but we rediscover in every generation what a traumatic event war is,” said Goldman in an interview with Psychiatric News.

“Suicide Risk Assessment and Content of VA Health Care Contacts Before Suicide Completion by Veterans in Oregon” is posted at <http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/61/12/1192>.