Aging and Mental Health: Bad News and Good News

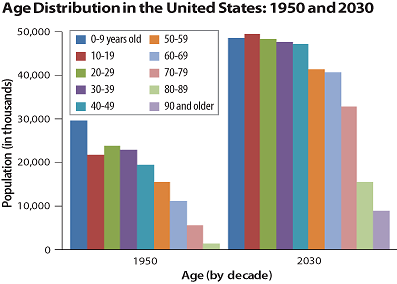

The world is aging—and rapidly so. By 2030, there will be more than 72 million Americans over age 65, more than twice their number in 2000. With increasing longevity and declining birth rates in the world, the number of older individuals will exceed that of children for the first time in human history. These remarkable changes will have significant impact on practically every aspect of our lives. In this column I will discuss good news and bad news related to the aging of the population in terms of mental health.

Let us start with the bad news. The demographic changes are especially alarming in terms of mental illness. During the next two decades, we will witness an unprecedented rise in the number of older adults with psychiatric disorders, at a rate that is growing faster than that of the general population. The reasons reflect both negative and positive factors. On the negative side, several studies have suggested that the aging baby boomers have a higher risk of developing depression, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders than people born before World War II. Additionally, increasing numbers of older people will mean greater prevalence of late-onset mental illnesses.

On the positive side, improved treatment for mental disorders and healthier lifestyles will lead to more patients with mental illness living into old age. Presently, people with serious mental illness have a 20- to 25-year shorter lifespan than the population at large; this difference in longevity will narrow in the near future. Also, with progressive reduction in social stigma against mental illness, a greater number of seniors will seek and receive treatment for their psychopathology.

Unfortunately, we are ill prepared to meet the coming needs for geriatric mental health care. In fact, the seismic demographic shift in the number of mentally ill older adults is paradoxically coupled with a decreasing number of mental health care providers, especially geriatric psychiatrists. Today there are about 1,700 board-certified geriatric psychiatrists in the United States—one for every 23,000 older Americans. That ratio is estimated to diminish to one geriatric psychiatrist for every 27,000 individuals 65 and older by 2030. Yet, little is being done to address this challenge. Already geriatric psychiatric services are in high demand, and specialists are in short supply. The trainee pool is a critical issue. Currently, there are 120 geriatric psychiatry fellowship training slots nationwide, but only half of them are filled. Psychiatry residents are drawn away from geriatric psychiatry fellowships, at least partly because of financial concerns over large student loans. Medicare reimbursements are decreasing, and the reimbursement system as a whole makes psychiatric care difficult to access for older patients. The dual stigma against aging and mental illness also makes geriatric psychiatry less attractive to many trainees.

Now the good news: contrary to general belief, getting older is often associated with being happier, more productive, and more functional—even in older adults with mental illness. Increasing numbers of people in their 70s, 80s, and even 90s are functioning well. In fact, research suggests that although older adults commonly experience some physical and cognitive decline, life satisfaction as well as psychosocial functioning tend to improve with aging. In our own studies, many older people rated their self-perceived successful aging and well-being near the top. In other words, contradicting the usual pessimistic stereotypes, older is frequently better. This is true for many people with mental illness too.

Research shows that a large proportion of patients with schizophrenia who live into old age feel better and are able to manage their illness more effectively. Indeed, a number of studies have shown that, after decades of mental illness, even a sustained remission is possible in a minority of patients. Most of us are familiar with the inspiring story of John Nash, a Nobel laureate in economic science who suffered from schizophrenia from his early 20s. After a quarter century of struggling with his illness, debilitating symptoms of schizophrenia began to improve. Nash was selected to present the William C. Menninger Memorial Lecture at APA’s 2007 annual meeting.

Aging-associated improvement in psychosocial functioning is common in the population and can be facilitated through psychosocial stimulation and support. Clinical investigators have developed a number of useful interventions for older people with mental illness, including cognitive-behavioral therapy, social-skills training, work rehabilitation, and intergenerational programs, among others. These treatment modalities not only enhance patients’ well-being, but also lead to progressive improvement in their ability to function productively in society. If appropriate illness management and psychosocial stimulation were provided on a larger scale, we could see a significant increase in the number of older adults who achieve sustained remission or recovery from serious mental illness.

Successful psychosocial aging should and can become the rule rather than the exception. As psychiatrists, we need to continue to combat stereotypes and promote the mental health and well-being of older individuals through comprehensive biopsychosocial management.

Older people are not a drain on the society; they are a major asset and resource. With their experience and wisdom, they can contribute on many levels. Aging of the population should not be viewed as a crisis, but rather as a transition opening up numerous opportunities.