Child's Symptoms Abate When Mother's Depression Remits

Children benefited from successful depression treatment of a group of mothers who experienced remission within several months of treatment, a new study has found. Moreover, children of mothers who remained depressed actually developed new psychiatric problems in some cases.

“These findings are intriguing because they suggest that an environmental influence had a measurable impact on the child's psychopathology,” the authors wrote in the March 22/29 Journal of the American Medical Association.

Researchers speculated that maternal depression contributes to a stressful home environment, which can increase the rates of depression and other disorders in children who may already be genetically vulnerable to developing mental health problems.

Lead author Myrna Weissman, Ph.D., and colleagues found an overall 11 percent decrease in rates of psychiatric disorders in children of mothers who experienced remission after treatment. Weissman is a professor of epidemiology and psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center and chief of the Department of Clinical-Genetic Epidemiology at New York State Psychiatric Institute.

In contrast, there was an 8 percent increase in rates of psychiatric diagnoses for children whose mothers continued to experience depressive symptoms.

Weissman told Psychiatric News that she has long been interested in studying the effects of parental depression on children.

“Children of depressed parents have very high rates of depression and other mental health problems,” which continue into adulthood, she noted.“ If you can impact the child by treating the parent, you'd have a twofer.”

Weissman chose to study mothers with depression instead of fathers because depression is more prevalent among women, and more women seek treatment, but she emphasized that either parent's depression can negatively impact children.

She studied 151 mother-child pairs who were part of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, which was conducted between December 2001 and April 2004 among more than 4,000 people in primary care and outpatient psychiatric settings at a number of sites across the country (see Original article: page 42).

The mothers who agreed to be part of Weissman's study had children between the ages of 7 and 17 and received three months of treatment with citalopram at eight primary care and 11 psychiatric clinics across the country. Researchers earlier established a diagnosis of depression using a symptom checklist based on DSM-IV and measured the severity of mothers' depression using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D).

Children in the study were evaluated for psychiatric disorders at the beginning of the study and after their mothers took citalopram for three months. Researchers used the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia–Present and Lifetime Version, the Child Behavioral Checklist (parent report), and the Child Global Assessment Scale to assess psychiatric illness and functioning in children.

At baseline, 37 of the 151 children had a psychiatric disorder, such as depression (10 percent), anxiety (16 percent), or a disruptive behavior disorder (22 percent).

Of the 114 mothers who were assessed after three months of treatment with citalopram, 33 percent (38) met remission criteria and 47 percent (54) responded to treatment, defined as a 50 percent or greater reduction of symptoms as measured by the HAM-D.

Among children whose mothers' depression remitted, one-third of the children experienced remission during the three-month study period.

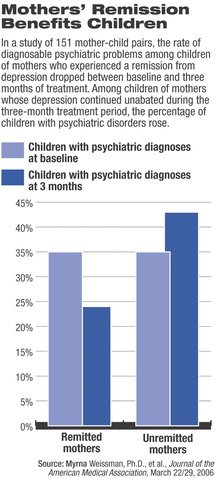

Weissman found an 11 percent drop in the rates of psychiatric disorders among children of mothers who experienced remission from depression. At baseline, 35 percent (12) of the children had a psychiatric diagnosis, and after three months 24 percent (eight) of children did.

Among children of mothers who experienced continuing depression, the rate of psychiatric disorders increased from 35 percent to 43 percent.

According to the article, 68 of the children had no psychiatric diagnosis at baseline. Among children with no baseline diagnosis with mothers who remitted (22), all remained diagnosis free at the three-month assessment.

However, among children with no baseline diagnosis but with mothers who did not remit, 17 percent (eight) developed a new psychiatric disorder or experienced a recurrence of symptoms from a previously diagnosed disorder.

Weissman found mothers' depressive symptoms had to decrease by at least 50 percent for there to be a reduction in children's psychiatric symptoms.

There are a few limitations to the study. “The use of a single antidepressant in an open-trial design without a placebo control did not allow us to rule out that maternal remission was due to nonspecific treatment effects,” the authors wrote, “or whether the relation of maternal remission to children's outcomes may have been different if another medication or psychotherapy had been used.”

In regard to the association between maternal remission from depression and reduced child psychopathology, Weissman speculated that the mothers' remission from depression brought about improvement in children that, in turn, further impacted the mothers in a positive way.

The study's findings add a new urgency to the importance of finding depression treatments that work, according to experts.

“One of the most creative aspects of this study is the assessment of the impact of a remission of depression in mothers on the mental health of their children,” Darrel Regier, M.D., M.P.H., told Psychiatric News. “It brings home the enormous public health impact of successful treatment for this illness.” Regier is director of the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education and APA's Division of Research.

Weissman is currently following the sample to track clinical outcomes in children of mothers who achieve remission after three months of treatment.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.

An abstract of “Remissions in Maternal Depression and Child Psychopathology” is posted at<http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/295/12/1389>.▪

JAMA 2005 295 1389