Gabbard Describes Possibilities, Perils for Aging Physicians

Abstract

Aging and retirement can be a rich period of harvesting the fruits of a busy career, mentoring young people, and cultivating new interests.

The qualities that make for an excellent physician—compulsiveness, perfectionism, and an exaggerated sense of responsibility for one’s patients—can also be the qualities that will make slowing down or retiring difficult or impossible.

But retirement, or semi-retirement, can also be a rich time of finding new directions and enjoying long-deferred pleasurable pursuits.

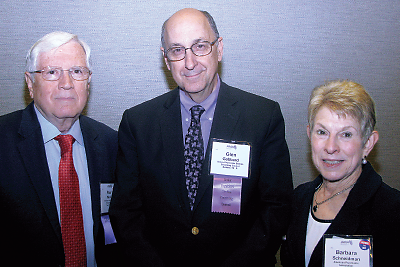

Psychiatrist Glen Gabbard, M.D. (center), stands with fellow psychiatrists Paul Wick, M.D., then chair of the Senior Physicians Section, and Barbara Schneidman, M.D., who was program chair of the Senior Physicians Section. Schneidman is now chair-elect of the section.

So said psychiatrist Glen Gabbard, M.D., in an address at last month’s meeting of the AMA House of Delegates. His talk, sponsored by the Senior Physicians Section (SPS), was followed by a discussion led by a panel that included child psychiatrist Louis J. Kraus, M.D., chair-elect of the AMA Council on Science and Public Health; David J. Welsh, M.D., vice chair of the AMA Organized Medical Staff Section; and Lt. Col. Ronit B. Katz, chair of the International Medical Graduates Section.

(The SPS also authored a resolution that resulted in the AMA Council on Medical Education’s report “Assuring Safe and Effective Care for Patients by Senior/Late Career Physicians”; see box).

“For most of us, the practice of medicine is not a job, it’s more of a calling,” Gabbard said. “I think that is one of the things that is quite unique about physicians—our identity is so much wrapped up in being a physician. So slowing down is often equated with losing one’s sense of self.”

AMA Approves Report on Assessing Late-Career M.D.s

AMA delegates approved the Council on Medical Education’s report titled “Assuring Safe and Effective Care for Patients by Senior/Late-Career Physicians.” The report was in response to a resolution brought to the House of Delegates by the Senior Physicians Section (SPS).

The report states that “[P]hysicians should be allowed to remain in practice as long as patient safety is not endangered and that, if needed, remediation should be a supportive, ongoing, and proactive process. … [P]hysicians must develop guidelines/standards for monitoring and assessing both their own and their colleagues’ competency. Formal guidelines on the timing and content of testing of competence may be appropriate and may head off a call for mandatory retirement ages or imposition of guidelines by others.”

Recommendations in the report call on the AMA to take the following actions:

Identify organizations that should participate in the development of guidelines and methods of screening and assessment to assure that aging/late-career physicians remain able to provide safe and effective care for patients.

Convene organizations identified by the AMA to work together to develop preliminary guidelines for assessment of the senior/late-career physician and develop a research agenda that could guide those interested in this field and serve as the basis for guidelines more grounded in research findings.

“Scientific data show that there are definitely cognitive changes as we get older,” said SPS member Claire V. Wolfe, M.D. “Whether those changes significantly affect performance is the issue, as is the means to identify individuals who may have significant changes. Self-recognition of cognitive loss doesn’t happen—people do not recognize when they are experiencing significant cognitive loss. We need guidelines to assess our colleagues in a collegial, nonpunitive manner, and we think the AMA is the right organization to convene groups to do that.”

Psychiatrist Barbara Schneidman, M.D., who is chair-elect of the SPS, said APA would like to be involved in a multidisciplinary group to develop guidelines and best practices for assessing competency of late-career physicians.

He recalled a retired physician who told him, “Glen, don’t ever give up your license. I gave up mine six months ago, and all I can think about now is blowing my brains out. Everything in my whole life has been about medicine.”

“That’s an extreme example of something that I think is quite common among physicians, which is that we can very easily lose track of our purpose if we aren’t doing what we love to do,” Gabbard said. (Gabbard said the physician was referred to a psychiatrist and treated for depression; he also got his license back and began working at a free clinic for indigent patients.)

“It is the profound gratifications that medicine offers that make aging a challenge,” Gabbard said. “The psychological characteristics that make for a good physician also make it hard to stop working. We have a need to be needed.”

A renowned psychoanalyst and a popular speaker at APA meetings, Gabbard has made a specialty of sorts treating physicians. He is director of the Gabbard Center, a multidisciplinary outpatient psychiatric evaluation center in Houston. The center provides evaluations of any adult with complicated diagnostic or treatment problems but specializes in evaluating physicians, clergy, attorneys, executives, and professional athletes, often referred by licensing boards, physicians’ health organizations, medical schools, residency training programs, professional ethics committees, and hospitals.

He described a “triad of compulsiveness” including doubt, guilt, and an exaggerated sense of responsibility that characterize many physicians. The result is a driven perfectionism that can make for an excellent physician, but that is in fact maladaptive. “Despite cultural sanctions, perfectionism is not adaptive,” Gabbard said. “Perfectionism is a vulnerability factor for depression, burnout, suicide, and anxiety.”

But aging can also be a period of great possibility, rather than peril, for physicians who seize on this inevitable phase in their life with a positive attitude. Gabbard cited a recent survey (appearing in Mayo Clinic Proceedings) of 7,288 U.S. physicians regarding work lives, satisfaction, and burnout among early- , middle- , and late-career groups that found that late-career physicians were the most satisfied and had the lowest rates of distress.

“Whether you retire or not, make time for living,” Gabbard advised. He quoted William Saroyan, who said “ ‘In the time of your life, live.’ Don’t postpone—the 60s and 70s are time for harvesting—spend money on those things you have postponed.

“Retirement should not be about leaving something; it should be about going to something,” Gabbard said. “Whether you work part time, not at all, or full time, have a plan about what gives you joy. You have nothing to prove—you have run the race and are no longer in competition.” ■