Jury Still Out on Impact Of Genes on Trial Verdicts

“My genes made me do it.”

Americans should not be surprised to hear that claim made by criminal defendants as the genetics of behavior, especially antisocial behavior, are explored by science and popularized.

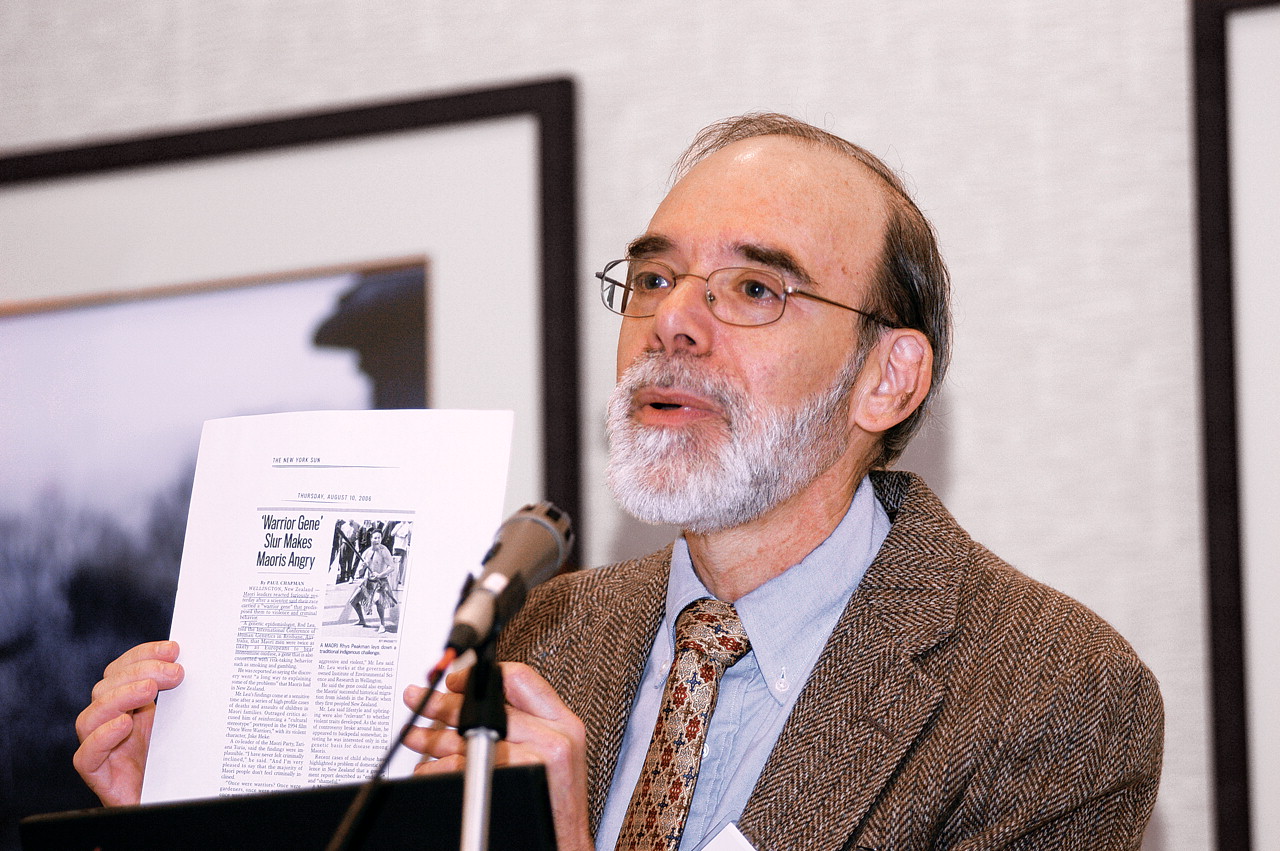

Paul Appelbaum, M.D., chair of APA's Council on Psychiatry and Law, told psychiatrists at APA's 58th Institute on Psychiatric Services last month that the findings of behavioral genetics—even such preliminary findings as have been made to date— are making their way into the American legal system.

He predicted, however, that genetic arguments are not likely to be successful in freeing defendants from guilt for their crimes, but may more likely be advanced in criminal cases as mitigating factors that should be taken into account in sentencing. Yet even there it remains to be seen how a genetic propensity will be viewed by juries and judges; such evidence could just as conceivably be seized upon as an argument against a defendant, Appelbaum said.

“If effective treatment becomes available, the pressure to identify [at-risk individuals] through screening at birth may be irresistible.”

Still, the groundwork for the logic of a genetic defense, in the form of the insanity defense, has already been laid by centuries of case law.

“Anglo-American law has created categories to excuse defendants from culpability when their capacity to choose their behavior is significantly impaired,” Appelbaum said. “If mental disorders that impair appreciation of wrongfulness or ability to control behavior negate culpability, why shouldn't genetic determinants have the same effect?

“Why should there not be a defense of genetic determinism, a `my genes made me do it' defense? The logic [of moving] from the existing insanity defense to such an argument is not so absurd that it has not already begun to make an appearance in our courts.”

Linking MAOA and Violence

Already rippling through the legal system with intriguing implications is a landmark study by Avshalom Caspi, Ph.D., and colleagues that appeared in Science in 2002 demonstrating a remarkable interaction between a specific genetic configuration and early childhood experiences in the development of antisocial disorder.

Drawing on a sample of more than 400 males in Dunedin, New Zealand, who had been followed since childhood for 26 years, Caspi and colleagues were able to examine the levels of monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) activity in those who did and did not exhibit antisocial behavior, including violence, in later years.

MAOA is an enzyme that sits on mitochondrial membranes in neurons and degrades several important neurotransmitters, including several believed to be important in the regulation of aggression and impulsivity. Previous animal research had shown that the absence of MAOA was associated with increased aggression. Levels of MAOA activity differ based on variation in the“ promoter region” of the MAOA gene, which controls the transcription of the DNA into messenger RNA.

Caspi and colleagues found from their longitudinal work with the Dunedin sample that low MAOA activity was not itself predictive, but that low MAOA activity in combination with a history of child abuse or neglect was predictive of antisocial behavior, including violence. Individuals with low MAOA activity and severe maltreatment comprised just 12 percent of the sample, but they accounted for 44 percent of the violent crimes committed by the sample.

“This quickly led to a lot of speculation about what this all might mean in terms of prevention of crime,” Appelbaum said. “Within a year of Caspi, the law reviews were discussing the impact of this study on criminal behavior. The legal system is paying attention, and we ought to be paying attention as well.”

Courts May Be Skeptical

Despite the excitement created by the Caspi study, Appelbaum said he believes that genetic propensities for violence will not be successful in excusing defendants from guilt.

He cited very early efforts to introduce genetic arguments as exculpatory factors that laid down a foundation for the courts' skepticism. In the early 1970s it was postulated that individuals with an extra Y chromosome were at increased risk for violence; several defendants tried to negate charges against them by introducing evidence of their XYY genetic type.

The courts were not receptive. Some refused to go beyond the insanity defense— if a defendant could not be proven insane, they weren't interested in genetics. Others insisted on demonstration of a more positive connection between violence and the genetic mutation, while others said that scientific evidence was insufficient—a prescient stand as the association between XYY and violence was later debunked.

Moreover, Appelbaum said, studies in behavioral genetics such as the Caspi report do not indicate a one-to-one causal relationship between a genetic mutation and a predilection for violence, leaving a statistical loophole, as it were, for the operation of personal choice in a decision to commit crime.

“The courts are going to be asking for a link that [lawyers] will have difficulty establishing since choice always seems possible, and the behavior is not completely determined,” Appelbaum said.

Paul Appelbaum, M.D., chair of APA's Council on Psychiatry and Law and a former APA president, says that the pressure to screen individuals for a genetic disposition to violence is likely to increase if interventions are identified that can reduce crime. Ellen Dallager

More likely, he said, lawyers will introduce genetic evidence as mitigating factors at sentencing.

“The argument would be that the defendant's capacity to choose to commit a crime is impaired even if it is not negated by a genetic predisposition, and that that ought to be something to think about when determining how long to lock him away,” he said. “This might be akin to a diminished-responsibility claim.”

He added that forensic experts from Tennessee who say they have routinely been doing MAOA genetic testing in the Tennessee courts would be presenting at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. (This meeting was being held in Chicago as this issue went to press).

“That is an indication that this is not esoteric theory limited to law reviews, but is being rolled out in our courts today,” Appelbaum said.

Medicalizing Social Problems?

Whether a genetic predisposition to violence should be mitigating is highly debatable, Appelbaum said, and it raises the potential for further medicalization of social problems—as in the case of sexual predators who are remanded to “treatment” following their prison sentences— for which there may or may not be reliable therapies.

“Unlike mental illnesses, genetic propensities are not treatable,” he said. “If you have low MAOA promoter activity, we don't know anything to increase it, nor is it clear that if we increased it in adulthood, it would compensate for maltreatment as a child.”

Moreover, the issue exposes what Appelbaum called “the double-edged sword” of behavioral genetics: the same evidence of a genetic propensity to crime could be seized upon to argue for harsher punishment.

“You are identifying a group of people who are at an increased risk for violence,” he said. “The argument that someone has a genetic propensity and is therefore prone to recidivism is liable to be an odd basis for leniency. Could it also be introduced as aggravating evidence? Should the prosecution be allowed to get [the genetic information] if the defense doesn't? And what if the State already had a sample that could be tested?”

A host of similarly vexing questions surrounds the potential use of behavioral genetics to predict and prevent crime. For instance, screening of children in abusive households has already been recommended in some quarters; if low MAOA activity is detected, it might serve as an argument for removing children from their homes.

But Appelbaum cautioned that there is no way of knowing whether such early intervention in instances of abuse actually makes any difference in averting later violence and antisocial behavior.

Also, screening of children will almost certainly raise the standard concerns about labeling them. “We will be creating a class of kids who are labeled as high risk for violence,” he said. “That can have really untold consequences ranging from negative decisions about placement and effects on self-image and behavior.

“What are the consequences for being told that you can't control your own behavior? Yet the pressure to screen is likely to increase if intervention can be shown to actually reduce crime. If effective treatment becomes available, the pressure to identify [at-risk individuals] through screening at birth may be irresistible.” ▪