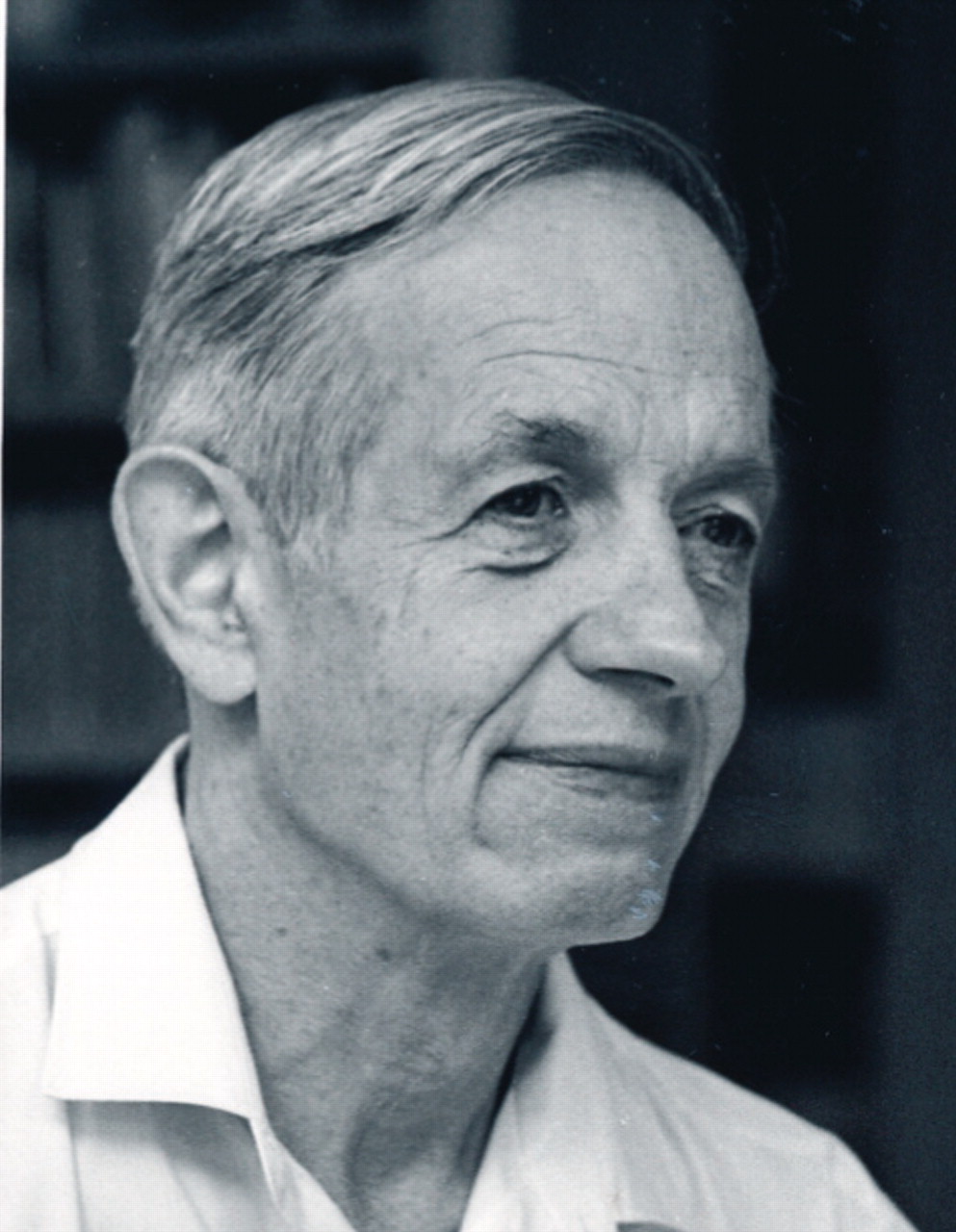

Nobel Laureate John Nash to Give Convocation Lecture

People with mental illness are in most ways no different from anyone else: they are brothers and sisters, husbands and wives, and sons and daughters who love their families, aspire to live a productive and meaningful life, and want to leave a positive mark on this world. But what happens when their mental illness lays claim to their consciousness, to their everyday reality, to the core of who they are?

That's a question for Nobel laureate John Nash Jr., Ph.D., who, at the age of 30, descended into the debilitating blackness of severe paranoid schizophrenia. Despite the odds, however, his perseverance and genius eventually led to his winning the 1994 Nobel Prize for Economics for landmark work he had begun in the 1950s on the mathematics of game theory. His inspiring story was adapted in the movie “A Beautiful Mind,” which won the best-picture Oscar for 2001.

During what is expected to be an unforgettable evening, Nash will present the William C. Menninger Memorial Lecture at APA's Convocation of Fellows on Monday, May 21, at 5:30 p.m. in the San Diego Convention Center.

Nash was born in Bluefield, W.Va., in 1928. Early on he excelled at mathematics and won a scholarship to Carnegie Mellon University. He did so well that upon graduation in 1948

he was awarded a master's degree in addition to his bachelor's degree, and went on to earn a Ph.D. from Princeton University in 1950. From 1951 until his resignation in 1959, he was a faculty member at M.I.T. As an undergraduate, he began work on what is now regarded as the basic building block of the theory of games. His reputation as a mathematical genius was firmly established by his ability to solve major problems in pure mathematics using original methodology.

In 1957 Nash married a woman he had met while she was a student at M.I.T. During his wife's pregnancy in 1959, he became increasingly delusional and was forcibly hospitalized on several occasions. He eventually refused to take medication and for years was a ghostly figure on the Princeton campus, believing he was engaging in research. It was in the early 1990s that acquaintances noticed that he appeared to be recovering from his illness.

According to his autobiography, “[W]hen I had been long enough hospitalized... I would finally renounce my delusional hypotheses and revert to thinking of myself as a human of more conventional circumstances and return to mathematical research. In these interludes of, as it were, enforced rationality, I did succeed in doing some respectable mathematical research.... But after my return to the dream-like delusional hypotheses in the later 60s, I became a person of delusionally influenced thinking but of relatively moderate behavior and thus tended to avoid hospitalization and the direct attention of psychiatrists.

“Thus further time passed. Then gradually I began to intellectually reject some of the delusionally influenced lines of thinking which had been characteristic of my orientation. This began, most recognizably, with the rejection of politically oriented thinking as essentially a hopeless waste of intellectual effort.”

Despite having divorced his wife for her role in having him hospitalized, in 1970 she took him in to save him from homelessness, and they remarried in 1991. Three years later, he won the Nobel Prize. This is no fairytale ending; it provides powerful support for the growing movement within psychiatry to help patients with severe mental illness focus on recovery, not pathology.