Direct-to-Consumer Ads Get Patients to Act

Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising (DTCA) appears to result in no widespread adverse health effects, according to a nationwide survey of patients’ experiences with such ads.

Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising (DTCA) appears to result in no widespread adverse health effects, according to a nationwide survey of patients’ experiences with such ads.

The phenomenon of pharmaceutical advertising pitched to patients appears also to have promoted discussions with physicians resulting in diagnoses that might not have been made otherwise, according to the survey published online in the February 26 Health Affairs.

“We found that direct-to-consumer advertising is a factor causing a lot of people to seek a physician to talk about problems they hadn’t talked about before,” said Robert Leitman, M.A., an author of the report. He is division president for health care research at Harris Interactive Inc., a survey research firm headquartered in Rochester, N.Y.

Notably, among the most common new diagnoses resulting from such discussions was depression. “That tells us, and should tell physicians, that there is a pool of people out there who are depressed but undiagnosed,” Leitman told Psychiatric News.

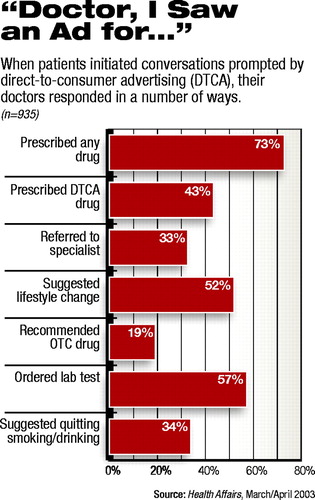

The most common action taken by a physician in response to a discussion prompted by advertising was to prescribe medication; 72.9 percent of the sample reported being prescribed any drug by their physician. A little more than 43 percent were prescribed the advertised drug.

In a substantial number of cases—32.6 percent—patients were referred to a specialist. Leitman said that in the case of new diagnoses of depression, especially, the effect of DTCA might be a “two-step process” resulting in a referral to a specialist.

“One of the most common things we see is that when patients go to a physician [about a condition related to advertising they had seen], they are referred to a specialist,” he observed.

Mary Helen Davis, M.D., chair of APA’s Committee on Public Affairs, said she believes much of the impact of DTCA is at the primary care level. But she agreed the phenomenon has had a profound impact on patients, physicians, and the health care system in general—for good and for ill.

“It has its pros and cons,” she said. “Obviously, anything that reduces stigma and provides useful information can have a positive impact. But there has also been a concern about overdiagnosis, raising the cost of health care by prompting patients to go a physician seeking the newest, most expensive designer drug when there are other fully efficacious drugs that are less expensive.”

Davis said also that DTCA is only one component of a more encompassing phenomenon that definitely impacts both primary care physicians and specialists—the increasing sophistication of patients generally regarding their own health and medical care. Moreover, Davis said that the Internet has had an even greater impact than DTCA.

“What I see more of in my own practice is Internet exploration and many more questions about something someone found on the Net,” she said. “People are becoming more knowledgeable in general about their medical care. That has been a major change in the last few decades, from an authoritarian medical model to a more collaborative model. Patients have taken more responsibility and have the capacity to do research at their fingertips.”

She is a partner in Integrative Psychiatry in Louisville, Ky., and an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Louisville School of Medicine.

Leitman and colleagues noted in their report as well that DTCA is only one of many health information sources influencing patients. Fifty-one percent of respondents in the survey said they were influenced by family or friends, 40 percent by broadcast media, 34 percent by print media, 33 percent by pamphlets in doctors’ offices, 33 percent by another doctor, 16 percent by the Internet, and 17 percent by a pharmacist.

No Trivial Conditions

The survey was conducted by a team of researchers from Harvard University, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harris Interactive. Telephone interviews with a national probability sample of 3,000 adults were conducted between July 2001 and January 2002 using random-digit dialing and random household-member selection. A $10 incentive was offered for completion of the survey, and a toll-free number was offered so that respondents could complete the survey at a convenient time. The response rate was 53 percent.

Approximately 86 percent of the sample had seen or heard a direct-to-consumer ad in the previous year, and about 35 percent of the sample had a physician visit during which direct-to-consumer advertising was discussed. Twenty-five percent of the sample received a new diagnosis, and more than half also reported actions taken by their physician other than prescribing the advertised drug.

The most common new diagnoses were allergies (9 percent), high cholesterol (6 percent), arthritis (6 percent), hypertension (6 percent), diabetes (5 percent), and depression (5 percent).

Much criticism of DTCA has been directed at its possible impact on health care costs generally, while reaping windfall profits for the pharmaceutical industry.

Leitman acknowledged that the survey did not address such cost-related issues. “What we did find is that there wasn’t a lot of trivial activity [generated by DTCA],” he said. “Diabetes, depression, high-blood pressure, high cholesterol—these are high-priority conditions. What don’t appear on the list are trivial diagnoses like hair replacement.”

Survey Criticized

The survey article was accompanied in the journal by several others, including one by Thomas Bodenheimer, M.D., whose article called the survey “little more than an advertisement for drug advertisements.”

Bodenheimer criticized the study methods for what he called overinterpretation of patient responses and for the failure to include a control group of patients who had not seen drug advertising.

But Bodenheimer was especially critical of the survey for failing to ask respondents about the cost of drugs—the subject that he called “the expensive elephant in the living room.”

Noting the steadily rising cost of prescription drugs, Bodenheimer said that between 1997 and 2000, 28 percent of the increase in drug spending “resulted from newer, higher-priced drugs that were replacing older, less-costly drugs, and 48 percent came from the increasing number of prescriptions written.”

He added, “TV drug advertising is a strategy used by the pharmaceutical industry that covers up the astounding statistic that over the past 10 years, only 15 percent of the newer, expensive drugs arriving on the market offer significant improvements over already existing, lower-price medications.”

Leitman told Psychiatric News that the effects of DTCA may ultimately boil down to a question of medical ethics.

“If people get diagnosed earlier than they might have and if the condition is important, does it have an impact on cost?” Leitman asked. “I would say we haven’t done the math. If the condition were diagnosed later, it might cost more. And if the condition is diagnosed earlier and it costs more, what we have is a question of medical ethics: Is it a good and desirable expense? An argument can be made that it is a good expense.”

“Consumers’ Reports on the Health Effects Of Direct-To-Consumer Drug Advertising” is posted on the Web at www.healthaffairs.org/WebExclusives/Weissman_Web_Excl_022603.htm. ▪