Public, MH Strategies Benefit From N.Y. Merger

“There is no health without mental health.” —Former U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher, M.D.

That statement has guided a pioneering integration of mental health and public health in New York City and a remarkable exercise in population-based strategic planning targeting mental health and substance abuse problems.

Lloyd Sederer, M.D., executive deputy commissioner of mental hygiene services in the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, described the city's endeavors at last month's Institute on Psychiatric Services in New York.

Lloyd Sederer, M.D., executive deputy commissioner of mental hygiene services in New York City, describes innovative strategies to integrate mental health and public health. Sederer spoke last month at APA's Institute on Psychiatric Services. See page 11.

Ellen Dallager

Sederer detailed a range of population-based strategies targeting four broad public health areas—depression screening and treatment, screening and intervention for substance abuse, expansion of supportive housing, and focus on quality improvement on the part of community-based agencies funded by the department.

The strategies are part of an effort to integrate mental health and public health that began with the merger of the public health and mental hygiene departments in 2002. That merger has allowed the same kind of population-based approaches to be applied to mental health and substance abuse that are typically applied to health problems such as SARS, avian flu, or contaminated food, he said.

“The same understanding that there are diseases inherent to a population and preventive-intervention strategies that can make a difference to a population hasn't been well developed and hasn't been part of the identity of a [mental health] agency,” he said. “But we decided that we should be doing that.”

Under Sederer's leadership, the department is responsible for planning, purchasing, and monitoring quality control of public mental health services, oversight of population-based mental health interventions, and advocacy. The department funds 1,500 programs and 365 agencies serving 500,000 people, with an annual budget of $825 million.

Before taking on the position in New York, Sederer was director of APA's Division of Clinical Services from 2001 to 2003.

Screening a Key Element

A signature aspect of the initiative described by Sederer is the use of instruments to screen for depression in primary care settings and for substance abuse in Emergency Departments (EDs). This is part of an encompassing health policy in the city known as Take Care New York (TCNY).

“This is a health policy that addresses preventable causes of illness and death and focuses on underserved communities with a disproportionately high disease burden,” he said.

TCNY's 10 target intervention goals include the following:

Have a regular doctor or other health care professional | |||||

Be tobacco free | |||||

Keep Your heart healthy | |||||

Know your HIV status | |||||

Get help for depression | |||||

Live free of dependence on alcohol and drugs | |||||

Get checked for cancer | |||||

Get the immunizations you need | |||||

Make your home safe and healthy | |||||

Have a healthy baby | |||||

According to the New York City Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, only 37 percent of New Yorkers with depression report receiving mental health treatment, and only 26 percent of African Americans and 27 percent of Hispanics with depression are in treatment. These figures compare with nearly half (49 percent) of white people who receive needed treatment for depression.

“If you want to do something [in public health], you have to go where the people are,” Sederer said. “So we decided that we needed to go to primary care. Depression is more common than every other condition seen in primary care. And what we see are two principal patterns—either people don't go to get treatment or they go for one visit. So we know we have this dataset that makes for a chilling picture of a public mental health crisis. We have a highly prevalent yet treatable disease, but about 4 in 10 of those with depression don't get treatment, and 1 in 8 is getting minimally adequate treatment. This situation would never be allowed if we were talking about tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, or diabetes. Why should it be allowed for depression?”

Reaching the Tipping Point

What was missing, Sederer said, was an easy-to-use instrument for ascertaining depression severity in the primary care setting. The instrument that was chosen to fill the gap was the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).

One PHQ-9 question, for example, asks the respondent how often he or she has experienced nine symptoms of depression in the prior two weeks, including having little interest in activities; feeling down, depressed, or hopeless; or having trouble sleeping. Respondents choose one of four choices: not at all, several days, more than half the days, or nearly every day.

A second question asks respondents to rate how difficult these problems have made it to do work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people. Response choices are not at all difficult, somewhat difficult, or extremely difficult.

The instrument also includes a treatment algorithm that outlines treatment options ranging from self-management techniques taught by the primary care physician to specialty referral for more severe or refractory cases (Psychiatric News, May 20, 2005).

“We have worked to make this screening a required field in the electronic medical record throughout all the primary care practices in the Health and Hospitals Corporation,” he said. “That rollout will be complete by the end of this year, and that will get us screening 16 percent of all New Yorkers. We are going to keep this march going until at a certain point we are going to hit the tipping point.”

At that point, Sederer believes, the popularity of the screening—supplemented by the fear of liability for practices that don't screen—will quickly cause the PHQ-9 to become a standard of care.

Detecting Substance Abuse

Similarly, the city has sought to address substance abuse and alcoholism through widespread population-based screening at the point in the health care system at which much substance abuse makes itself felt—in the city's emergency departments.

To do this, Sederer said the agency has implemented Screening, Brief Intervention, Referral, and Treatment (SBIRT), an evidence-based program that emergency department and other medical staff can use to detect problem drinking or drug use and then provide a brief intervention. SBIRT is designed to reach people at a “teachable moment,” immediately following some traumatic consequence of their substance abuse, when they are most likely to be receptive.

“If you reach people after a bad consequence of their disease—in the ER or the trauma center or in a primary care setting, their defensive state is reduced,” Sederer said. “This intervention borrows on all the authority of the doctor or nurse to engage people in terms of recognizing the consequences of their substance abuse and taking responsibility at a point where they are much more apt to do so.”

Through collaboration with the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, Sederer's department has given funds to five hospitals to implement SBIRT in their EDs, has trained more than 300 ED clinicians, and is linking with hospital chemical-dependency programs and training primary care physicians to use the intervention.

There's No Chance Without Housing

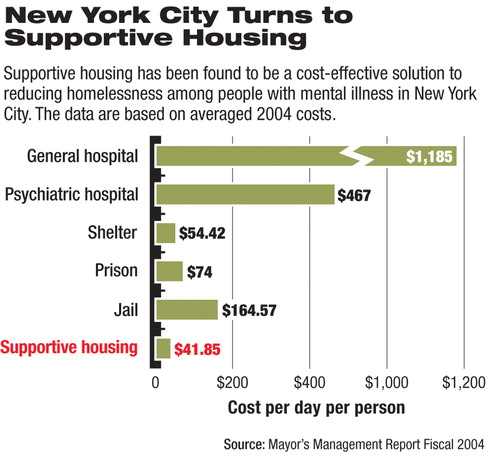

A third strategy the department is pursuing is to expand supportive housing for the city's mentally ill population. “We took the position that nobody stands a chance of recovering from these conditions unless they are safely and reliably housed,” Sederer said.

He said the agency managed to “pull off an incredible deal” to build 9,000 additional units of supportive housing, almost doubling the existing supply of housing for people with severe and persistent mental illness in New York City.

The success of the effort was driven not only by the all-too-obvious excess of people living on the streets, he said, but also by the proven cost-effectiveness of supportive housing (see chart).

“This is a compelling part of effective advocacy,” Sederer said. “You have to make three arguments—a moral argument, a clinical argument, and the economic argument. If you've got all three, you stand a chance.”

Finally, Sederer said the department has sought to introduce evidence of a process of quality improvement as a contractual requirement for all funded agencies in a program. Four key areas were identified as part of the Quality Impact program: consumer perceptions of care, screening for and treatment of co-occurring mental disabilities and disorders, cultural competence, and becoming a “welcoming clinic.”

Sederer said the goal was to make quality improvement a standard of doing business with the agency in the same way that the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations has made quality improvement a standard for hospitals.

“But when we looked at 100 of our community-based agencies, virtually none of them did this. This was an opportunity to introduce a method for training people to think about problems in a systematic way across the mental health system in the city.”

Despite some initial resistance, Sederer said, “most of the really good agencies found it was a way to improve their staff's professionalism, to improve their performance, and to illustrate what they are doing to their boards. They found that there were a lot of positive benefits.”▪