Problems of ADHD Kids Don’t End When Bell Rings

When one thinks of a child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, one might visualize a youngster fidgeting in his seat at school or racing around the school playground during recess. Yet the behavioral and social handicaps of having ADHD are much more extensive than that, suggests a survey conducted by the New York University Child Study Center. The survey was conducted with parents of children with ADHD and is believed to be the first of its kind.

Last August phone interviews were conducted with 255 parents of children diagnosed with ADHD and with 252 parents of children who had not been so diagnosed to learn how the parents viewed their children insofar as different behaviors and social aspects were concerned. The results from both groups were then compared to determine whether there are certain kinds of behavioral and social problems that ADHD youngsters are more likely to have than those without the disorder. And indeed, there seem to be some, the survey showed.

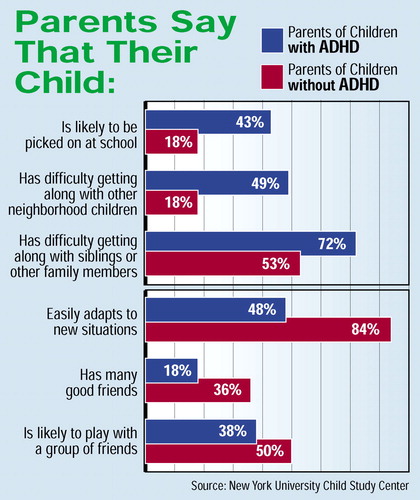

For instance, 43 percent of parents of children with ADHD reported that their youngster was likely to be picked on at school, compared with 18 percent of parents of non-ADHD children. Forty-nine percent of parents of children with ADHD reported that their child had difficulty getting along with neighborhood children, compared with 18 percent of parents of non-ADHD children. Seventy-two percent of parents of ADHD children reported that their offspring had trouble getting along with siblings or other family members, whereas only 53 percent of parents of non-ADHD offspring did (see chart).

For instance, 43 percent of parents of children with ADHD reported that their youngster was likely to be picked on at school, compared with 18 percent of parents of non-ADHD children. Forty-nine percent of parents of children with ADHD reported that their child had difficulty getting along with neighborhood children, compared with 18 percent of parents of non-ADHD children. Seventy-two percent of parents of ADHD children reported that their offspring had trouble getting along with siblings or other family members, whereas only 53 percent of parents of non-ADHD offspring did (see chart).

In general, more parents of children diagnosed with ADHD than parents of non-ADHD ones said that activities such as helping them with their homework (52 percent versus 28 percent), getting them ready for school in the morning (26 percent versus 16 percent), and getting them ready for bed on school nights (27 percent versus 11 percent) required more than one hour per activity. Overall, more than half the parents of ADHD children reported being “very frustrated” or “somewhat frustrated” while helping their child with these activities.

Thus, “ADHD is not just a school-day disorder; it is an all-day disorder,” Harold Koplewicz, M.D., a child psychiatrist and director of the New York University Child Study Center, said in a statement released with the study results. “In addition to its proven impact on academic performance, ADHD also affects how children get along with family and friends, complete homework assignments, and participate in after-school activities. Successful management of this condition needs to address all aspects of a young person’s daily life.”

The survey was sponsored by an unrestricted educational grant from McNeil Consumer and Specialty Pharmaceuticals.

The IMPACT (Investigating the Mindset of Parents About ADHD and Children Today) survey is posted on the Web at www.AboutOurKids.org/articles/impact.html. ▪