Polypharmacy: Too Much Of a Good Thing?

More and more clinicians today find themselves writing prescriptions for more than one antipsychotic medication to an individual patient. Yet, to date, little if any evidence has been published in the major peer-reviewed medical journals citing any clear benefit to antipsychotic polypharmacy. Antipsychotic polypharmacy may be well on its way to becoming standard psychiatric practice for some clinicians—several recent studies have indicated nearly half of all patients on antipsychotics are taking more than one drug.

“With the newer agents, you very often end up using multiple antipsychotics,” said Franca Centorrino, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and McLean Hospital. “We try to back up what we are doing in our clinical practices, so we look to the literature. And we find nothing there. Our clinical experience, of course, is biased. We try anything and everything to help the patient improve. [If the patient does improve,] you don’t really know if it was something unique to that patient or if it was something inherent in those multiple medications.”

Centorrino and her colleagues at McLean carried out a retrospective case-control study of patients admitted to their facility for a psychotic disorder during three months in 1998. They compared numerous aspects of treatment and its outcomes in patients being treated with antipsychotic polypharmacy with those being treated with monotherapy.

The team’s report appeared in the April American Journal of Psychiatry. The research was funded by grants from the Bruce J. Anderson Foundation and the McLean Private Donors Neuropsychopharmacology Research Fund.

Significant Differences—or Not?

A total of 140 inpatients in 70 matched pairs were studied. Each polypharmacy patient was matched to a monotherapy patient for comparison, based upon specific diagnostic category and clinical severity at admission to McLean. Baseline assessments included the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale, and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS—total, positive, and negative subscales). Pairs were also matched for gender, age, age at onset of psychotic illness, number of years of psychotic illness, and number of hospitalizations for psychotic illness.

Of all the factors the team examined in the baseline matching, only patient age at onset differed in the two groups. Those admitted while receiving antipsychotic polypharmacy were on average 4.2 years younger when their illness began than those who were admitted while receiving monotherapy.

Centorrino told Psychiatric News that this was an interesting finding. It might be plausible, she said, that those admitted on polypharmacy were actually more ill, although their assessment scores did not indicate it. Some studies have found that patients whose psychotic illness begins at an earlier age have a more difficult clinical course and a generally worse prognosis than those whose illness starts at a later age.

Thirteen antipsychotic drugs were prescribed to the 140 patients. The most common was olanzapine (46.4 percent of all patients), followed by quetiapine (33.6 percent), risperidone (19.3 percent), haloperidol (16.4 percent), perphenazine (16.4 percent), and clozapine (6.4 percent). Less than 5 percent of patients were on thioridazine, chlorpromazine, fluphenazine, thiothixene, loxapine, promethazine, or trifluoperazine.

(This study was completed before the approval of the newest antipsychotics, ziprasidone and aripiprazole.)

Most patients were prescribed at least one second-generation antipsychotic (88.6 percent), and the most frequently combined medications were olanzapine with haloperidol, olanzapine with quetiapine, and olanzapine with risperidone.

Many Questions, Few Answers

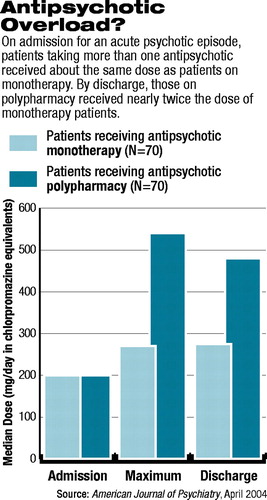

Although initial doses of antipsychotic (in mgs a day as chlorpromazine equivalents) were similar in both groups at baseline, the final doses at discharge were dramatically different. Those receiving polypharmacy were on doses 78 percent higher than those on monotherapy (see chart).

Although initial doses of antipsychotic (in mgs a day as chlorpromazine equivalents) were similar in both groups at baseline, the final doses at discharge were dramatically different. Those receiving polypharmacy were on doses 78 percent higher than those on monotherapy (see chart).

Despite those staggering differences in dosage, Centorrino said, those on polypharmacy did not improve to a greater extent than those on monotherapy. In fact, Centorrino added, “we thought we would see that not only patients on polypharmacy would do better, but they would be discharged quicker.”

Only 11 percent separated the two groups on GAF, CGI, and PANSS scores at discharge, but the differences weren’t statistically significant. To the researchers’ surprise, patients on polypharmacy were hospitalized on average 8.5 days (55 percent) longer than those on monotherapy. In addition, patients on polypharmacy experienced 56 percent more adverse events than those on monotherapy.

The clinical implications of the findings could certainly be significant. Yet, the economic links to polypharmacy are certain—increased pharmacy expenditures for more medications and increased inpatient hospitalization, all leading to higher potential costs for patients on polypharmacy (see Original article: page 20).

Centorrino wondered whether patients who were on polypharmacy were hospitalized for longer periods due to those adverse events or whether they actually were sicker in the long term and “their rate of response to therapy was slower.”

A significant limitation of the study, she said, was that “we were not able to capture how patients were doing over time throughout their hospitalization. That would have given us more answers—to be able to see a rate of improvement over time compared between the two groups.”

As it is, the data reflect only baseline assessments at admission and discharge assessments, with an average length of stay for hospitalization.

“Our study really offers more questions than answers, but clearly the data question the basis for antipsychotic polypharmacy,” Centorrino concluded. She and her colleagues call for more research, preferably as a prospective, randomized study comparing patients on antipsychotic monotherapy with patients on polypharmacy.

This study documents “that combining antipsychotic drugs is prevalent, is used in treating patients who may be more severely ill or less responsive to a single agent, and yields few or questionable benefits,” summed up Jeffrey Lieberman, M.D., a professor of psychiatry, neurology, and radiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the principal investigator of the National Institute of Mental Health’s Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study. That study looks at comparative effectiveness of most of the newer antipsychotics.

While Lieberman agreed that it is useful to be able to document what had been “prevailing clinical impressions,” controlled clinical trials are needed to answer the question of whether antipsychotic polypharmacy is appropriate and, if so, under what circumstances.

The study, “Multiple Versus Single Antipsychotic Agents for Hospitalized Psychiatric Patients: Case-Control Study of Risks Versus Benefits,” is posted online at http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/abstract/161/4/700. ▪

Am J Psychiatry 2004 161 700