Intelligence, Bipolar Disorder: What’s Behind the Link?

Abstract

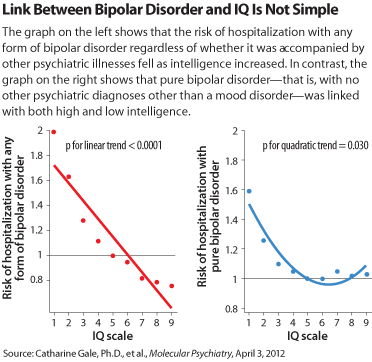

A prospective study of more than a million Swedish men—in which their intelligence was measured during their military conscription with verbal, logical, spatial, and technical subtests—has found a highly significant link between high intelligence and hospitalization for bipolar disorder during the subsequent 23 years.

However, when the researchers restricted their analyses to men with bipolar disorder and no other psychiatric diagnoses other than a mood disorder, they found a significant link between hospitalization for bipolar disorder and both high and low intelligence levels.

The researchers do not yet have solid explanations for these apparently conflicting results.

However, regarding the link between bipolar disorder and high intelligence, lead researcher Catharine Gale, Ph.D., a reader in epidemiology at the University of Southampton in England, suggested in an interview with Psychiatric News that it is “consistent with anecdotal and biographical reports linking high intelligence or great creativity with bipolar disorder. …”

And as for the relationship between bipolar disorder and low intelligence level, Gale said, “We know from previous research we have done in this cohort of men that lower intelligence is associated with an increased risk of a wide range of mental disorders and of having more comorbid mental disorders. So it is entirely consistent with this that lower intelligence was associated in this study with an increased risk of bipolar disorder. …”

Nonetheless, another study finding baffled Gale and her colleagues, she admitted. “When we examined the relationship between performance on the IQ subtests and … bipolar disorder …, we found that both high and low verbal ability, and, to a lesser extent, high and low technical ability were associated with increased risk. But there was no increased risk among men with high or low spatial or logical ability. This surprised us because, in general, people who perform well on one subtest tend to perform well on the others.”

These results probably do not have clinical implications for psychiatrists, Gale added, since “IQ is not a good predictor of whether someone will need to be hospitalized with bipolar disorder. On the other hand, our findings are likely to be of interest to those who are researching the etiology of bipolar disorder.”

The study cohort consisted of 1,049,607 subjects, 3,174 of whom were hospitalized for bipolar disorder; of the hospitalized subjects, 1,079 (34 percent) were hospitalized for symptoms of bipolar disorder without any comorbid psychiatric illness.

The study results were published April 3 online in Molecular Psychiatry. The study was funded by the U.K. Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research, and several other governmental organizations.

An abstract of “Is Bipolar Disorder More Common in Highly Intelligent People? A Cohort Study of a Million Men” is posted at www.nature.com/mp/journal/vaop/ncurrent/abs/mp201226a.html.