Brief IPT Found Effective for Perinatal Depression

Abstract

Individuals receiving eight weeks of an interpersonal therapy (IPT) called MomCare experienced a greater reduction in depression symptoms than those who received counseling and maternity social services.

A brief course of interpersonal therapy (IPT) may help to decrease depressive symptoms in pregnant individuals, a study in JAMA Psychiatry has found.

Previous studies have shown the benefits of IPT—a psychotherapy that focuses on reducing interpersonal conflicts and building social support—for the treatment of perinatal depression. The new trial adds more robust evidence, as it included over 200 pregnant individuals from multiple racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

“Pregnancy is a period that already involves regular contact with the health care system,” study co-author Elysia P. Davis, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at the University of Denver’s SEED Research Center, told Psychiatric News. “That gives us an opportunity to integrate mental health support into ongoing care in a way that is more accessible.”

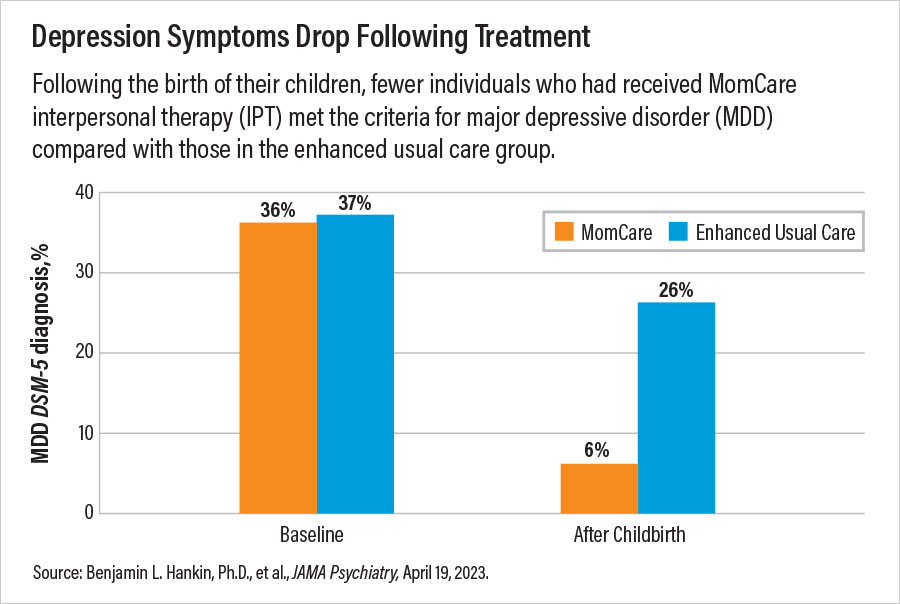

For their study, Davis and colleagues recruited 234 individuals aged 18 to 45 who were no more than 25 weeks’ pregnant from obstetrics clinics in the Denver metropolitan area. All participants reported elevated depressive symptoms—defined as a score of at least 10 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) screening tool; about 37% had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD), as indicated by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5.

The study participants were randomized to receive either eight, 50-minute individual sessions of MomCare (roughly once a week) or enhanced usual care. MomCare, an IPT intervention that was developed at the University of Washington, is meant to offer support during pregnancy. MomCare is also designed to be accessible to all individuals, Davis said. The program is offered in fewer sessions than conventional IPT (conventional IPT is typically 16 sessions), and therapists work with patients prior to the first session to identify key cultural considerations and barriers to care.

Participants in the enhanced usual care group received mental health counseling and maternity social services, including information on housing and essential items, in addition to standard maternity care.

Over the course of their pregnancy, mothers receiving MomCare experienced a greater decline in depression symptoms than those who received enhanced usual care, as assessed both by the EPDS and the 20-item Symptom Checklist (SCL-20). For example, average SCL-20 scores dropped by around 0.55 points per week in MomCare recipients compared with 0.15 points per week for those in the enhanced usual care group, leading to noticeable differences in symptom improvements after just six weeks. After giving birth, just 6.1% of mothers receiving MomCare still had a MDD diagnosis, compared with 26.1% of mothers in the enhanced usual care group.

“We were blown away by how quickly and how dramatically some of these symptoms improved,” Davis said. “It was really important for us to set up an intervention that could be completed before birth, and the results surpassed our expectations.”

Davis told Psychiatric News that she and her colleagues are continuing to track the outcomes of the mothers and babies from the study to see if the benefits of MomCare extend into childhood. They are also implementing a MomCare group intervention that they believe could be offered directly at maternity clinics, further increasing the number of patients who could be supported by the treatment.

“Group sessions work well for IPT, since it provides immediate social connections by bringing together people facing similar challenges,” she said.

This study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. ■