The Rise and Demise of America’s Psychiatric Hospitals: a Tale of Dollars Trumping Decency

Abstract

This is the first of a two-part series.

The bedrock of American inpatient psychiatry was not the public psychiatric institutions alone as many believe, but rather a mix of public and private institutions. The 13 founding members of the American Psychiatric Association (first called the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane) came from about an even mix of state asylums and private facilities. Many states purchased beds at private institutions before deciding it would be more cost-effective to build and staff their own public institutions. Some resisted the shift from private to public. After decades of supporting the Vermont Asylum for the Insane in Brattleboro (Brattleboro Retreat after 1898) through payments for state patients, overcrowding there finally forced Vermont to build its own state hospital in 1890 in Waterbury.

Despite being initially called lunatic asylums, these institutions were not conceived of as places for shelter and support only, but rather as places to treat and cure mental illness. They were carefully situated and constructed to be therapeutic environments (there were salubrious climate considerations). The superintendents reported high “cure” rates. It was these favorable statistics that were the backbone of Dorothea Dix’s message to state legislatures. Basically, the options were for the state to pay to care for individuals for a lifetime in a goal (jail) or almshouse or admit them to a public hospital (which the state would build), treat them, cure them, and send them back out to their home communities to get jobs and rejoin the ranks of tax payers. Dix’s message was hard to argue with: do what’s right and build a public psychiatric hospital and save public funds at the same time.

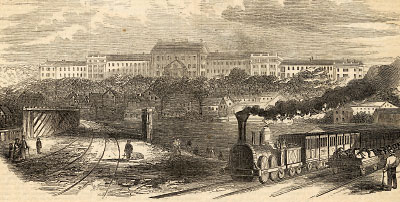

In many 19th century psychiatric hospitals, work was part of some patients’ therapy and often helped support the institution. Pictured is New York’s Utica Psychiatric Hospital.

The early asylum superintendents and their very small workforces had therapeutic approaches, such as moral treatment, supplemented by bloodletting, purgatives, and cathartics. Patients labored to keep the asylum functioning. Some were employed in a manner we might today call peer supports. Pliny Earle, superintendent of the Northampton (Mass.) Lunatic Asylum, kept the names of the patients who had keys on the last pages of his appointment book.

New presentations of symptoms ascribed to insanity were viewed as acute diseases, and when one was no longer symptomatic, one was considered cured. Thus, a person could present to the asylum three times in a year and be cured three times. Since asylum statistics compared only the outcomes of discharges, cure rates could be quite high. For example, if 200 patients were discharged and 140 were asymptomatic, the cure rate was 70 percent. Pliny Earle, shortly after he retired as superintendent, published a book that put an end to the curability myth. By then, many states had built one or more asylums and had enlarged, or in a few cases replaced, some of them.

View of the Worcester Lunatic Asylum.

Psychiatric disorders and asylums could be used to address what some saw as political problems. In 1851, Samuel Cartwright, a prominent Louisiana physician who had studied under Benjamin Rush but was not a psychiatrist, identified two mental disorders peculiar to slaves: Drapetomia, or the disease causing blacks to run away, and Dysaethesia Aethiopica, or the condition that accounted for laziness among slaves. Such diagnoses, of course, were racist pathologizing of reasonable behavior.

In 1855, Edward Jarvis, a physician but also not a psychiatrist, found that the Irish in Massachusetts were disproportionately insane, as the state’s governor suggested he should. In the debate about how to address the problem—deportation or build another state hospital—insane asylum construction won out, and the state built an asylum in Northampton, about as far from Boston as the citizens of Massachusetts could imagine. When it opened, Irish patients from the other Massachusetts asylums were sent there. In an interesting footnote, Jarvis, the father of American biostatistics, in all likelihood knew that the Irish were disproportionately poor and the correlate with insanity was poverty, but that’s not what the governor had instructed him to find.

Dorothea Dix was instrumental in encouraging states to build and support public psychiatric hospitals. Her message to state legislatures was hard to argue with: do what’s right and save public funds at the same time.

The 19th century asylums became victims of their own advertised success. Once built, patients were admitted in numbers far greater than the facilities’ capacity. The asylums’ single-room design for patients became unsustainable. Wings began to be added. The longer-stay patients kept being relocated to the wing farthest from the main entrance, hence the origin of the expression “back ward.” While censuses grew relentlessly, the number of staff, never very many, did not increase proportionately, and providing treatment became harder. Moreover, the public institutions could not use remedies that were available to private facilities: when Luther Bell, superintendent of McLean Asylum and a founding member of APA, was faced with overcrowding, he did what any CEOs would do when demand exceeds supply—he raised the rates at McLean.

By 1890, three years after Dorothea Dix’s death, every state in the United States had at least one public psychiatric hospital. Worcester, Mass., had long replaced its first public hospital but at a different location as the city’s residents complained that with the growth of the city, the first hospital was too close to the population. “NIMBY” (“not in my backyard”) is not a new phenomenon. New private psychiatric hospitals were also opening. In 1891, Sheppard Asylum in Maryland (now Sheppard Pratt Health System) began admitting patients.

Jeffrey Geller, M.D., M.P.H., is a professor of psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts Medical School and a member of the APA Foundation Library and Archives Advisory Committee. Geller will become president-elect of APA at the end of APA’s Annual Meeting in May.

Economics has always directly impacted the functioning of public psychiatric hospitals with cost shifting among various payers having a crucial role. Local governments realized near the end of the 19th century that they could avoid the costs of caring for elderly residents in almshouses or county hospitals by redefining what was then termed “senility” as a psychiatric disorder and sending these men and women to state-supported asylums. These individuals, however, were not amenable to asylum treatment methods, and their numbers added to the overcrowding problem and inhibited states’ willingness to fund acceptable care.

It’s easy to see that at the end of the 19th century, the asylums were on their way to becoming overcrowded repositories for the states’ unwanted poor and debilitated citizens. ■

Purchase Tickets for 175th Anniversary Gala Today!

With a history spanning 175 years, APA has a lot to celebrate. Join your colleagues and friends for an evening of music, dancing, and good food at APA’s 175th Anniversary Gala. The celebration will be held at the city’s crown jewel, San Francisco City Hall on Monday, May 20, from 7 p.m. to 10 p.m.

Tickets for the event are $225 per person, with special pricing for APA/APAF fellows and resident-fellow members. Purchase your tickets at https://apafdn.org/gala or call (202) 559-3888. For more information, see page 11. For information about Annual Meeting registration, click here.