More Than Words: Automated Speech Analysis May Offer Clinical Insight

Abstract

Subtle changes in semantics and syntax can differentiate which individuals are at greatest risk of developing psychosis, offering a powerful and objective diagnostic tool.

More and more, computer algorithms are being used by humans to assist them in filtering language—educators use them to quickly identify plagiarized text, human resources use them to screen resumes, and advertisers tailor their pitches to the content of our daily emails.

Using computers to analyze language could also prove valuable in the psychiatric arena, where language is an essential part of the evaluation and treatment process.

“Speech is an incredibly complex and rich form of data in terms of clinical information,” said Gillinder Bedi, D.Psych., an assistant professor of clinical psychology at Columbia University. “In addition to the information someone is telling you, facets such as inflection, acoustics, rate of speech, or pauses carry substantial information that we interpret as listeners.”

Subtle changes in a person’s speech can also serve as an early indication of a problem in the brain, Bedi said, including both acute conditions such as alcohol intoxication and chronic disorders such as dementia or psychosis.

According to Bedi, automated speech processing software might be able to identify changes in speech at their earliest stages, complementing a clinician’s subjective insight with an objective analysis and leading to more accurate diagnoses.

In a recent paper, Bedi and Cheryl Corcoran, M.D., an assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia, along with colleagues at Columbia, IBM’s T.J. Watson Research Center, Brazil, and Argentina described how automated speech analysis can be used to identify individuals who will go on to develop psychosis.

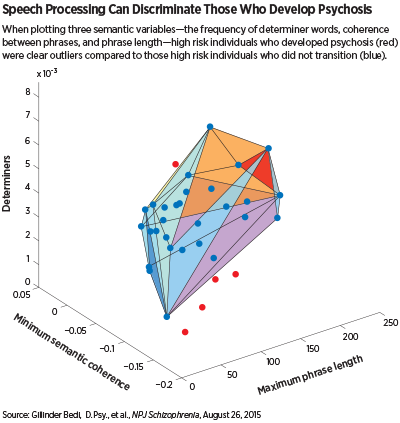

For the study, which was published in NPJ Schizophrenia, the researchers used an algorithm to evaluate transcripts from interviews with 34 youth considered to be at risk for schizophrenia (five of whom would eventually develop a psychotic episode), conducted every three months for up to 2.5 years. Using automated analysis, the transcripts from the interviews were analyzed for their average phrase length, the frequency of determiner words such as “that” and “which,” and the semantic coherence.

As Corcoran explained, semantic coherence refers to a narrative flow—the extent to which subsequent phrases or sentences in speech are related to one another in terms of meaning. “Automated speech analyses estimate semantic coherence by assigning meaning to every word in the language—much as humans do—by considering prior experience with the word in many different contexts,” she said.

According to Corcoran, in automated analysis, every word is assigned a semantic value based on its co-occurrence with every other word in the language; the value is represented as a directional vector. In turn, the semantic vector for a sentence is the average or sum of all the semantic vectors of the constituent words; these sentence vectors can be lined up to see if meaning flows naturally from one sentence to the next.

If someone is speaking coherently on a topic, then the phrase vectors will line up, Corcoran, senior author on the study, told Psychiatric News. However, if the vectors of successive phrases point in very different directions, this indicates semantic incoherence.

When each participant was plotted on a 3D graph based on his or her scores for each speech component, the researchers found that all five individuals who developed psychosis demonstrated speech patterns that were clear outliers from the other 29 youth.

“Now discrimination is not the same as prediction, but this does show there are distinct semantic differences in someone who will develop psychosis up to two years before it happens,” said Bedi. “Our goal now is to predict, at the level of the individual, who will go on to develop psychosis and who will not.”

Corcoran already has data from a second cohort of at-risk individuals, as well as healthy participants and people who have experienced psychosis. She has applied for funding to carry out the analysis.

“Our 100 percent record will not persist, but if we can get an algorithm that predicts with 90 or even 80 percent accuracy the people most likely to develop psychosis, it would still outperform the current clinical ratings,” Corcoran said.

She is also exploring whether the technology can detect changes in speech patterns in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a risk state that precedes Alzheimer’s disease.

“In both Alzheimer’s and MCI, there is a decrease in semantic fluency, which is the generation of different words that have to do with a single topic. This can be easily assayed with automated speech analysis,” Corcoran said.

Bedi, meanwhile, is exploring whether these methods can be applied to identify drug and alcohol abuse. Her first efforts, published last year in Neuropsychopharmacology, compared the speech patterns of people on MDMA (ecstasy) or methamphetamine with placebo. She found that the semantics of speech changed depending on drug condition, and the analysis program could discriminate the drugs taken by the participants with over 80 percent accuracy.

More broadly, both researchers believe that the results from automated speech analysis studies should encourage more collaboration between psychiatrists and computer scientists. Psychiatry has much to gain from advancements in computing power used in other areas of science and industry, they suggested.

The research by Corcoran and Bedi is supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Center for Advancing Translational Science, and New York State Office of Mental Hygiene. ■