Factors Collide to Increase Suicide Risk in Elderly

People over age 65 have the highest suicide rate of any age group. Preliminary results from the first psychological autopsy study of completed suicides in the United States suggest that a combination of factors pushes them over the edge.

People over age 65 have the highest suicide rate of any age group. Preliminary results from the first psychological autopsy study of completed suicides in the United States suggest that a combination of factors pushes them over the edge.

Researchers at the University of Rochester Center for the Study and Prevention of Suicide in Rochester, N.Y., studied 86 people who completed suicides in nearby Monroe and Onondaga counties. The mean age of the group was 68. A control group was matched by age, sex, race, and county of residence. The majority of both groups were Caucasian, and men outnumbered women 3 to 1.

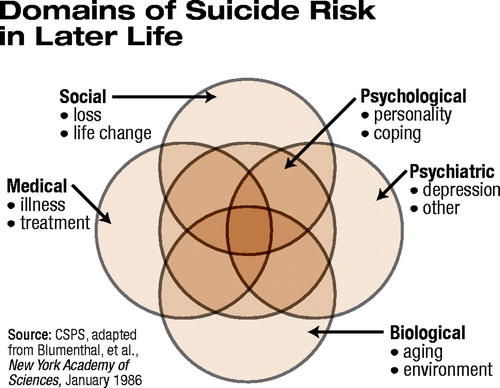

“Our preliminary findings suggest that mood disorders—in particular major depression—previous suicide attempts, physical illnesses or decline, and loss of social support are significant risk factors for suicide in the elderly. We believe our final analysis will show that the balance is tipped toward suicidal behavior in the elderly when two or more of these factors collide” (see chart), said lead researcher Yeates Conwell, M.D., in an interview with Psychiatric News.

Conwell codirects the suicide study and prevention center with Eric Caine, M.D., chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Rochester. Conwell is also associate chair for academic affairs in the department of psychiatry there.

The researchers worked with the medical examiner’s office to identify persons who had committed suicide and then contacted the next-of-kin for informed consent. If consent was given, “we obtained the individual’s autopsy report and medical and psychiatric records and interviewed family members, friends, and health care providers,” said Conwell.

The researchers constructed individual profiles using several measures including a suicide behavior profile, structured clinical interview for psychiatric diagnoses, a life-events profile, a health history, and tests to determine functioning, said Conwell.

The researchers found that 73 percent of the 86 people who died by suicide had a mood disorder, and 50 percent had one or more episodes of major depression. In the control group, only 9 percent had a mood disorder, and 5 percent had a major depressive episode.

Nearly 34 percent of the group who had died by suicide had a substance use disorder, compared with half that percentage in the control group, said Conwell.

“A study by my co-investigator Paul Duberstein, Ph.D., in the August 1994 journal Psychiatry showed that people who committed suicide later in life often had neurotic personality traits, more rigid cognitive processes, and limited coping skills,” said Conwell.

Neurotic personality traits, such as a tendency to feel anxious and depressed, can tip the balance toward suicide when adverse life events occur simultaneously, he added.

The elderly who completed suicide had more physical illnesses and impaired daily functioning than their matched controls, said Conwell. “We found that they also participated in social activities less often than the control group,” he said.

“We know from epidemiological studies that men are three to four times more likely to commit suicide than women during their lifetimes. White men over the age of 85 have nearly three times the risk of suicide as white men at or below age 60, while white women experience a slight decline in suicides after age 5,” said Conwell.

“In most other countries, the suicide rate of women continues to increase steadily after midlife, although at a much slower rate than that of men. What then protects women from completing suicide as they age? Possible clues are that they use less lethal means in the suicidal act than men, who favor handguns, and they are more likely to forge confidential, supportive relationships with others,” said Conwell.

Suicide acts are more likely to result in death among the elderly in general than among younger individuals for many reasons, according to Conwell. “Their physical condition is more frail, which impairs their ability to survive a self-inflicted injury; they are more isolated and so less likely to be rescued in time; their acts are premeditated; and they often own guns, which are in their home,” said Conwell.

The primary means of suicide completion in the psychological autopsy study were firearms (48 percent), drug ingestion (16 percent), and hanging (15 percent), said Conwell.

Twenty-five percent of the elderly who committed suicide had attempted suicide before, compared with 2 percent in the control group, said Conwell.

“Other studies have shown that the ratio of attempted to completed suicides in the elderly is about 1 to 4 compared with 1 in 15 in the general population,” he continued. “Our preliminary findings confirm that the elderly need aggressive, comprehensive interventions that address their social, psychological, and medical needs. Because research has shown that the elderly who committed suicide were seen recently by their primary care physicians, psychiatrists and mental health professionals should collaborate with primary care professionals to improve the detection and treatment of depression.”

Some promising models of collaboration are the IMPACT (Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment) project and PROSPECT (Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly Controlled Trial) (Psychiatric News, April 4), according to Conwell.

The National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has several data sets on trends in aging, including death rates, on its Web site at www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/otheract/aging/trenddata.htm. ▪