APA Leaders Deliver Mixed Verdict on Federal Patient-Privacy Regulations

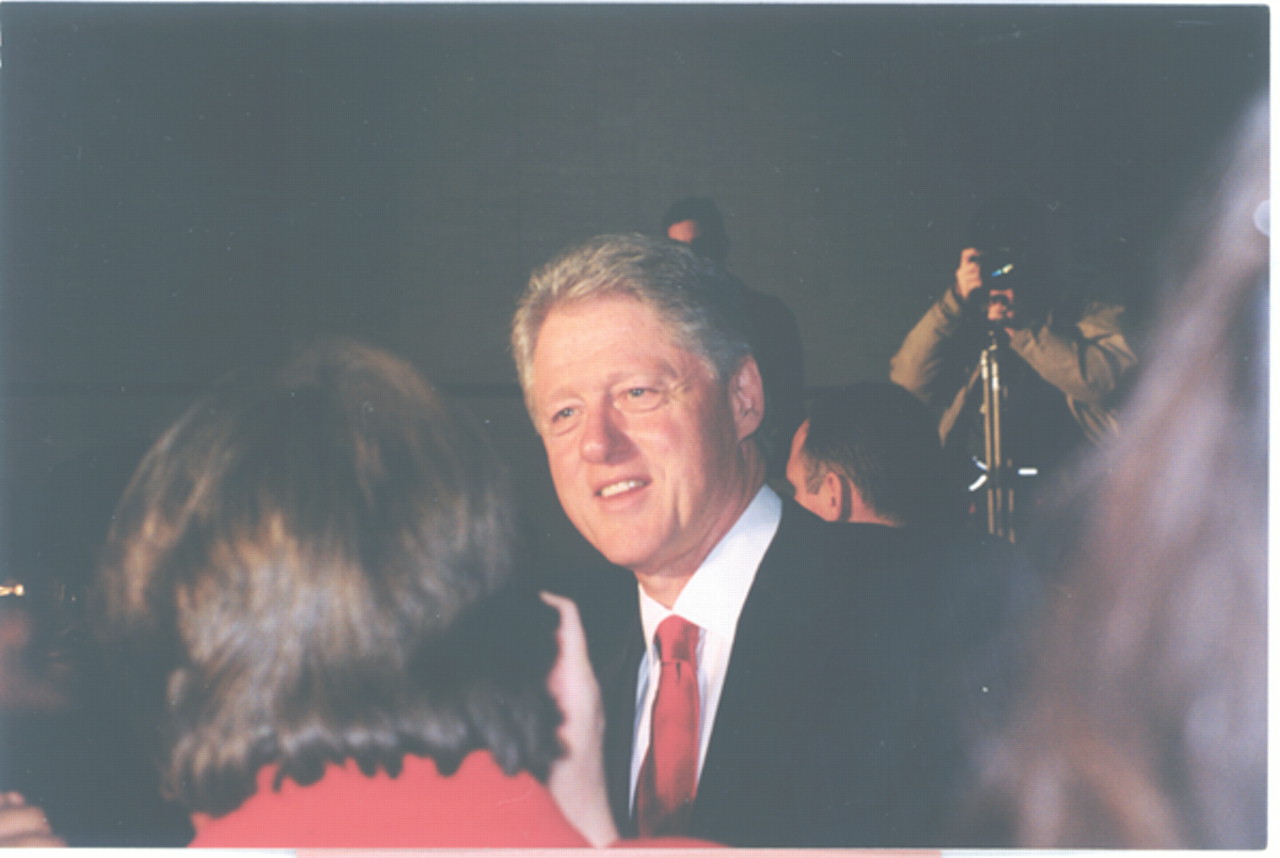

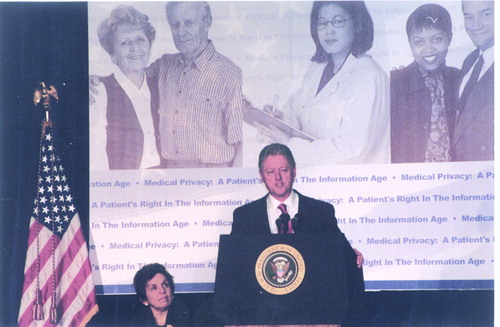

President Bill Clinton talks informally to the press after releasing the long-awaited final rules on medical record privacy in December.

A spokesperson at the Health Care Financing Administration said that the new rules are expected to go into effect in April without any changes. The Bush administration put a hold on implementation to allow time for review of the rules but is not expected to invite comments during the 60-day period.

As APA awaits further developments, the leadership is generally pleased with the regulations promulgated by the Clinton administration but will address some of the provisions it believes are harmful to patients or clinicians.

“APA plans to educate its members in the next few months about how to keep patient records secure and confidential,” said APA President-elect Richard Harding, M.D., who testified for APA on medical privacy on Capitol Hill and is a member of President Clinton’s National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics.

APA Medical Director Steven M. Mirin, M.D., attended the December briefing on Capitol Hill at which Clinton released the new rules and commented later that he was delighted that the President had highlighted privacy of psychiatric records in his announcement.

“Nothing is more private than someone’s medical or psychiatric records. Therefore, if we are to make freedom fully meaningful in the Information Age, we have to protect the privacy of individual health records,” said Clinton at the press briefing.

The sweeping privacy protections in the Clinton regulation build on provisions in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which Clinton signed into law in 1996.

Physicians, health plans, and health care clearinghouses have until December 28, 2002, to implement the rules, while small health plans with annual receipts of $5 million or less have until December 28, 2003.

The Clinton administration issued draft rules in October 1999 after Congress failed to enact privacy legislation by the August 1999 deadline imposed by HIPAA. APA criticized the draft regulation for not requiring patient consent before releasing personal health information for payment; treatment; and health care operations, excluding paper records and for preempting stronger state laws, among other points (Psychiatric News, November 20, 2000).

The final rules drew a mixed reaction from APA based upon a preliminary analysis of the approximately 1,500-page regulation.

Paul Appelbaum, M.D.: “Clearly, the regulation is an improvement from the draft rules and shows that APA had a significant positive impact on them.”

A positive change in the final rules requires patient consent before disclosing personal health information for health care operations, payment, and treatment purposes. The final rules also require a separate patient authorization to release psychotherapy notes, which indicates a greater understanding of their sensitivity, said Appelbaum.

The final rules also include these changes that APA recommended:

• Stronger state privacy laws can preempt weaker federal rules.

• Paper and electronic records are covered.

• Patients have the right to see their medical records and correct mistakes.

• Patients have the right to request a copy of their health records.

The final regulations also limit employers’ access to employee health records by requiring patient consent for purposes other than routine processing of health insurance information.

Flies in the Ointment

However, “the regulation falls short of providing meaningful informed consent,” said Appelbaum. “By allowing patients to sign a blanket consent form at the outset of treatment, individuals don’t know what future information will be disclosed and to whom.

However, “the regulation falls short of providing meaningful informed consent,” said Appelbaum. “By allowing patients to sign a blanket consent form at the outset of treatment, individuals don’t know what future information will be disclosed and to whom.

“The rules also define psycho-therapy notes narrowly to cover only the therapist’s written analysis of the patient’s remarks or a conversation during a counseling session. I believe that other sensitive information such as the initial patient evaluation should be covered also,” said Appelbaum.

Also, requiring psychiatrists to keep psychotherapy notes separate from the rest of the patient’s medical record creates an administrative burden, observed Appelbaum.

The final rules, however, do not prohibit physicians from asking patients to sign separate consent forms for subsequent disclosures of their psychiatric records, he noted.

Certain gaping loopholes also undermine meaningful patient consent. Jay Cutler, J.D., special counsel and director of APA’s Division of Government Relations, stated in a December 27 letter to the editor of the New York Times that “APA is deeply concerned about a little-noticed fundraising loophole in the medical privacy rules. . . .”

For example, foundations affiliated with hospitals can have continued access to personal health information including a patient’s name, address, age, and telephone number without an individual’s consent. This can be especially damaging for psychiatric patients, said Cutler.

“In keeping with the spirit of the regulation, the first step should be to obtain a patient’s consent to release his or her name rather than releasing the name first and then allowing a patient to opt out as the rules state.

“Clearly, when it comes to massive government regulations, the devil is in the details,” concluded Cutler in the letter.

A marketing loophole in the final rules also allows physicians, hospitals, other health services, and their business associates working under contract with them to disclose patient health information under certain conditions: the products and services being marketed are of nominal value; are provided by the provider, the health plan, or a related third party; or the patient is solicited face to face, according to Nancy Trenti, an associate director in APA’s Division of Government Relations.

For example, a patient who has been treated for sexually transmitted diseases could receive telemarketing calls offering condoms or new medicines, according to a January 16 article in the Washington Post.

APA is also disappointed that the final rules do not require an independent judge to review whether a patient’s records should be released in civil, criminal, or administrative proceedings, said Trenti.

Burdensome Costs

The administrative and financial burden on physicians of implementing the new privacy regulations is increased by requiring them to ensure that any “business associate” who uses or discloses information about their patients complies with the privacy provisions, according to Trenti.

The Small Business Administration (SBA) estimates that physician practices will have to spend about $3,703 each in the first year to implement the new privacy rules. The annual cost then drops to about $2,806 per physician practice for the next nine years.

The penalties for noncompliance are stiff. Civil fines start at $100 per person for unintentional disclosures, with a maximum of $25,000 annually. Disclosure with the intent to sell personal health information is punishable by a fine of up to $250,000 and 10 years in prison.

APA continues to call on Congress to enact stronger privacy legislation to fill in the gaps in the final rules and give patients a right to sue for the abuse and misuse of their private health information.

Moreover, APA, the AMA, and health care organizations have complained loudly about the anticipated cost burden to the Department of Health and Human Services, which issued the regulation.

“The Bush administration may be sympathetic to reviewing and amending the provisions that increase administrative costs to health care providers,” according to Appelbaum.

The Final Standards of Privacy for Individually Identifiable Health Information are available on APA’s Web site at www.psych.org/pub_pol_adv/privacy122100.pdf. ▪