In Families With Psychosis, The Numbers Tell a Story

Several years ago, the book and movie “A Beautiful Mind” made quite a splash. They had to do with the life of mathematical genius and Nobel Laureate John Nash. One could get the impression from both the book and movie that it was purely coincidental that Nash, a math genius, developed schizophrenia. But maybe it was more than chance, a new study suggests.

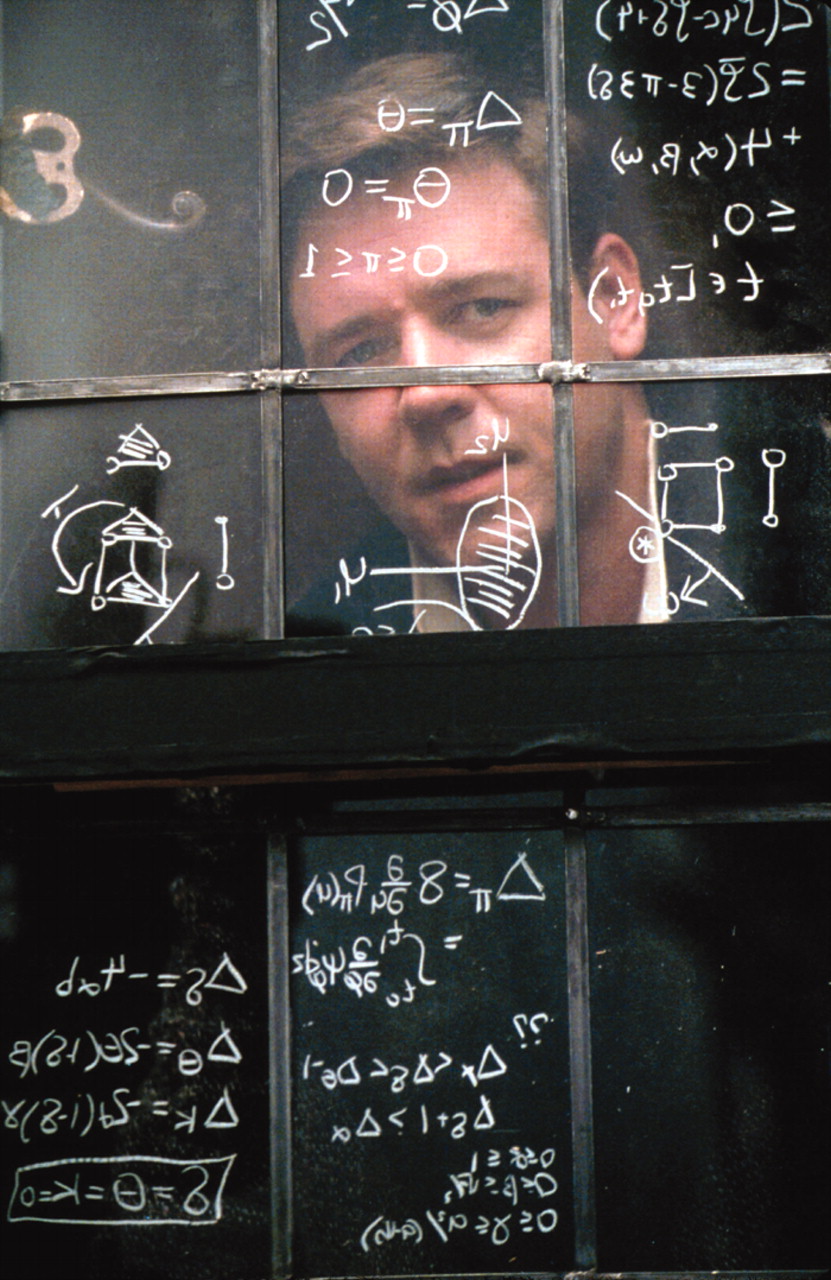

Above is a still from the movie “A Beautiful Mind” about John Nash, a math genius who had schizophrenia. Nash illustrates what an Icelandic psychiatrist has now found—that there may be a link between psychosis and math talent.

The study, conducted by Jon Karlsson, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Institute of Genetics in Reykjavik, Iceland, has found an intriguing relationship between math talent and psychosis susceptibility in the Icelandic population. Results were published in the April British Journal of Psychiatry.

“I know of no other quantitative study demonstrating a link of psychosis to mathematical ability,” Karlsson told Psychiatric News.

Lynn DeLisi, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at New York University, agreed, saying, “I don't know of any other study that has suggested that mathematical abilities are higher in families with psychosis— so this is very interesting.”

There is ample evidence of an increased risk of mental illness among highly creative persons and their relatives. Few such studies, however, have been conducted to determine whether extremely successful scholars might also be at such an increased risk. Karlsson thus viewed the stability of the Icelandic population and the excellent demographic records in Iceland as a unique opportunity to see whether there might be an increased risk of mental illness—specifically of hospital-treated psychosis—in scholars and their first-degree relatives.

In his first analysis, he focused on 180 young men who had been top graduates of two Icelandic university preparatory schools, one in Reykjavik and one in Akureyri, between 1871 and 1960, as well as on 1,016 of their first-degree relatives.

He then attempted to see whether their risk of psychosis was significantly greater than what would have been expected if their risk equaled that of the general Icelandic population, and the answer was yes.

The top 180 male graduates were expected to have one instance of hospital-treated psychosis if their risk equaled that of the general population; the observed number was four (all cases of schizophrenia). Their 1,016 first-degree relatives should have included eight cases of psychosis; the observed total was 22 (eight schizophrenia and 14 affective disorder).

These results, Karlsson wrote, “leave little doubt that the altered levels of brain activity seemingly associated with risk of psychosis can lead to superior performance in academic settings.... Most of the individuals surveyed here lived in the period before the educational emphasis shifted to mathematics and science, but even in college subjects covered a century ago, an increase in psychosis was apparent among the gifted students.”

In a second analysis, Karlsson attempted to get a better idea of whether it is top academic performers in all areas, or only top academic performers in some areas, who are at increased risk of psychosis.

This time he focused on 338 first-degree relatives of 90 top male humanities scholars in Reykjavik College from 1931 to 1960; 347 first-degree relatives of 90 top female humanities scholars in the college during those years; 339 first-degree relatives of 90 top male math scholars in the college during those years; and 349 first-degree relatives of 83 top female math scholars in the college during those years.

He then assessed whether the incidence of hospital-based psychosis in the first-degree relatives of the top humanities performers was significantly greater than what would have been expected for them if their risk equaled that of the general population. He found that it wasn't. He then attempted to see whether the incidence of hospital-treated psychosis in the first-degree relatives of the top math performers was significantly greater than what would have been expected for them. The answer was yes. There were seven cases of psychosis among relatives of top male math performers, compared with an expected rate of only three cases, and there were 10 cases of psychosis among the relatives of the top female math performers, compared to an expected rate of only three cases.

Thus, “the risk of psychosis does not seem to appear in groups preparing for careers in languages, literature, and jurisprudence, for example,” Karlsson wrote in his study report, “but is more definitive in those headed for science or mathematics.”

Then, in his third and final analysis, Karlsson decided to further explore what appeared to be a relationship between math talent and psychosis risk. He evaluated the risk of hospital-based psychosis in 90 male students who distinguished themselves as the highest performers on the written final math test at Reykjavik College from 1930 to 1960—young men preparing for careers in math, physics, chemistry, astronomy, engineering, architecture, and medicine—as well as in 365 of their first-degree relatives. He found that the risk of hospital-based psychosis was significantly greater in the whole group than expected if their risk equaled that of the general Icelandic population. Instead of the expected four instances of psychosis in the whole group there were 11 instances— four of schizophrenia and seven of affective disorder.

So it looks as though there may be a relationship between math talent and a risk of psychosis, Karlsson concluded.

“Psychotic disorders,” he suggested, “might be associated with some favorable effect, as this would explain their surprisingly high frequency in all human populations. Geneticists refer to such systems as balanced polymorphisms, mutant genes tending to exist at unexpectedly high levels if their heterozygous carriers benefit in some manner from the phenomenon....”

Although DeLisi admitted to Psychiatric News that she found the results of Karlsson's study intriguing, she said that she would nonetheless be cautious about them “because the diagnoses were only through records, and I suspect that many cases he was calling schizophrenia were really bipolar affective disorder.... I would also like to see pedigrees and how the co-transmission of these traits occurs, but we don't see it at all. I also think that some further careful studies need to be done to attempt to replicate these findings before people make too much out of them.”

No external funding was provided for the study.

An abstract of the study, “Psychosis and Academic Performance,” is posted online at<http://bjp.rcpsych.org/cgi/content/abstract/184/4/327>.▪

The British Journal of Psychiatry 2004 184 327