Special Report: Be Prepared to Address Technological Addictions in Psychiatric Practice

Abstract

In an ever-expanding high-tech environment, some individuals who are overly preoccupied with technology and online activity may need psychiatric help.

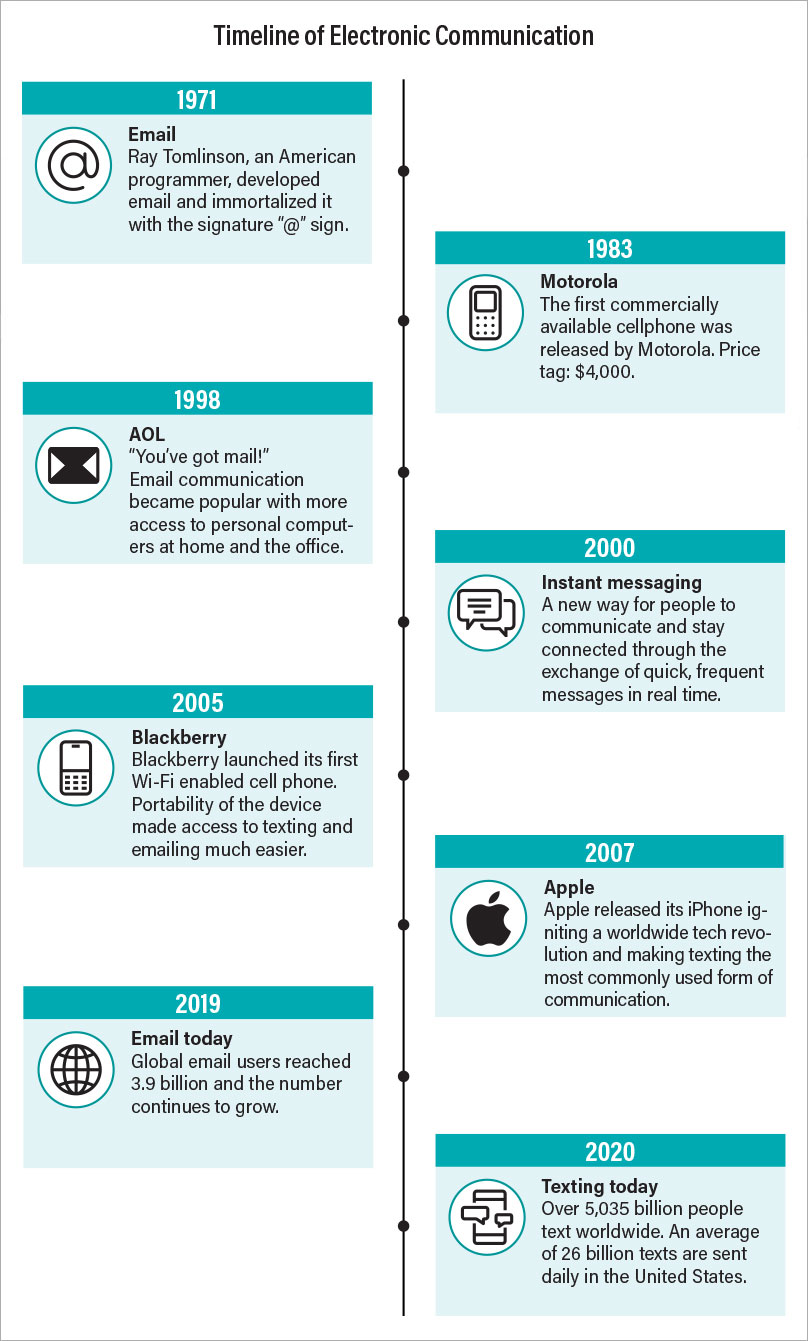

Though online technologies like interconnected computers and electronic messaging can trace their origins to the 1960s, the online world did not take off until the end of the 20th century with the advent of a public World Wide Web and the rise of the cellular phone. Since then, however, we have seen an explosion in online applications that have connected people across the globe in ways never imagined. Billions of text messages are sent across smartphones each day, keeping distant friends and family in touch, while consumers can find almost any product they need without leaving their house.

The benefits offered by online technologies have become more evident since the COVID-19 pandemic began, as offices, schools, and health care centers transitioned to virtual services to continue operating under socially restrictive guidelines. Though this “new normal” has been imperfect, the ability to work, learn, and socialize remotely has mitigated many of the adverse impacts of this pandemic.

But the seemingly endless bounty offered by online technology is not without risks. Just as happens with substances like alcohol or opioids, some people become so caught up in their virtual world that their real world—jobs, finances, relationships, physical health—begins to suffer. As smartphones and other modern devices become more and more integrated into all facets of life, understanding, identifying, and treating these technological addictions will become a significant aspect of psychiatric care.

Medical Illness vs. Societal Ill

When conceptualizing technology-related addictions, we limit our scope to the people who exhibit a true medical disorder. Most people can use technologies for extended periods without ill effect. Parents, teachers, and doctors may bemoan that today’s youth are spending too much time online, but in most cases the children do not develop clinical problems. And although there is a growing consensus that social media is decreasing our civility and increasing tribalization, negative online behaviors are not necessarily indicative of an underlying disorder. The question of how online technologies are influencing our wellness, happiness, and creativity is extremely relevant, but let us leave that discussion for another day and invite the sociologists, philosophers, and policymakers to join the conversation.

Cybersex: An All-Inclusive Term

Online Pornography

Online Dating

Sex Chats

Sex Webcams

Teledildonics

From a psychiatric perspective, we are primarily concerned with those individuals who continue to be preoccupied with a technology despite experiencing internal preoccupation and external consequences. Just as with substance use disorders, people with a genuine technological addiction can develop tolerance and require greater time or intensity in their behavior to achieve the same effect. People with a technological addiction also think obsessively about their behavior when not online, and they experience withdrawal symptoms if they are shut out from their technology of choice.

Only one technological addiction has been semi-officially recognized by APA as of DSM-5: internet gaming disorder is in Section III of our manual as a condition for further study. However, addiction specialists generally agree on seven major online behaviors of concern: internet gaming, online gambling, online shopping, cybersex, internet surfing, texting/emailing, and social media.

Technology’s Seven Discontents

Internet gaming disorder: Given its inclusion in the back pages of DSM-5 as well as in the most recent International Statistical Classification of Diseases (as gaming disorder), problematic gaming can be seen as the prototype disorder that can help professionals develop diagnostic criteria and treatment plans for other technological addictions. This disorder rose to prominence during the heyday of massive multiplayer online games like World of Warcraft, with stories of gamers losing themselves in their online world at the expense of real-world connections. Today, problematic gaming can occur on both high-performance computers and basic smartphones, as game developers have become more adept at keeping players in a psychological “flow state.” A game’s challenge rises concurrently with a player’s skill and experience, such that the player becomes neither bored nor anxious, encouraging (or rather forcing) longer play.

Internet gambling disorder: While gambling disorder is recognized in DSM-5, the internet has broadened the opportunities for problematic gambling immensely. In addition to virtual recreations of casinos and racetracks, online gambling can be found in a range of fantasy sports leagues and brokerage firms that let people engage in wild and speculative trading of stocks and other investments like cryptocurrencies. Some online sites have even prospered by offering casino-like games without any tangible payoff; this has led some experts to reconceptualize addictive gambling not as a rewards-based disorder, but an irresistible attraction to the thrill of risking something of value.

Online shopping disorder: This category includes traditional purchase shopping as well as auction shopping, which adds some of the thrill of gambling. As with gambling, problematic shopping was around in the brick-and-mortar days, but the online experience has exacerbated the risks by shrinking the path to purchase. This four-step model posits that consumers go through a period of awareness (there’s a new product out), consideration (that might be good for me), conversion (I’m going to the store this weekend to buy it), and evaluation (I like it and will tell my friends) with each purchase. With endless advertising, boundless product reviews, and time-limited flash sales, the internet has made this cycle near instantaneous. As with addictive substances (think tobacco, intravenous heroin, or alprazolam), the quicker the onset of action, the greater the addictiveness of the drug or the behavior.

Cybersex: Though internet pornography springs to mind when thinking about cybersex, this disorder also includes more active and social behaviors like adult webcams, sex chats, and even unhealthy online dating. The current frontier in this field is teledildonics, a form of virtual sex in which webcam viewers can remotely control sexual stimulation devices used by the host. As with shopping or gambling, sex addiction is not new, but online technologies have let people explore sexuality with far more accessibility, affordability, and anonymity than ever before, which may be of particular concern with younger individuals.

Internet surfing and infobesity: While people have joked that no one has yet found the end of the internet, the vast amount of online information can lead to a pair of related problems. The first is the classic journey of surfing from one webpage to the next via hyperlinks or search engines, as a user’s momentary interests distract from a prespecified task. Soon, people find they wasted hours of potential productivity going down online rabbit holes. On the other hand, people who stay focused on a task while online can find themselves experiencing information overload, or “infobesity.” In this proposed disorder, users find so much information on their topic of interest that they don’t know how to sort through it all and proceed, leading to a state of productive paralysis.

Texting/email addiction: Communication is an important component of human behavior, and it’s undeniable that texts and emails have become a preferred tool for keeping in touch with friends, family, and coworkers. In some instances, though, the time devoted to online chatting and the content of communication become unhealthy, with sexting and cyberbullying being two prominent examples.

Social media addiction: It may be appropriate to end the list with social media since this topic may have the fuzziest delineation between healthy and unhealthy use. Many people believe if social media apps like Facebook or Twitter disappeared altogether, the world would be much improved. As previously noted, however, debates on the repercussions of the social media era are somewhat beyond the scope of everyday clinical psychiatry. The relevant issue is whether patients are experiencing significant symptoms and consequences due to their social media use. As social media is still a rapidly evolving space, identifying addictive use is difficult, but one strong warning sign could be extended passive use of social media, where one is more voyeur than active participant. Another red flag may be related to FOMO, or the “fear of missing out” on the latest news developments or the fabulous lives of others, as a person’s driving factor in social media use.

Diagnostic Dilemmas: All for One or One for All?

In examining the above list, one can see that these (proposed) disorders have not arisen from the depths of the World Wide Web; most of these online behaviors have addictive reflections in the real world. Our professional great grandparents Emil Kraepelin and Eugene Bleuler, for example, described compulsive shopping disorder more than a century ago, while accounts of compulsive gambling or sex addiction are older still. Even some problematic elements of social media use, such as obsessive following of photos and videos from influencers, resemble the problems seen a generation ago among youth who obsessed over fashion magazines. Given these connections, some might wonder whether we need to establish a class of technological addictions; perhaps it is better to incorporate these problems into existing frameworks of behavioral addictions—for instance, making internet gambling disorder a subtype or specifier of gambling disorder.

But while the base behaviors are similar, conducting these behaviors through a digital intermediary can alter many fundamental aspects of the disorder. In gambling disorder, for instance, individuals are diagnosed who meet a minimum set of criteria over the previous 12-month span, reflecting that gambling episodes are often sporadic and not always financially ruinous. With online gambling, the same at-risk individual now has 24/7 access to casinos, and the symptoms for diagnosis of a disorder might emerge in a couple of months or even weeks. Likewise, many people engage in cybersex specifically to experience “online dissociation,” which makes the psychology of the disorder quite different from that of those who have real-world sexual dysfunction.

Another option floated by some professionals is to develop broad diagnostic criteria based on platforms, such as internet addiction or smartphone addiction. There is certainly a rationale for this. Consider online gaming: While the ability to maintain gamers in a “flow state” contributes to addictive gaming, developers also increasingly entice gamers with elements derived from gambling (loot boxes that offer prizes of varying rarity) and shopping (releasing a game for free but incorporating microtransactions to unlock bonuses or cosmetic upgrades) arenas. Likewise, many online gambling sites have taken to gamifying their experience (for instance, by enabling players to level up their casino avatar the more they play) or adding sexual elements to separate themselves from physical casinos.

However, individuals have different motivations and gratifications when conducting each of these online activities. While gambling can be seen as a thrill of risking something of value, shopping is done for the thrill of acquiring something of value. In addition, data suggest that certain demographics may be at elevated risk of different addictions. Online gaming addiction occurs more frequently in men, while social media addiction is more likely to afflict women; texting addiction is seen more often in young adults, while shopping addiction is more common in older adults. Understanding these differences will help professionals develop more robust screening tools and treatment strategies.

How Do I know If My Patient Is Addicted to Technology?

For classic substances of misuse, we can reasonably look at well-validated scales, screening instruments, and diagnostic criteria to identify people who might be experiencing an addiction. But when it comes to digital devices, we mostly are at a loss. One factor we can be confident about is that time spent online is not a reliable indicator of a problem. Being routinely engaged with social media is a requirement for many corporate jobs, while competitive gaming and/or online streaming of games has become a popular pastime and money maker. How can psychiatrists distinguish a healthy, though time-consuming, habit from an unhealthy psychiatric condition?

As noted above, the seven proposed technological addictions are largely unique entities with distinct risk factors and motivations, but at times they share some thematic elements such as thrill seeking, escapism, and financial ramifications. Therefore, the work carried out to define online gaming disorder can provide a framework for diagnosing other technological addictions. Under the current DSM-5 entry, online gaming disorder is likely present if someone meets five of the following nine symptom criteria over a 12-month period:

Being preoccupied with video games.

Experiencing withdrawal symptoms when video games are inaccessible.

Requiring more and more playing time to gain the same level of satisfaction.

Being unable to cut down on game playing despite efforts to do so.

Giving up other activities to play more frequently.

Deceiving family members about how much time is spent gaming.

Using video games to alleviate negative moods.

Jeopardizing jobs or relationships due to gaming.

Continuing to play video games despite knowledge of adverse consequences.

When considering whether patients might have a technological addiction, consider whether their online activities may be related to another psychiatric diagnosis. As Robert Glick, M.D., director of the Center for Psychoanalytic Training and Research at Columbia University from 1997 to 2007 taught us, “the chief complaint is often nothing more than a dysfunctional solution to a yet unidentified problem.” The problematic engagement with technology may be a coping mechanism, maladaptive behavior, or a self-medication for an underlying psychiatric condition. Since online gaming disorder became recognized, many families have jumped on it to explain problems in their children, when emergent depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia is the true diagnosis. Having an external culprit like video games or social media is a less stigmatizing—and thus more easily accepted—problem than a psychiatric illness for many.

Treatment Options and Goals: How to Manage a Modern Necessity

Just as the diagnostic criteria for the seven proposed technological addictions remain a work in progress, the guidance on how to treat patients with such a disorder remains so as well. The best advice currently is to rely on what works well across the broad addiction sphere: providing patients an integrated treatment that incorporates addiction psychotherapy, pharmacological treatment of other psychiatric disorders, and possibly mutual-help (otherwise known as 12-step) facilitation.

Counseling Guidance

Be empathic and curious.

Educate about problematic use and addiction.

Advise.

Follow up.

Refer, if necessary.

Source: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, NIAAA.NIH.gov.

The first approach should be professional assessment and counseling, which many general psychiatrists should be prepared to take on themselves. As with substance use disorders and other behavioral addictions, educating and counseling patients about their technological addiction is based on empathy, curiosity, and nonjudgmental support. That a proposed disorder is not yet codified in text does not disqualify someone from having a legitimate psychiatric concern.

After initial assessment and counseling, motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral therapy that includes mindfulness techniques may be an effective strategy in the management of many technological addictions. Furthermore, peer support groups are now available for all the technological addictions listed.

Some psychiatrists may wonder whether patients with a technological addiction should be discouraged from using technology-based treatment such as internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy or online 12-step programs, since this may potentially keep their problem front and center. To that, one could argue that our field uses opioids to treat opioid use disorder and nicotine patches for smoking cessation, so we have successfully gone down this road before. The rise of online peer support and recovery groups has been extremely helpful in addiction treatment (even more so during the pandemic), as individuals now can connect with others in a comforting and, if desired, truly anonymous manner.

When it comes to medications, things get tricky, as no medications are approved for any behavioral addiction, technology based or otherwise. The optimal use of medications for most patients is in the management of common psychiatric comorbidities like depression or anxiety, which have been shown to worsen the problematic behavior. If you think a patient might need some medication assistance, there are a few options to consider, but caution is warranted as the evidence is very limited. Patients with internet gambling or internet shopping disorder, who have an impulsivity-driven technological addiction, might respond to naltrexone, which has moderate evidence of efficacy in non-internet gambling disorder. Patients with a compulsive technological addiction like cybersex may benefit from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which are first-line medications for obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders; SSRIs also decrease libido as a side effect, which may be an additional benefit for treating cybersex addiction. Finally, methylphenidate might help manage problematic internet surfing, based on some limited evidence in studies among people with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Conclusion

Though data on the prevalence of technological addictions are sparse, most people use computers, tablets, and smartphones regularly with great benefits and no serious adverse consequences. Research on the phenomenology and nosology of these illnesses will help us further elucidate the distinction between problematic and nonproblematic use of technology, especially in children and young adults. Another area of new research will involve emerging technologies. By the time clinicians get a firmer grasp of today’s ailments, the technology of tomorrow—such as virtual reality and smart devices powered by artificial intelligence—will be commonplace enough to bring about a host of new problems. Finally, we will need to be ready to guide our patients, our colleagues, and the general public on how to best handle technology with an eye on maximizing its enormous potential for fulfillment, gratification, and happiness while minimizing its significant risks for dissatisfaction, misery, and despair. ■

Disclosure statement:

The author receives revenue from APA Publishing but has no other financial conflicts to disclose.