FDA Approves Second Antibody Therapy for Alzheimer’s

Abstract

Lecanemab was approved in January under the FDA’s accelerated approval pathway. The medication is meant for individuals with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in January approved lecanemab for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, marking the second approval of an antibody designed to break down Alzheimer’s-associated amyloid plaques in the past 18 months.

Art Walaszek, M.D., says that the slowing of decline seen in patients who took lecanemab is similar to that of medications such as donepezil; the key question is whether the improvements are longer-lasting than current therapies.

Unlike the controversy that surrounded the approval of aducanumab (brand name Aduhelm) in June 2021, the response to the approval of lecanemab (brand name Leqembi) by the scientific community has been relatively quiet. Researchers who spoke with Psychiatric News and others mostly attribute this response to data that suggest lecanemab slows cognitive decline.

“Lecanemab is not a major breakthrough in Alzheimer’s care, but it is the first amyloid-based therapy to demonstrate benefits with respect to cognition,” said Art Walaszek, M.D., a professor and vice chair for education and faculty development of psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine. Walaszek was not involved in the clinical development of lecanemab.

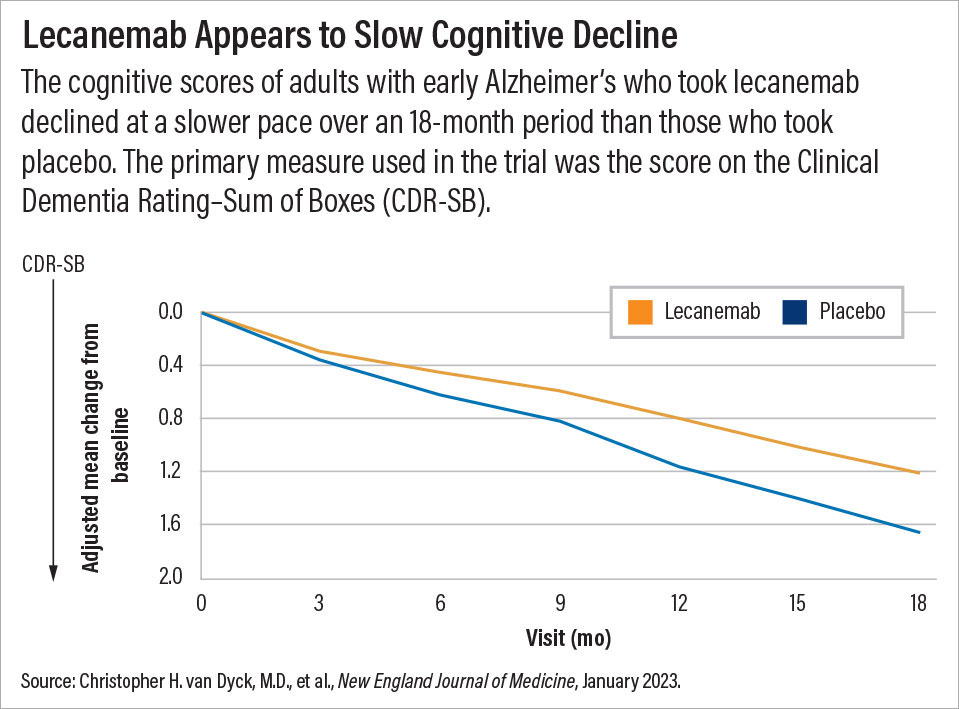

Those benefits were demonstrated in a clinical trial (called Clarity AD) involving nearly 1,800 adults with early stage Alzheimer’s (diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia). On average, the participants who received lecanemab infusions (10 mg/kg) every two weeks demonstrated statistically less cognitive decline over 18 months than those who received placebo infusions. The findings were published January 5 in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

The primary measure used in the trial was the score on the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB). This 18-point scale assesses six domains impacted by dementia (memory, orientation, judgment and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care). The more cognitive impairment that a patient has, the greater his or her CDR-SB score will be.

After 18 months, scores in the lecanemab group rose by 1.2 points compared with about 1.7 points in the placebo group; both groups had average scores of 3.2 at baseline. Secondary cognitive measures showed a similar slowing of decline for adults taking lecanemab. In other words, if the lecanemab-treated patients continued to decline at the same rate after 18 months, they would eventually reach the level of cognitive decline seen in the placebo-treated group, but not until month 25, explained Christopher van Dyck, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and neurology at Yale University and lead author of the NEJM article. Van Dyck has received research support from Biogen and Eisai to conduct clinical trials on both aducanumab and lecanemab.

The most common adverse events (affecting more than 10% of the participants) in the lecanemab group were infusion-related reactions, the authors reported in NEJM. These events included ARIAs, or amyloid-related imaging abnormalities. ARIAs reflect temporary internal swelling or bleeding that occur when amyloid plaques are removed. Most of the ARIAs among participants were considered to be minor and asymptomatic, though some participants reported such symptoms as headaches, blurred vision, and falls.

Walaszek noted that “the rate of ARIAs was lower with lecanemab than aducanemab, so it appears safer, but I would caution these are not data from a head-to-head trial.” He also noted that three trial participants on anticoagulants died from stroke-related events, but it’s not yet clear what role lecanemab played.

Eisai to Seek Traditional FDA Approval

Interestingly, lecanemab was approved by the FDA without factoring in the Clarity AD data. As with aducanumab in 2021, this antibody received accelerated approval based on promising phase 2 biomarker data. Accelerated approval allows companies to speed a drug for a life-threatening illness to market based on a surrogate endpoint that reasonably predicts future clinical benefit to patients. For lecanemab and aducanumab, the surrogate endpoint is reduced amyloid plaques in the brain.

The use of amyloid as a biomarker has been controversial among many researchers, who note there is little evidence linking the degree of amyloid buildup to Alzheimer’s symptoms.

Shortly after the FDA granted the accelerated approval of lecanemab to Eisai Co. (who co-developed lecanemab with Biogen), the company announced plans to submit the data from the phase 3 trial and file for traditional FDA approval.

Traditional approval could be a significant step since an accelerated approval is a conditional status; companies must continue to do post-marketing studies to demonstrate a clinical benefit, and if they fail, then the FDA can withdraw the approval. In addition, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in April 2022 announced that Medicare would not cover any amyloid-based Alzheimer’s therapy with accelerated approval outside of a clinical trial setting. Antibodies with traditional approval will be covered if the patients allow their data to be collected as part of a CMS-approved study. CMS noted it may reconsider its coverage policy of such medications once new data are available.

“What Medicare ultimately has to say will be critical, because there is a health-equity component involved,” said Walaszek. “We know minority groups like Black and Hispanic individuals have higher rates of dementia due to socioeconomic and health disparities; these same disparities reduce their access to professional caregivers or other services.”

But with an estimated annual price of $26,500, lecanemab may be out of reach for many who might benefit, noted van Dyck. “We don’t want lecanemab to become a therapy exclusively for the well-to-do.”

‘The Paradox of Slowing’

Even if out-of-pocket costs for lecanemab were to come down, the medication may not see extensive use, Walaszek cautioned. “First, there are infrastructure issues to consider. A clinic would need to have infusion centers, which are widely available, but may not be able to scale up to accommodate extra patients coming in twice a month.” Clinics that provide lecanemab also need access to PET scans to identify amyloid buildup and MRI scans to periodically test for ARIAs.

“Lecanemab also produces a modest change in cognitive decline, which is comparable to what we see for older Alzheimer’s medications like donepezil or rivastigmine,” he said. The shortcoming of these existing medications is that they only temporarily slow cognitive impairment. “In the lecanemab trial, the separation between the drug and placebo kept increasing over 18 months, which some people believe indicates that lecanemab will have durable effects. I’m not sure if that’s the case, but time will tell how long this benefit lasts.”

There are also important ethical questions to consider, said Kostas Lyketsos, M.D., the Elizabeth Plank Althouse Professor for Alzheimer’s Research at Johns Hopkins Medicine. Lyketsos was not involved in the development of lecanemab but has received past research support and consulting fees from Eisai.

“It’s the paradox of slowing,” he told Psychiatric News. “In the short term, you can keep a patient at a mild dementia stage for six or seven months longer, but that means they will also spend longer in the more disabling stages later on.” At some point, the question will arise on whether lecanemab is prolonging a life worth living.

In addition, since lecanemab is associated with a subtle slowing of cognitive decline rather than a noticeable cognitive improvement, it may be difficult to assess if an individual is benefitting from using the medication, Lyketsos continued. Patients with mild impairment typically do not have enough documented history of decline to try and guess their expected trajectory, he noted.

So, while there is a consensus on when antibody therapy should be started—in the earliest stages of disease—there is no data on when to stop. Looking ahead, Lyketsos thinks Alzheimer’s drug trials will need to include more quality-of-life data for both patients and their caregivers.

In the meantime, the developers of both aducanumab and lecanemab are conducting additional trials that can offer more clinical details. A third antibody that targets amyloid, named donanemab, was recently denied accelerated FDA approval despite positive phase 2 data (the FDA indicated there were not enough patients who stayed on the medication for at least a year); Eli Lilly is continuing with a phase 3 trial and hopes to resubmit a traditional approval.

“I’ve been researching Alzheimer’s for more than 30 years, and the first 20 were often discouraging,” van Dyck said. “But in the past decade, we have seen steady progress into early detection and early intervention for Alzheimer’s.” ■