Nature, Nurture Both Contribute to Suicide Risk

Abstract

A large-scale analysis of suicide risk among different types of families also found evidence to suggest suicide attempts and completed suicides do not necessarily arise from the same genetic risk factors.

Numerous studies have suggested that suicidal behaviors can be passed down from generation to generation. An analysis of Swedish health and family registries now suggests genes and parental rearing contribute roughly equally to this risk.

Though not the first large-scale effort to understand the heritability of suicide risk, this latest study published in AJP in Advance might be the most comprehensive to date.

Investigators at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) in collaboration with a team at Lund University in Sweden compiled data from four types of family structures: a typical nuclear family, children raised entirely by single mothers, families with a stepfather (who raised the children for at least 10 years), and families with adopted children.

For the single mother and stepfather groups, the investigators included only families in which the biological father was deceased or lived far away to remove cases where a nonresiding father still might influence the child’s environment. (Single-father families in Sweden are quite rare and therefore were not included in the study; also, children living with second-degree relatives such as grandparents were excluded from the analysis.)

The final sample included more than 2.4 million Swedes who were born between 1960 and 1990. Among this group, 2.8% of those who lived in nuclear families attempted suicide at least once, compared with 6.3% of those living with single mothers, 5.5% living with stepfathers, and 6.7% living with adoptive parents. Corresponding rates of completed suicides for these four groups were 0.3%, 0.6%, 0.5%, and 1.0%, respectively.

When looking at the family history of suicide attempt among people who attempted suicide, the investigators found that genetic and environmental contributions were about the same.

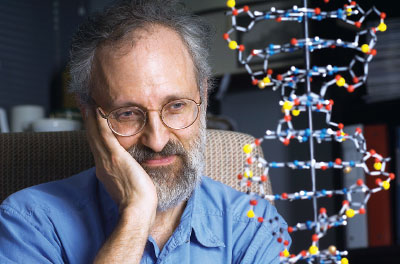

The strong influence of both genetics and rearing in suicide risk shown in this latest study reinforces that psychiatrists should consider full family histories even for patients raised by single or adoptive parents, says Kenneth Kendler, M.D.

“If I’m an adoptee and I have an adoptive parent who raised me who attempts suicide, and I had a biological parent who I’d never met who attempts suicide, they convey a virtually equal risk to me for a suicide attempt,” explained lead author Kenneth Kendler, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at VCU and director of the Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, in a press release.

Kendler and colleagues also estimated that in people who were exposed only to a genetic risk of suicide attempt, about 40% of that risk could be attributed to the parent having a mental illness or substance use disorder.

“There is a mindset in psychiatry that anything that runs in families does so via genetics,” Kendler told Psychiatric News. “Our findings reinforce that the way we rear our children matters.”

As a second objective, Kendler and his team also explored cross-transmission of suicide attempts—that is, how exposure to the death of a parent by suicide influenced suicide attempt in offspring, and how exposure to a suicide attempt in a parent influenced death by suicide in offspring. (They also looked at how suicide death in parents affected suicide death in offspring, but because these events were rare, they could not draw firm conclusions.)

People who had both biological and environmental exposure to a suicide death had the highest risk of a suicide attempt; likewise, those with both genetic and environmental exposure to a suicide attempt had higher risk of suicide death. However, among the various family types, the risks of an attempt after exposure to death and the risk of a death after an exposure to an attempt were not identical.

“What this tells us is that a suicide attempt and suicide completion are not two different outcomes arising from the same genetic risk,” Kendler said. “This makes sense, given the observations that nonfatal attempts are often more impulse-driven and use less lethal means [like pills] than completed suicides.”

As a large-scale genetic analysis, this current work will probably not move the needle on how psychiatrists manage potential suicide risk in patients, Kendler acknowledged. But he hopes that professionals remember that genes and rearing both play strong roles; for example, psychiatrists should pay close attention to family history of suicidal behaviors even when patients were raised by an adoptive family.

The study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health and the Swedish Research Council. ■

“The Sources of Parent-Child Transmission of Risk for Suicide Attempt and Deaths by Suicide in Swedish National Samples” is posted here.