Depression, SSRIs Pose Similar Risks in Pregnancy

Depression threatens the health and well-being of pregnant women and their unborn children, but antidepressant treatment carries its own risks. Researchers struggle to better understand the risks associated with antidepressant medications to pregnant women and unborn children and help patients and physicians make individualized decisions.

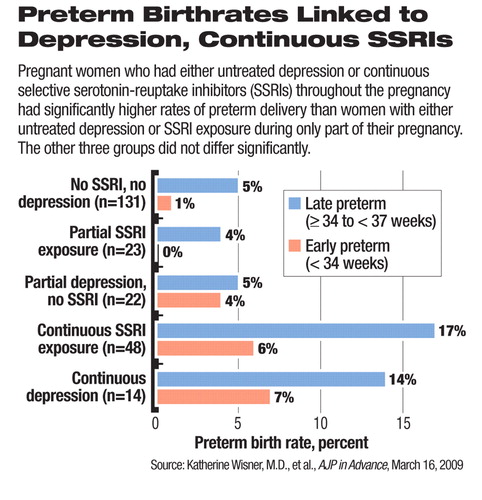

In a study published online in AJP in Advance on March 16, Katherine Wisner, M.D., and colleagues found that pregnant women with continuous untreated depression and those with continuous exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) had similarly elevated rates, of more than 20 percent, of preterm delivery (see chart). These rates were significantly higher than the 4 percent to 9 percent preterm delivery rates in women with SSRI exposure or depression without treatment during only part of the pregnancy. The rates in women with exposure and depression during only part of the pregnancy were not significantly different from those of the control group of women with neither depression nor SSRI exposure.

All study participants had a diagnosis of depression, but symptom severity, measured by the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, was significantly higher in the group who had continuous depression with no SSRI treatment during pregnancy than in the other groups.

“The proportions of late (>34 to 37 weeks) and early (<34 weeks) preterm births were similar ... in women exposed to either continuous major depressive disorder or continuous SSRI treatment throughout pregnancy,” Wisner, a professor of psychiatry, obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences and epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, told Psychiatric News. She is also the director of the Women's Behavioral HealthCARE program at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic of the University Pittsburgh Medical Center.

“Either there is a factor related to the underlying disorder, depression, that increases the risk for preterm birth regardless of whether the depression is treated or not,” Wisner explained, “or a factor related to SSRI exposure, which differs from that related to untreated depression has an equivalent impact on increasing preterm birth.”

“The clinical implication is that a woman [with depression] who declines antidepressant treatment because she is concerned about preterm birth is at a similar risk because of the disease state,” she noted.

Infants' Clinical Outcomes Similar

Furthermore, most other clinical outcomes for the infants did not differ significantly by in utero exposure to SSRIs or depression without treatment. The clinical outcomes of infants, including physical anomalies, birth weight, admission to neonatal intensive care units, and clinical assessments were also similar among the mothers regardless of exposure to SSRIs. Of the assessed clinical risks, only having an Apgar score above 7 at five minutes after birth was significantly higher in the group with continuous SSRI exposure than in the other groups. This study also found no association between SSRI exposure and maternal weight gain.

The study researchers prospectively followed 238 pregnant women through their pregnancy and delivery and compared those who had no depression and took no SSRI (n=131), those who took SSRI either continuously or during part of the pregnancy (n=71), and those who had major depressive disorder and took no SSRI during the pregnancy (n=36). The analyses were based on assessments conducted at weeks 20, 30, and 36 of the pregnancy, at delivery, and two weeks after delivery.

Previous studies have produced inconsistent results. Some evidence suggests that exposure to SSRIs during pregnancy, especially in the late stage, may be associated with increased likelihood of poor clinical outcomes for newborns. Research also suggests that different SSRIs may have different pregnancy risks, and paroxetine and fluoxetine have been most frequently associated with problems in mothers and newborns, the authors noted.

Hypertension Risk Found

In another study published online in AJP in Advance on January 2, Sengwee Toh, M.Sc., of the Harvard School of Public Health and colleagues identified a link between SSRI exposure in late pregnancy and a significantly higher risk for gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. The authors cautioned, however, that the study did not determine the cause and effect in this association.

This retrospective study was based on survey data from nearly 6,000 Massachusetts women who gave birth between 1998 and 2007 and who participated in a large surveillance program for birth defects. The authors acknowledged that they could not have differentiated among the effects of the medications, the mood disorders, and perhaps an interaction of both, because they compared women taking SSRIs and not taking SSRIs during pregnancy without information on their diagnoses.

It is notoriously difficult to determine the cause and effect between pregnancy outcomes and specific medications since randomized, controlled clinical trials cannot be conducted ethically in this context. Physicians and patients have to make decisions based on available data from animal experiments, epidemiological surveillance, and observational studies.

Further complicating the matter is the fact that depression, the risk of which is increased by pregnancy, can have a detrimental effect on the health behaviors of the mother, such as smoking, drinking alcohol, poor nutrition, and poor self-care, which pose health risks to the fetus. The biological effects of the underlying depressive disorder on pregnancy are still poorly understood.

“In medicine, we typically focus more on the risks of medications used to treat disorders than on [the risks of] the disorders themselves during pregnancy,” Wisner emphasized. The good news, however, is that “we now know more about antidepressants during pregnancy than most other classes of medications.”

The Wisner study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health. The Toh study, conducted by researchers at the Slone Epidemiology Center and the pharmacoepidemiology program at the Harvard School of Public Health and the Department of Pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, was not directly funded by any organization or company.

“Major Depression and Antidepressant Treatment: Impact on Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes” is posted at<http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/reprint/appi.ajp.2008.08081170v1>.“ Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Use and Risk of Gestational Hypertension” is posted at<ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/reprint/appi.ajp.2008.08060817v1>.▪