Mitochondria Malfunction May Underlie Some Severe Psychiatric Disorders

First there were evil spirits, then Freud and psychological theories, then neurotransmitters.

Next up for consideration as a possible source of psychiatric disorder may be mitochondria, the tiny subcellular bodies that provide energy to the body's cells.

A small group of researchers in Sweden, Japan, Britain, the United States, and other countries have been exploring the connection between mitochondria—especially when they are not working properly—and schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, and other conditions.

Any role for mitochondrial dysfunction in elevating the risk for psychiatric disorder remains a hypothesis, but a mix of clinical and laboratory work is starting to clarify the landscape.

Although mitochondria were first described 120 years ago, the first mitochondrial disease was reported only in 1962. Since then, more syndromes have been reported, affecting numerous organ systems, including the brain.

In addition, among their other symptoms, people diagnosed with mitochondrial disease have higher-than-usual rates of psychiatric disorders or symptoms such as depression, visual hallucinations, bipolar disorder, and anxiety, explained William Regenold, M.D., C.M., an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Regenold has been studying glucose metabolism in the brain and speculated that some psychiatric problems might be related to glucose-processing problems involving mitochondria. He and his colleagues decided to look at one biomarker of mitochondrial disease—lactate concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)—in patients with confirmed psychiatric illness. Their paper in the March 15 Biological Psychiatry provides an indication of where the field stands and how far it has to go.

Normally mitochondria in brain neurons and astrocytes produce just enough lactate to meet energy demands but not so much that it accumulates in the brain or the CSF. In people with mitochondrial disorders, however, lactate is produced anaerobically by glycolysis outside the mitochondria, which cannot adequately metabolize it, causing lactate to build up in the CSF.

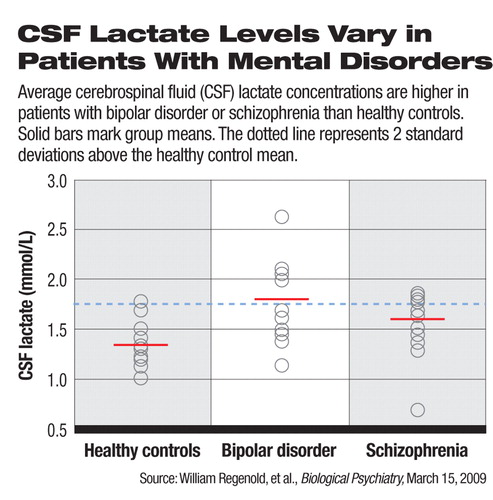

The Maryland researchers measured levels of lactate in the CSF taken from two groups of 15 patients, each diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, and also from 15 healthy controls. Individual lactate levels in the CSF varied, but significantly higher average concentrations were found in the bipolar (+34 percent) and schizophrenia (+23 percent) groups, compared with the healthy controls, said Regenold. Adjusted CSF lactate means were 1.70, 1.64, and 1.35, mmol/L for the bipolar, schizophrenia, and control groups, respectively.

“This indicates that there is something different about these patients,” said Regenold, although questions remain. “We don't know if this difference occurred only at the time they were sick and in the hospital.”

He also considered possible effects of medication or heredity. A number of psychotropic drugs, such as haloperidol and clozapine, show antimitochondrial effects. Twenty-three of the 30 patients were on medication, but the researchers found only a trend toward lower CSF lactate concentration (p=0.058) associated with any antipsychotic use. Also, the only significant effects of family psychiatric history came in the bipolar group in which the five subjects with a family history of psychiatric illness had higher mean lactate levels than those without such a family history.

The results offer at least indirect evidence for the involvement of mitochondrial dysfunction with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, said the researchers, who described the study as the first of its kind.

That the CSF lactate levels associated with the disorders overlap means that mitochondria are not a simple, overall explanation for those psychiatric disorders but may at least play a partial role in some portion of the population, he said. A mitochondrial dysfunction hypothesis may also open a door for a new explanation of some medically unexplained somatic complaints that so commonly get sent to psychiatrists to diagnose.

“We all have patients who don't fit neatly into classic DSM categories,” said Regenold, a geriatric psychiatrist. At the very least, his laboratory research has helped him look more closely at his clinic patients. “You start seeing things in patients you hadn't noticed before.”

For both research and clinical purposes, Regenold would like to see a less-invasive method of measuring CSF lactate levels. Other researchers have used magnetic resonance spectroscopy to quantify those levels, but drawing the fluid with a spinal tap allows more accurate measurement than imaging so far.

Although many questions about the connection between CSF lactate concentrations and psychiatric disorders remain, eventually, wrote Regenold and colleagues, “prevention and amelioration of abnormal metabolism might be an important untapped therapeutic option for some patients.”

The study was partially funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.

An abstract of “Elevated Cerebrospinal Fluid Lactate Concentrations in Patients With Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia: Implications for the Mitochondrial Dysfunction Hypothesis” is posted at<www.journals.elsevierhealth.com/periodicals/bps/article/S0006-3223(08)01404-2/abstract>.▪