Boston Continues to Heal as Marathon Bomber Convicted

Abstract

The deadly Boston Marathon bombing in 2013 resulted in the implementation of both short-term and ongoing mental health responses.

Brent Forester, M.D., had two goals as the 2013 Boston marathon approached: breaking the four-hour mark for the 26.2-mile run and raising money for Alzheimer’s disease research.

“The Boston Marathon was always important to the city, and now its importance is ratcheted up,” said psychiatrist Brent Forester, M.D. “My guess is the race will never be the same.”

When he hit the finish line, all was well. His time was 3:58:51, and he had secured $12,000 for the Alzheimer’s Association.

But that was forgotten barely a minute later when he heard the first of two explosions and saw smoke and debris billowing behind him.

Two years later, the bombs that left three people dead and 257 injured remain an inescapable part of life in New England. A jury on April 8 convicted Dzhokhar Tsarnaev on 30 counts related to the crime.

During the month-long trial, surviving victims told their stories in graphic detail, reawakening memories of the bombing and its aftermath, said Forester, a geriatric psychiatrist at McLean Hospital and an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

Much of the story of the recovery from that terrible April 15 began within minutes after the bombs blasted chunks of metal through flesh and bone at the peak of Boston’s most symbolic civic moment. Medical and mental health personnel in the city had prepared for such an eventuality, recalled Frederick Stoddard, M.D., a psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital and a clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

“The response was one of the best by the health care system to a disaster, because the region’s hospitals and other services had trained extensively beforehand,” said Stoddard, coauthor of Disaster Psychiatry: Readiness, Evaluation, and Treatment (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2011), in an interview with Psychiatric News. “Earlier drills did not go well, but after the latest training prior to the marathon, systems for triage and communication were ready.”

“Having the trial of the bomber at this point is a stressor because the marathon is coming up again,” said Frederick Stoddard, M.D.

“Boston Strong” soon became the rallying cry for a city unintimidated by terror. The longer-term story of recovery reveals the spectrum of resources available in the region.

Many people affected by the event no doubt sought help privately from mental health professionals. Many others turned to the Massachusetts Resiliency Center, created by the state’s Office of Victim Assistance in July 2014 and paid for by a two-year grant from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Anti-Terrorism Emergency Assistance Program.

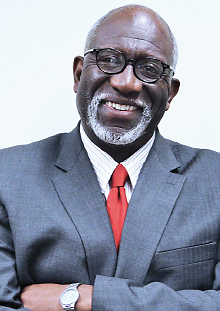

“We are a hub for services, not just providing them ourselves, but coordinating with other agencies,” Executive Director Kermit Crawford, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at Boston University Medical Campus, told Psychiatric News. “We’re helping normal people dealing with abnormal circumstances that disrupt daily functioning.”

Crawford, trained as a forensic psychologist, was no stranger to post-disaster mental health. One of the planes used in the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks had flown out of Boston. Crawford was called to Logan Airport and directed the behavioral health unit of the family-assistance center there. He subsequently did a variety of mental health consulting, evaluation, and training work after hurricanes Katrina and Rita.

“The Oklahoma City bombing showed us that the real manifestation of psychological and emotional problems may not arise for years,” said Massachusetts Resiliency Center Executive Director Kermit Crawford, Ph.D.

Last summer, he was named executive director of the Massachusetts Resiliency Center, which addresses not only mental health issues but also matters relating to employment, compensation, medical services, brain injury, hearing loss, caregiver and peer support, and legal services—all of which can affect victims or their survivors. The center has only six full-time employees and primarily works by contracting with clinicians and other collaborating groups.

As the trial of accused bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev opened March 4, the center also placed clinicians and patient navigators in the court building to be a resource for survivors or family members who chose to attend.

“Some people need long-term help, but most do not,” said Crawford. “You have to get back to a new normal. Life will not be the same after what many of us have gone through.”

Federal funding will end in July 2016, he said, but the center has a sustainability plan to allow it to continue providing services needed to move people along the way to recovery.

That continuing need is to be expected, said Forester. “As a psychiatrist, I understand that reactions to trauma may not occur right away but often come out months or years later,” he said. “It’s important to get that message out.”

Another important message is the need for repeated disaster response training, integrated with other emergency services, said Todd Holzman, M.D., co-chair with Stoddard of the Massachusetts Psychiatric Society’s Disaster Committee.

“We all know each other through these drills so that we can respond with people we know and trust,” he said. He endorses Stoddard’s proposals for training sessions in disaster psychiatry at APA meetings. “You never know when you’re going to need it.”

And perhaps others can learn from Boston’s experience. “Whenever a great evil is done, it has often led to a greater good, and we want to be part of that greater good,” said Crawford. “We want our work to become a model for disaster response.” ■