Education on Medication Adherence Will Reduce Costs, Improve Outcome

Reducing unnecessary antipsychotic polypharmacy through prescriber education and improving patients’ adherence to their antipsychotic medication regimens using proven patient education techniques is associated with large reductions in expenditures within the Medicaid system, new data suggest.

“Antipsychotic medications are the cornerstone of therapy,” noted Dilip Jeste, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and neurosciences and the Estelle and Edgar Levi Chair in Aging at the University of California at San Diego School of Medicine. “It has been known for some time that medication adherence associated with schizophrenia is not great.”

The hope was that the advent of the second-generation antipsychotics—marketed for their broad efficacy and improved side-effect profiles—would lead to improvements in adherence, but that has yet to be shown conclusively.

“We did a study a few years ago with our VA population, and what we found was that it was the glass-half-empty, glass-half-full story: we used two major indicators of medication adherence in the study. With one measure, the newer medications looked significantly better than the older typicals, but with the second measure, there was no statistically significant difference.” Other research has come to similar conclusions.

If the newer, second-generation medications are really better, Jeste said, then they should translate into improved patient outcomes, including medication adherence. Improved adherence and improved clinical outcomes should then translate into cost reductions for the overburdened Medicaid system.

Jeste and his colleagues set out to determine whether adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medications directly impacts health expenditures and to define risk factors that lead to a patient’s nonadherence. Their study, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and the Department of Veterans Affairs, appeared in the April American Journal of Psychiatry.

The researchers analyzed Medicaid data, including eligibility and claims, for San Diego County from 1998 to 2000. Pharmacy records were tracked to determine antipsychotic medications filled, and data from the San Diego County Adult Mental Health System were used to track inpatient and outpatient expenditures. They included only data on oral antipsychotic medications filled and excluded data from individuals who were dually eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid.

Patients were classified into one of four oral medication groups: first-generation (“typical”) antipsychotic, clozapine, second-generation antipsychotics, or antipsychotic polypharmacy. (Within the second-generation classification, the researchers analyzed subgroups for risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine—the three available during the study period; however, no statistically significant differences were found among the three drugs.)

“We wanted to know not only the typical versus atypical question, which is only a part of the cost issue, [but also] what the overall adherence was, what the risk factors are for nonadherence, and what the overall consequences are for nonadherence,” Jeste told Psychiatric News.

“We found that only 41 percent of patients adhered to their medications,” Jeste said. Adherence was defined as filling their medications between 80 percent and 110 percent of the expected refill rate. For example, if a person was written a prescription for a two-month supply of an antipsychotic on March 1 and then did not get another prescription filled for 10 weeks, the person would have theoretically taken eight weeks of medication over 10 weeks, an 80 percent adherence rate.

Patients who had only 50 percent of their expected refill rate were termed “nonadherent.” Those who filled prescriptions between 50 percent and 80 percent of the expected refill rate were termed “partially adherent.” Those who filled their prescriptions at more than 110 percent of the expected rate (for example, filling prescriptions for eight weeks of medication over seven weeks, for a rate of 114 percent) were termed “excess fillers.”

Jeste and his colleagues found that of a total of 1,619 patients analyzed over the three years of claims and expenditure data, 24 percent were nonadherent, 16 percent partially adherent, 41 percent adherent, and 19 percent were excess fillers.

“The excess fillers are an interesting category,” Jeste noted. Until Jeste started analyzing the data, he had not really thought about there being such a group. “These people are not really “overadherent”—they simply fill more prescriptions than they theoretically should.”

Digging deeper, Jeste found that the majority of this group was accounted for by antipsychotic polypharmacy. And, Jeste pointed out, there really is no evidence to back up the practice of polypharmacy (see Original article: page 1).

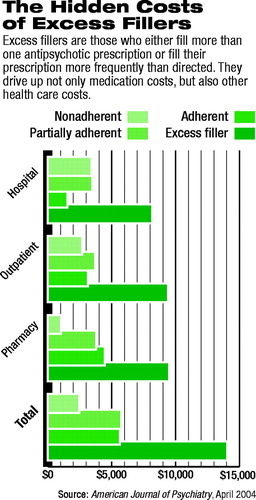

The excess fillers are the most expensive group, Jeste explained (see chart). “Whether you consider pharmacy costs or you look at their significantly higher psychiatric as well as medical hospitalizations, they are the largest cost center.”

The excess fillers are the most expensive group, Jeste explained (see chart). “Whether you consider pharmacy costs or you look at their significantly higher psychiatric as well as medical hospitalizations, they are the largest cost center.”

What is not clear, he said, is what is driving up the costs. “Are these really the sickest patients? Or was their medication lost or stolen, so they had to [get a refill] before they should have? Or was the polypharmacy driving the costs across the board?”

They probably are the sicker patients, Jeste postulated, although there is no way to determine that with the data at hand.

“If you look at the cost differential between the excess fillers and the adherent group, the total cost difference is something like $4,500 per year,” Jeste noted. The excess-filler group’s costs are significantly higher for pharmacy and outpatient services compared with the adherent group, and the hospital costs of excess fillers are more than twice those of adherent patients.

“This is clearly the group to target to make sure they are being treated properly,” Jeste concluded. “But we’re not just talking about the cost of a single medication versus a cheaper medication. It is very important to realize that adherence is a more general phenomenon and must be addressed as such.”

For example, Jeste said, the nonadherent group had the lowest pharmacy costs because they were not taking their medications as directed; they also had the lowest outpatient costs because they did not keep their clinic and therapy appointments. Unfortunately, that translated into the highest overall hospital costs for any of the groups.

Clearly patient education programs are necessary, Jeste said. Patients must be helped to understand the importance of taking their medications correctly, including understanding the consequences of not taking them. Further, he added, physicians must do more to improve patient adherence through careful selection of medication to maximize efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. Prescribing multiple antipsychotics rarely boosts efficacy to the same degree as it boosts adverse effects, he noted.

The study, “Adherence to Treatment With Antipsychotic Medication and Health Care Costs Among Medicaid Beneficiaries With Schizophrenia,” is posted online at http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/abstract/161/4/692. ▪

Am J Psychiatry 2004 161 692