People With Psychiatric Illness Tend to Partner With Each Other

Abstract

This mating pattern—which was not seen in patients with Crohn’s disease, type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis—may hold important implications for how we understand the familial transmission of psychiatric conditions.

As technology advances and the genomes of more and more patients with psychiatric illness are acquired, researchers are uncovering new information about the genetics of psychiatric disorders.

More traditional approaches, such as an assessment of mating patterns, can also inform what researchers understand of how psychiatric illness is transmitted across generations. One case in point is a study published in the April issue of JAMA Psychiatry that looked at the nature and extent of nonrandom mating within and across psychiatric conditions.

Nonrandom mating occurs when mated pairs are more phenotypically similar than would be expected by chance; it’s fairly common among humans who often find themselves attracted to people of a similar ethnic background, socioeconomic status, or personality.

By making use of extensive Swedish registry data, researchers from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden and the University of Carolina at Chapel Hill found that nonrandom mating also extends to a whole range of psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive-compulsive disorder, anorexia nervosa, substance abuse, social phobia, agoraphobia, and generalized anxiety disorder.

For the purposes of comparison, cases of select nonpsychiatric conditions of similar incidence and age at onset were also identified, including Crohn’s disease, type 1 and type 2 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Mating relationships were identified through marriage records or records of individuals being the biological parent of a child in other registers.

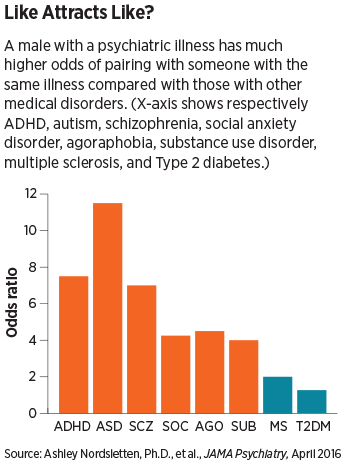

On average, an individual with any of the psychiatric disorders was two to three times more likely to have a mate with a psychiatric disorder as well, with slightly higher odds that it would be the same disorder. This connection was not seen in the nonpsychiatric disorders, with the exception of people with multiple sclerosis, who were about two times more likely to have a mate who had multiple sclerosis.

Julia Grant, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis, who has carried out studies showing nonrandom mating in cigarette and alcohol dependence, said she is not surprised by the findings.

“It makes sense when you think that people with behavioral problems would find themselves in environments where they could meet someone who shares their dispositions, such as a bar, church, or a support group,” she said.

When two people get married, the problems of one mate also run the risk of transferring to the other to some degree, Grant explained. For instance, if one person has alcohol dependence, the spouse may be more inclined to drink more and become dependent as well or might develop depression due to the stressed living environment, she said.

While the authors of the JAMA Psychiatry study acknowledged the findings could not rule out this possibility, they wrote, “In psychiatric samples, disorders exhibiting more marked spousal correlations and risk increases tended to be those that either emerge at an early age (for example, ADHD and ASD) or are associated with especially severe symptoms (for example, schizophrenia and substance abuse). Notably, some of these disorders (schizophrenia and ASD) are among those most likely to reduce overall reproductive success, suggesting that while these phenotypes may be under strong negative selection in the general population, they are being positively selected for within certain psychiatric populations.”

The authors continued, “While this finding does not imply a determinant risk in a given child, at the population level, this tendency toward spousal concordance will result in a subpopulation of offspring who differ substantially from the genetic mean and are, as a whole, at heightened genetic risk for psychiatric disorders.”

Andrew Heath, D.Phil., the Spencer T. Olin Professor of Psychology at Washington University, told Psychiatric News that while the risk to offspring is something that clinicians should monitor, he does not think clinicians should dissuade people with mental illness from finding opportunities to meet or become involved with peers. “I’m very much in favor of letting people decide their own lives.”

Heath added that he believes future studies should consider the potential role technology might be playing in the high nonrandom mating seen for some of these severe conditions like schizophrenia. “In this age of expanding social media and online support groups, it would be valuable to see if the rates of spousal correlation have been increasing, and I don’t think this has been touched on yet.”

This study was supported by a grant from the Swedish Research Council. ■

An abstract of “Patterns of Nonrandom Mating Within and Across 11 Major Psychiatric Disorders” can be accessed here.