Some Hypertension Medications May Protect Against Depression

Abstract

An analysis of Danish health registry data finds none of the 41 commonly used antihypertensives to be associated with depression risk, while nine are potentially associated with reduced depression incidence.

Clinical studies have shown that nearly 1 in 3 people with hypertension or related cardiovascular problems also has depression. A study published in Hypertension now suggests that several common antihypertensive medications may help reduce the risk of depression.

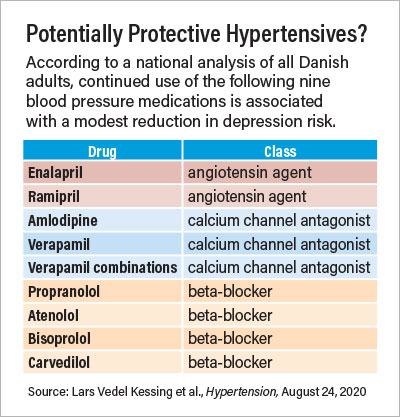

The medications that were found to protect against depression include two angiotensin agents (enalapril and ramipril), three calcium channel blockers (amlodipine, verapamil, and verapamil combinations), and four beta-blockers (propranolol, atenolol, bisoprolol, and carvedilol). Diuretics, the fourth commonly used class of antihypertensives, were not associated with any reduced risk of depression.

These findings come from an analysis of Danish health registry data by researchers at the University of Copenhagen and colleagues. The group calculated the incidence rate of depression among all Danish adults with no prior history of depression between 2005 and 2015. They used two definitions of depression: a strict criterion to include only adults who received a diagnosis from a psychiatrist, and a broader definition that included adults who received a diagnosis from a psychiatrist or a prescription for an antidepressant.

The researchers found that the adults who had never been prescribed an antihypertensive were 30% to 50% less likely to develop depression (depending on the class of hypertensive and definition of depression used) than those who had been prescribed the medications. Among adults who were prescribed antihypertensives, however, increased medication usage did not raise depression risk for any of the four drug classes tested; a person receiving 10 prescriptions of a beta-blocker was no more likely to develop depression than someone who only received one. Additionally, patients who continually used angiotensin agents, beta-blockers, and calcium channel blockers were less likely to develop depression compared with adults who received only one or two prescriptions.

The investigators next analyzed the 41 most prescribed medications in these three antihypertensive classes. Of these, the nine previously listed were associated with reduced depression under both the strict and broad definitions of depression. All nine are approved for use in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration.

Lead investigator Lars Vedel Kessing, M.D., D.M.Sc., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Copenhagen, told Psychiatric News that the nine drugs do not share any specific similarities that point to how they help reduce depression, but “so far the best explanation is they reduce inflammatory processes that connect cardiovascular disorders and depression.”

Given the dozens of available blood pressure medications to choose from, Kessing said these findings could help guide physicians when selecting a medication for a patient who has a family history of depression. This list could also be useful for patients with current depression who develop hypertension. He noted that the study looked at these medications as preventive measures, but drugs that protect against depression are likely to have positive effects on symptoms in people with existing depression.

“At the same time, if a person is doing well on a current prescription—even a diuretic—there is no need to switch medications,” he said.

“Even though this is an observational study that analyzes administrative data, these findings from a national population offer reassurance that none of the main classes of blood pressure medications pose depression risks,” said Lena Mathews, M.D., an assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

Mathews, who specializes in cardiology and epidemiology, noted that older research had suggested beta-blockers may increase the risk of depression because fatigue is a common side effect. She added that the possibility that some beta-blockers or other agents may even prevent depression is intriguing, but controlled clinical trials should be conducted to validate this hypothesis.

“This study supports the importance of addressing physical health problems in patients with mental disorders and is consistent with a large body of literature suggesting that effective medical treatment does not worsen mental health outcomes,” echoed Benjamin Druss, M.D., M.P.H., professor and the Rosalynn Carter Chair in Mental Health at Emory University Rollins School of Public Health.

Druss, who was not involved in this study, hopes it reinforces that psychiatrists should always be aware of all their patients’ mental, medical, and social issues.

“That last item is especially relevant for minority populations and people with low incomes, who have higher rates of both hypertension and depression, Mathews said. These groups also face more difficulties with access to health care and may have difficulty staying adherent to medications.

“Make sure to ask your patients what aspects of their situation may be preventing them from taking their medications and help them find a solution.”

This study was funded by the Danish National Research Fund. ■

“Antihypertensive Drugs and Risk of Depression: A Nationwide Population-Based Study” is posted here.