Special Report: Guidance on Managing Side Effects of Psychotropics

Abstract

Managing adverse drug effects is always challenging, but can be especially so in patients with psychiatric disorders, for whom adherence may be precarious, tolerance for discomfort attenuated, and insight about the need for treatment tenuous.

Throughout medicine, treatment decisions involve the balancing of risks and benefits. Psychopharmacologists decide when and what medications are appropriate for a patient with a given clinical presentation, relative to the available alternatives. Those alternatives may include no treatment, watchful waiting, purely psychosocial or nonpharmacological interventions, and device-based treatments. How patients and clinicians anticipate the chances for incurring adverse drug effects and regard them as manageable versus “deal breaking” lies at the heart of clinical decision-making for most, if not all, clinical encounters.

As readers of this article know, drugs exert varied pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic effects that we interpret as beneficial or adverse. All drugs—even placebos—have the potential to cause undesired effects. Clinical wisdom in the risk-benefit analysis of psychotropic medications involves the interplay of many factors:

Judging likely cause and effect (or knowing when a physical complaint likely reflects an iatrogenic phenomenon versus a manifestation of untreated psychopathology).

Distinguishing transient from enduring adverse drug effects and treatment complications that are annoying but innocuous. Example: dry mouth, nausea, headache, sexual dysfunction, etc., versus a medically hazardous condition (such as serotonin syndrome, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, severe cutaneous reactions, and torsade de pointes) versus conditions with intermediate but manageable levels of medical risk (such as orthostatic hypotension, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, moderate weight gain, and glycemic dysregulation).

Recognizing possible pharmacokinetic factors that can mediate drug response. Example: compensating for known drug-drug interactions, such as when pairing lamotrigine with divalproex or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) that inhibits the metabolism of a co-prescribed tricyclic antidepressant.

Recognizing opportunities to exploit and capitalize on a desirable side effect. Examples: appetite suppression from psychostimulants or pro-anorexic anticonvulsants such as topiramate or zonisamide; the management of insomnia through the sedative or soporific effects of antihistaminergic antidepressants.

Knowing when fairly simple antidote strategies can likely eliminate an adverse effect. Example: adding valbenazine or deutetrabenazine to a continued antipsychotic drug in the presence of tardive dyskinesia.

Knowing when to forego possible efficacy over safety when viable alternative treatment options exist. Examples: favoring divalproex or carbamazepine over lithium when the patient’s creatinine level is steadily rising; choosing not to rechallenge a patient with clozapine after recovery from iatrogenic myocarditis.

Identifying confounding factors that can amplify risk for an adverse drug effect. Examples: eliminating alcohol or sedative hypnotics to allow better tolerability of a core psychotropic drug with intrinsic sedative properties; in patients taking a second-generation antipsychotic, minimizing substances or medications that pose additive risk for QTc prolongation (such as alcohol, ondansetron, antifungal agents, cyclobenzaprine, trazodone, vardenafil, or valbenazine).

Knowing when drugs that exert large or unique effects are not readily replaceable by more “innocuous” alternatives; increasing the importance for devising strategies to mitigate adverse effects that can be managed.

Knowing when and how the potential gains of a higher “risk” drug can be tactically managed.

One of the greatest challenges in psychopharmacology involves teasing apart complaints that reflect true iatrogenic phenomena from intrinsic, ongoing manifestations of the ailment being treated. Important examples include the intensification of suicidality in a depressed patient taking an antidepressant or anticonvulsant, alleged “worsening” of psychosis during antipsychotic pharmacotherapy, and the emergence of mania or hypomania in a bipolar patient taking an antidepressant. It is helpful to know risk factors for particular adverse effects to help distinguish probable iatrogenic events from simple lack of efficacy against the disorder being treated or from the vicissitudes of the natural course of illness. For example, true induction or intensification of suicidal thoughts or behaviors from antidepressants is more likely to occur in younger than older patients, those with concomitant substance use disorders, and those with more severe baseline depression. Antidepressants have a known but relatively low risk for acutely inducing mania (about 12% according to meta-analyses from prospective trials), one that is definably higher in distinct bipolar subgroups—namely, patients with bipolar I versus II, presentations involving mixed features rather than pure depressed phases of illness, a history of past-year rapid cycling, a history of antidepressant-associated mania, and possibly with the presence of the s/s genotype of the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4).

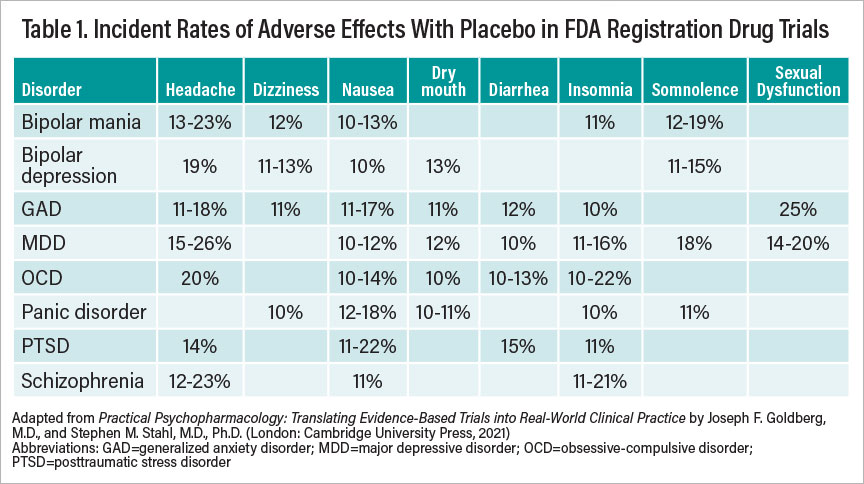

Table 1

Clinicians can readily consult the package insert information to identify the likelihood and probable incidence of a particular adverse effect relative to placebo. Much the way we compare drug versus placebo to determine efficacy, so too must we consider adverse drug effects relative to those reported for placebo to understand true pharmacodynamic consequences. The so-called nocebo phenomenon (that is, adverse effects from an inert substance) often reflects attitudes and expectations among patients (or prescribers) about the presumed tolerability of a given compound. Nocebo rates as reported across clinical trials may vary by disease states. For example, major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder are among the conditions most prone to nocebo effects overall, while attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bulimia are among the least. In clinical trials, akathisia has been reported to occur in up to a quarter of schizophrenia patients taking placebo. Surprisingly, among patients with generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder, adverse events from placebo in clinical trials are often lower than would be expected, and premature study discontinuation due to nocebo effects is rare. Table 1 presents a summary of commonly observed nocebo rates as reported across clinical trials in various psychiatric disorders.

Working With Patients on Side-Effect Complaints

A further common problem in clinical practice involves the emergence of unusual (though often innocuous) patient complaints and questions about whether or not a particular drug could cause a suspected idiosyncratic side effect. If one were to Google any paired combination of a random drug with a random physical complaint, there is a high probability of finding at least several hits. Drug package inserts report many dozens of possible adverse effects for innumerable psychotropic compounds that have been reported as infrequent (an incidence less than 1 in 100) or rare (an incidence between 1 in 100 and 1 in 1,000 cases). For example, laryngeal edema, esophageal ulcers, or purpura are rarely reported with fluoxetine; appendicitis, gout, or aortic aneurysms are reported rarely with venlafaxine.

How does one infer probable causality from other unrelated explanations, including random chance? Causal inferences often cannot be made from stray case reports or reported as curious “infrequent” or “rare” events in manufacturers’ product labeling because of the absence of denominators: Unless all exposed subjects have been prospectively and systematically assessed for the emergence of a given possible adverse effect, one cannot reliably discern the chances of a spontaneously occurring but pharmacologically unrelated event.

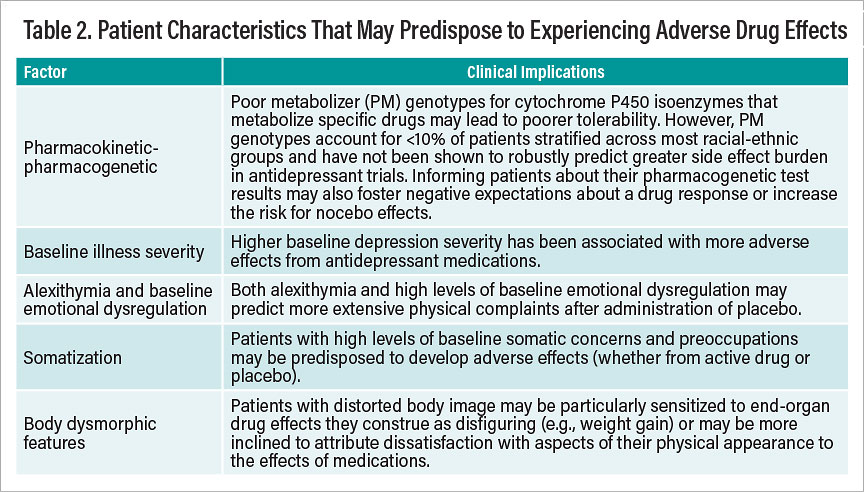

Table 2

Often, it is helpful to consider the plausibility of mechanisms of action when trying to gauge likely causal associations. For example, it is unusual for an anticholinergic drug to cause diarrhea or rhinorrhea, lithium to cause urinary retention, or amphetamine to cause sedation. Reports have surfaced in the literature claiming the occurrence of paradoxical adverse effects, such as mania allegedly induced by lithium or olanzapine, psychosis “worsened” by aripiprazole, depression “exacerbated” by antidepressants, and cognitive decline “precipitated” by donepezil. Likely causal associations may be more compelling when suspected “adverse effects” occur in an on-off-on exposure paradigm (that is, where the event of interest appears, then vanishes, and then reappears after reinitiation following drug cessation).

Of equal importance for careful assessment is the ability to recognize factors that may predispose certain patients to experience adverse drug effects—whether arising from pharmacodynamic/pharmacokinetic or nonpharmacodynamic causes. Known risk factors that can predispose particular patients to report adverse drug reactions or physical complaints in response to taking a prescribed drug are summarized in Table 2.

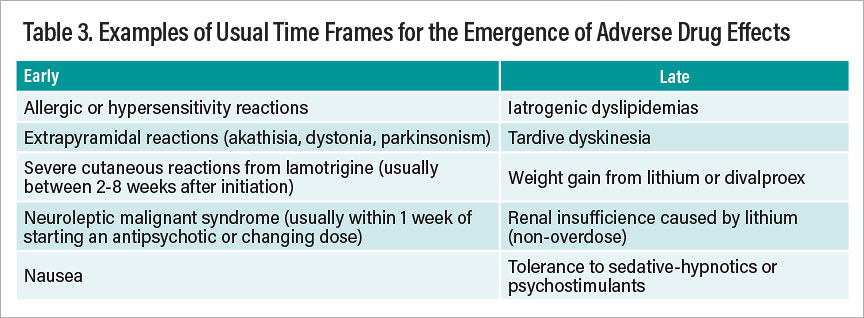

A further consideration involves recognizing the expectable time frames for the emergence of drug effects, whether desired or undesired. Much as we usually judge therapeutic effects of many psychotropic drugs using a fairly short-term time frame (perhaps four to six weeks), so too do most (but not all) side effects make themselves known sooner rather than later. Table 3 summarizes representative adverse effects that tend to occur early versus late in the course of treatment with psychotropic drugs.

Table 3

To paraphrase Sir Francis Bacon, nobody ever wants a remedy to be worse than the disease it treats. However, there is a delicate balance in distinguishing harm caused by an illness from possible iatrogenic harm. For conditions that inherently cause significant morbidity or mortality, there is little virtue in choosing medications that exert low effect sizes simply because they are perceived as having more modest adverse effects. For example, buspirone is widely regarded as a relatively safe and benign treatment option for anxiety, but its effect size in trials for generalized anxiety disorder is low. Similarly, lamotrigine may be desirable as a mood stabilizer at least in part because it requires no laboratory monitoring and has shown minimal differences from placebo in its adverse-effect profile when dosed properly, but it too has a relatively small effect size for the acute treatment of bipolar depression. Illness severity and the magnitude of expected drug effect sizes must be taken into account when deciding pharmacotherapies for each patient. In a patient with highly deteriorated or treatment-resistant chronic psychosis or a patient with schizophrenia at high suicide risk, there may be no viable alternatives to clozapine, and the use of simpler or “innocuous” treatments may come at the cost of markedly less efficacy.

Weighing and Managing Side Effects

Physicians and patients alike readily tend to prioritize drug efficacy over tolerability when both sides agree on the severity and gravity of a clinical problem. Moreover, psychiatrists often implicitly assess patients’ capacity to appreciate the nature and severity of their condition when proposing treatment options for which the prospect of adverse drug effects must be contextualized and reckoned with. Metastatic cancer or other life-threatening conditions typically prompt patients to seek more aggressive therapies when they perceive a higher likelihood for reducing the morbidity and possible mortality caused by a severe disease. Intact insight about the presence and severity of an illness is often a prerequisite for risk-benefit decision-making. Cancer patients seldom, if ever, ask their oncologists for an antineoplastic drug with fewer side effects when the mortality stakes appear glaring and there are few viable alternatives.

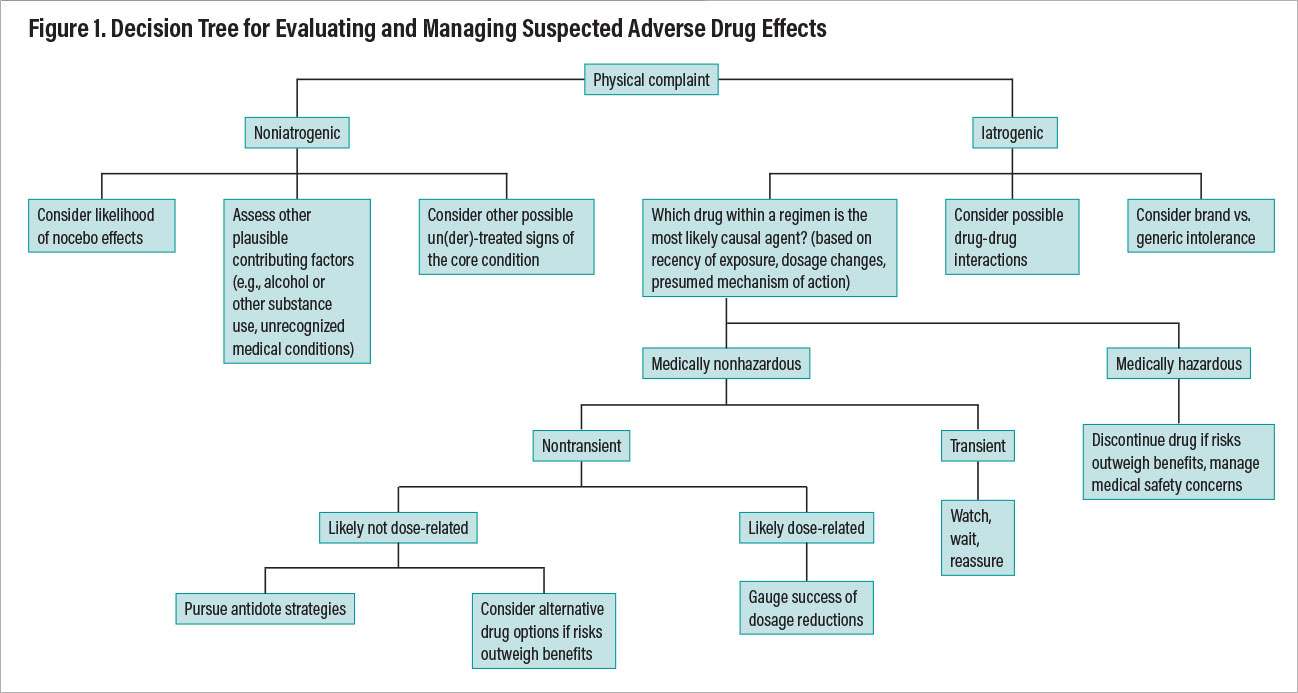

Figure 1

One approach to working with patients about taking “high risk/high yield” drugs for serious conditions may be to point out time frames for the use of a high-potency drug with substantial risk for undesired but imminently nonhazardous adverse effects such as weight gain. Consider instances in which one might wish to propose olanzapine-fluoxetine combination to patients with treatment-resistant depression; it is the only medication other than esketamine with FDA approval for such a purpose. Patients may demur based on concerns about the potential for weight gain. One might point out that the time frame for judging signs of responsivity (a few weeks) is much shorter than the time frame in which one might anticipate significant weight gain. If signs of an initial benefit occur, one then has the option to continue treatment and pursue possible antidote strategies (see Table 5) to offset psychotropic-induced weight gain if it occurs or to forego continued treatment, secure in the knowledge that proven efficacy is viable. And, if no initial signs of benefit emerge, the risk for later weight gain or other potential adverse effects becomes moot, and one might opt to move on to other treatment options.

Once the determination has been made that a physical complaint represents a likely true pharmacodynamic adverse effect, one must then clarify its medical seriousness, likely transience or persistence, dose relatedness, confounding factors such as unrecognized alcohol or substance use, the impact of nonpsychotropic medications or comorbid medical conditions, and manageability through mitigation strategies. Figure 1 provides a decision tree outlining a systematic approach to evaluating a patient’s physical complaint as a potential adverse effect (that is, an iatrogenic event) and ways of reasoning through optimal management.

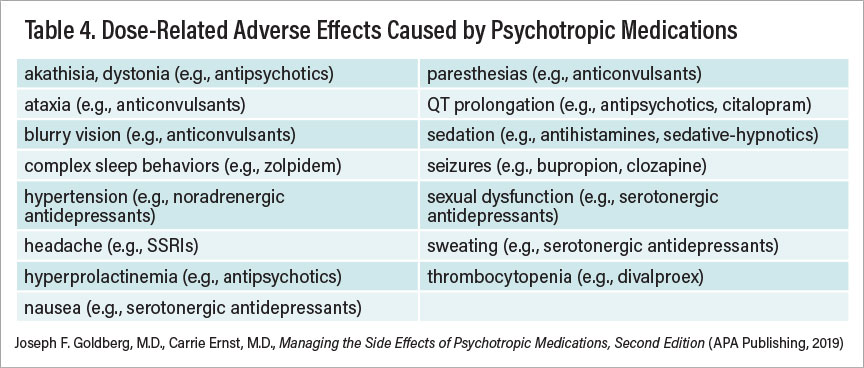

Table 4

Dosage reductions are sometimes (but not always) an initial fruitful approach to minimize certain adverse effects. Table 4 summarizes adverse effects that tend to be influenced by drug dosage.

Adding a medication to counteract the adverse effects of a therapeutic agent is common practice in oncology and infectious diseases. Antiemetic drugs are routinely prescribed to offset nausea caused by antineoplastic drugs; probiotics are used to replenish bacterial flora unintentionally disrupted by antibiotics, as are antifungal agents to counteract opportunistic candidiasis following antibiotic use. In psychiatry, patients may be hesitant about taking a psychotropic drug from the outset, and the seemingly mundane matter of adding an antidote drug may not always be met with enthusiasm. In some instances, adding a medication could provide ambivalent patients with a rationalization for poor adherence or treatment discontinuation. Wise clinicians present patients with a sense of agency about their own care by giving them options and spelling out the pros and cons for pursuing mitigation strategies for adverse effects.

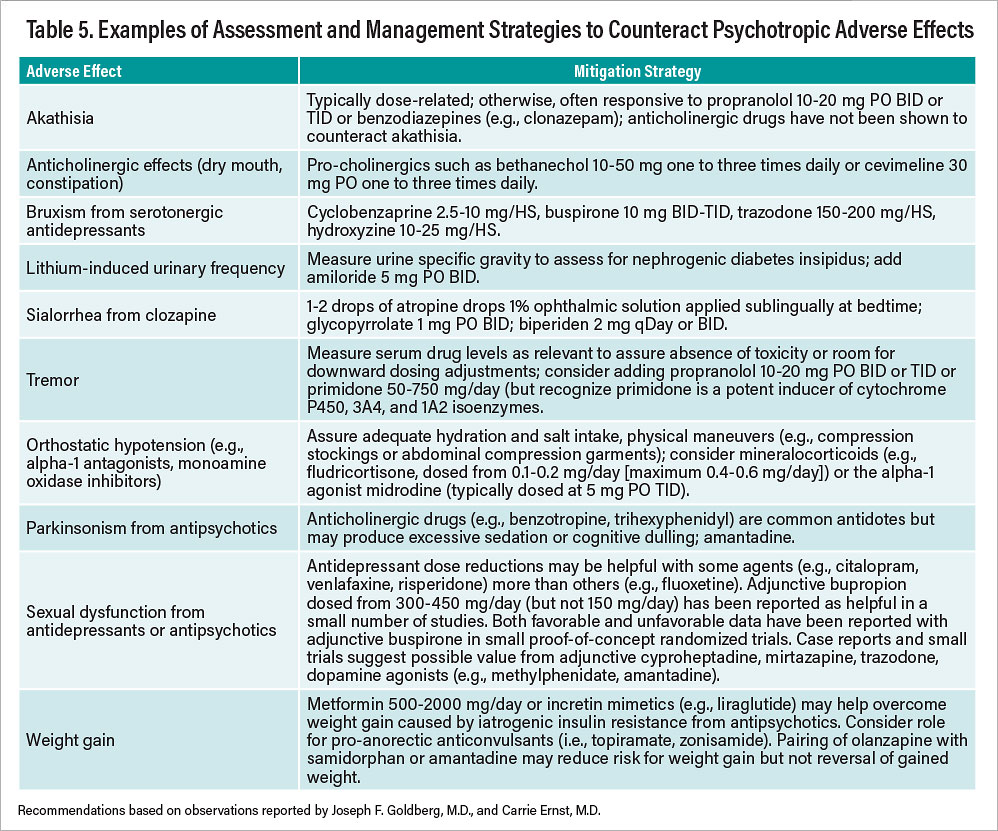

Table 5

Table 5 presents a summary of “antidote,” or management, strategies for commonly encountered, nonhazardous adverse effects from psychotropic drugs. Note that all interventions described involve the off-label use of other compounds; few, if any, have FDA approval for specific use to counteract adverse effects caused by another drug.

Adverse drug effects present inevitable challenges throughout all of medicine. They often require a particularly delicate touch with patients with psychiatric disorders, for whom adherence may be precarious, tolerance for physical or emotional discomfort may be attenuated, and insight about the need for treatment may be tenuous. Clinicians must recognize when benefits outweigh risks (particularly for conditions with high psychiatric morbidity/mortality), especially when a drug exerts unique benefits, and active management strategies can improve drug tolerability and safety. When risks outweigh benefits, alternative therapeutic strategies may be both viable and preferable.

Simultaneously, practitioners must remain attuned to surmountable ways in which patients may experience adverse effects as a potential threat to treatment adherence. Maintaining a strong therapeutic alliance is critical to foster shared decision-making, allowing patients and psychiatrists to collaboratively pursue mutually acceptable solutions without jeopardizing safety or the prospects for optimal therapeutic outcomes. ■

References

Goldberg JF, Ernst CL. Core Concepts Involving Adverse Psychotropic Drug Effects. Psychiatr Clin N Amer 2016; 39: 375-389.

Goldberg JF, Ernst CL. Managing the Side Effects of Psychotropic Medications, 2nd Edition. Washington DC: APA Publishing; 2019.

Fornaro M, Anastasia A, Novello S, et al. Incidence, Prevalence and Clinical Correlates of Antidepressant-Emergent Mania in Bipolar Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Bipolar Disord. 2018; 20: 195-227.

Goldberg JF. Determining Patient Candidacy for Antidepressant Use in Bipolar Disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 2019; 49: 386-391.

Goldberg JF, Stahl SM. Practical Psychopharmacology: Translating Evidence-Based Trials into Real-World Clinical Practice. London: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Yuvarajan R, Yousufzai NM. Mania Induced by Lithium Augmentation. A Case Report. Br J Psychiatry. 1988; 153: 828-830.

Reeves RR, McBride WA, Brannon GE. Olanzapine-Induced Mania. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1998; 98: 549-550

Takeuchi H, Remington G. A Systematic Review of Reported Cases Involving Psychotic Symptoms Worsened by Aripiprazole in Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder. Psychopharmacol (Berl). 228: 175-185.

Hakimi Y, Petitpain N, Pinzani V, et al. Paradoxical Adverse Drug Reactions: Descriptive Analysis of French Reports. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020; 76: 1169-1174.

Greden JF, Parikh SV, Rothschild AJ, et al. Impact of Pharmacogenomics on Clinical Outcomes in Major Depressive Disorder in The GUIDED Trial: A Large, Patient- and Rater-Blinded, Randomized, Controlled Study. J Psychiatr Res. 2019; 111: 59-67.

Haga SB, Warner LR, O’Daniel J. The Potential of a Placebo/Nocebo Effect in Pharmacogenetics. Public Health Genomics. 2009; 12: 158-162.

Demyttenaere K, Albert A, Mesters P, et al. What Happens With Adverse Events During 6 Months of Treatment With Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors? J Clin Psychiatry. 2005; 66: 859-863.

Hidalgo RB, Tupler LA, Davidson JR. An Effect-size Analysis of Pharmacological Treatments for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2007; 21: 864-872.

Selle V, Schalkwijk S, Vásquez GH, et al. Treatments for Acute Bipolar Depression: Meta-Analysis of Placebo-Controlled, Monotherapy Trials of Anticonvulsants, Lithium,and Antipsychotics. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2014; 47: 43-52.

Fiaschi MD, Voltolini S, Velotti P, et al. Nocebo Effect in Patients With Adverse Drug Reactions: The Role of Emotion Regulation. Mediterranean J Clin Psychol 2019; 7: 3.

Disclosure Statement

Dr. Goldberg is a consultant to BioXcel, Lundbeck, SAGE Therapeutics, MedScape, Otsuka, Psychiatry and Behavioral Health Learning Network, Sunovion, and WebMD. He serves on the speakers bureaus for Allergan, Intracellular Therapies, Otsuka, and Sunovion, and he receives royalties from American Psychiatric Association Publishing Inc. and Cambridge University Press.