To Minimize Medication Withdrawal, Taper Slowly

Abstract

After experiencing withdrawal symptoms while trying to wean himself off antidepressants, one doctor began questioning if traditional tapering protocols have it right.

A few years back, Mark Horowitz, M.D., wondered if the fatigue, memory, and concentration issues he had started to experience were due to his antidepressant therapy. He decided to wean off his medication, and as a doctor with psychiatric training, Horowitz decided he was comfortable handling the medication taper on his own. He knew the clinical consensus was that antidepressants could be tapered to zero over a period of about four weeks with minimal risk. To be extra cautious, Horowitz decided to taper his medication over four months. During this process, however, he became blindsided by insomnia, dizziness, anxiety, and panic attacks so severe and persistent that he had to go back to his original antidepressant dose.

After these symptoms subsided, Horowitz, who was then finishing his Ph.D. in neurobiology at the Institute of Psychiatry at King’s College London, became determined to find a better tapering strategy that minimizes both withdrawal symptoms and the risk of relapse.

“There is an urgent need to develop official guidelines for how to safely taper psychotropics”—for both patients and physicians, Horowitz said.

Rapid Discontinuation Increases Relapse Risk

As Horowitz began searching for information on how to taper antidepressants safely, he discovered that there was little scientific literature published on this subject. Some reports noted that abrupt discontinuation could lead to withdrawal symptoms, but it was generally regarded that a short tapering period would limit withdrawal effects and those that occurred would be transient. Any longer-lasting effects were simply attributed to a relapse of the patient’s depressive symptoms.

Turning to online support groups for people coming off antidepressants, Horowitz found numerous testimonials by people experiencing antidepressant withdrawal symptoms for weeks or even months after tapering their medications based on the recommendations of their doctors. These online groups also included testimonials by people who reported they had avoided withdrawal symptoms by reducing their dose by tiny amounts over a year or more (some of them going as far as buying jeweller’s scales so they could weigh out tiny fractions of pills).

Horowitz decided to reach out to David Taylor, Ph.D., one of his graduate school mentors. Taylor, a professor of psychopharmacology at King’s College London and director of pharmacy and pathology at the Maudsley Hospital, had done some research into withdrawal following antidepressant discontinuation. Taylor’s research of calls to a U.K. medication helpline in the late 1990s and early 2000s had revealed that the most frequent patient calls involved reports of severe withdrawal-like symptoms after stopping antidepressant therapy, including many instances of skin tingling or other sensory problems that were not related to depression.

Taylor and Horowitz believe that these types of symptoms arise when tapering antidepressants because traditional tapering protocols reduce the medication dose by fixed amounts (for example going down by 25% over four weeks), which is inconsistent with how psychotropic medications interact with their biological targets.

A review of pharmacological studies on antidepressant receptor binding (which all companies conduct as one of the first steps of psychiatric drug development) by the pair revealed that antidepressants can effectively bind to targets at low doses. For example, just 1 mg citalopram daily (a fraction of the typical starting dose for treating patients with depression) occupies over 20% of serotonin transporters in the brain; occupancy rises to nearly 60% at 5 mg daily and 80% at 20 mg daily (the typical starting dose of citalopram). The effect plateaus at higher levels; 40 mg of citalopram daily (the maximum recommended dose) occupies about 86% of serotonin transporters, while 60 mg daily occupies about 88% of these receptors.

In the context of tapering, this means that the first reduction of antidepressant dose will have minimal biological impact, but as the antidepressant dose gets lower, the ratio of available receptors and neurotransmitters will change more significantly; it’s this chemical imbalance that can lead to withdrawal symptoms that can persist until the receptors adjust to the new biological environment, Horowitz said.

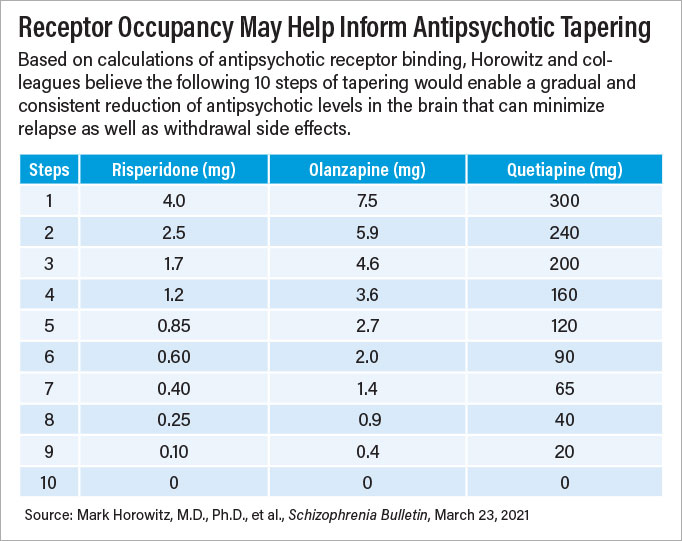

Horowitz and Taylor used the available pharmacological data for antidepressants to develop an “evenly spread” tapering plan: a patient’s antidepressant dose is reduced in a way to produce a consistent reduction of receptor occupancy at each interval, such as 10 reductions of 10% each. Horowitz and Taylor recommend two to four weeks between each dose reduction to see if any withdrawal or relapse symptoms emerge.

“If some symptoms develop, it indicates that the rate of reduction has been too fast,” Horowitz said. “If the symptoms are severe, then the dose should be increased back to where the patient was stable; if [the symptoms] are tolerable, then maintain the current dose until symptoms subside, then proceed more cautiously for the subsequent rounds.”

Near the end of the taper, some medication doses can get to miniscule amounts way below even the smallest pill doses. Horowitz noted that liquid formulations can be useful in such instances since they can be diluted.

After publishing their proposed antidepressant protocol in The Lancet in 2019, Horowitz and Taylor moved on to antipsychotic tapering and published those results this year in Schizophrenia Bulletin. The general principles of evenly reducing receptor occupancy are the same as with antidepressants, though spread over a longer timeframe—about three to six months between dose changes instead of one to two months.

“The effects of antipsychotics on dopamine receptors can be quite persistent,” Horowitz said. He noted studies have shown that some patients with psychosis still had symptoms of tardive dyskinesia—a side effect of antipsychotics—more than two years after stopping their medication.

Tapering antipsychotics could take many months or even years, but Horowitz said that he believes many patients, some of whom have been on an antipsychotic for decades, would be open to a slow taper if it meant possibly eliminating an unnecessary medication.

More Research Needed

“I think our field has overvalued relapse prevention when treating schizophrenia,” said Sandra Steingard, M.D., chief medical officer at Howard Center, a community mental health clinic in Burlington, Vt. “But relapse is just one potential harm that needs to be weighed alongside other harms that medications might cause.”

Steingard, who is now retired, said she discussed the benefits and risks of antipsychotic tapering with dozens of clinically stable patients at her clinic. She found that the patients who expressed interest and began slowly tapering did not experience any worse rates of adverse outcomes such as job loss or hospitalization than those who remained on their full dose. Even several patients on clozapine—which is prescribed to people with severe and treatment-resistant psychosis—managed to significantly reduce their dose without adverse outcomes.

“[I]f patients are insistent on stopping their treatment, we need to let them try using the safest way possible.” —William Carpenter, M.D.

“Patients stop taking their medications all the time without their doctor’s guidance, and that can pose serious risks,” said William Carpenter, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and a leading expert in schizophrenia. Carpenter said that he believes Horowitz’s scientifically supported protocol gives physicians a framework to discuss tapering with a degree of confidence. “We need to work with our patients; if patients are insistent on stopping their treatment, we need to let them try using the safest way possible.”

Carpenter, who is also editor of Schizophrenia Bulletin, said that the antipsychotic tapering data particularly could strike a chord in a professional field that has too long seen schizophrenia as a chronic deteriorating illness. “We now know—and have stated clearly in DSM-5—that schizophrenia is a clinical syndrome with a wide diversity of symptoms. Different patients have different manifestations and different long-term medical needs.”

Steingard acknowledged that a few patients who participated in tapering at her clinic did experience significant relapse during the process, typically before complete discontinuation from the antipsychotic. “It’s not going to work for everybody, but if we could get more rigorous research, we might have a better grasp of the optimal tapering approach to minimize these risks.”

Horowitz, who is a clinical research fellow in psychiatry at University College London (UCL) and the North East London NHS Foundation Trust, is involved in one such study: the Research into Antipsychotic Discontinuation and Reduction (RADAR) trial. This ongoing five-year study, funded by the U.K. National Institute of Health Research and led by Joanna Moncrieff, M.D., a professor of critical and social psychiatry at UCL, has enrolled 250 patients on maintenance antipsychotic therapy for schizophrenia and randomized half of them to gradually taper their medication over 12 months. The RADAR trial will track outcomes in these participants for two years, comparing both relapse rates and social functioning between the two groups.

In the meantime, Horowitz noted that the Royal College of Psychiatrists has adopted the antidepressant tapering protocol that he and Taylor created as their official method for tapering antidepressants. He is hopeful that this group will also adopt the pair’s new antipsychotic protocol.

“I’m both a mental health professional and someone with lived experience of a mental health condition, so I know psychotropic medications are a necessity for some patients,” said Horowitz. “But we should try to make sure each patient takes the lowest dose possible, which in some cases might be zero.”

Horowitz said he has received hundreds of emails from patients and doctors around the world telling him of the success they have had with the slower tapering approach. He is also giving his own antidepressant tapering experiment a second try. ■