Leading 21st-Century Department Requires Creativity, Patience

Abstract

Develop a niche or area of expertise in psychiatry and stay as informed as possible about new developments in the field by reading psychiatric and other medical journals. Medicine is moving forward at light speed, and no psychiatrist can afford to be left behind. Furthermore, psychiatrists must guard ferociously their unique roles in medicine.

This was some of the wisdom imparted by chairs of psychiatry departments to a group of chief residents who gathered recently at the 40th annual Tarrytown Chief Residents Leadership Conference in Armonk, N.Y. Forty-three psychiatry residency programs were represented at this year’s conference, which is run out of the Continuing Medical Education Center at Montefiore Medical Center (Psychiatric News, February 3).

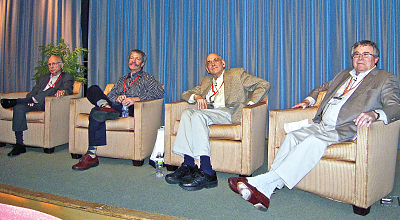

Three psychiatry department chairs (from left, T. Byram Karasu, M.D., Wayne Goodman, M.D., and Jack Barchas, M.D.) share with chief residents their thoughts on the future of leadership in psychiatry. Bruce Schwartz, M.D. (far right), moderated the discussion.

“We must embrace the totality of psychiatry” to preserve its integrity, said Jack Barchas, M.D., one of the conference speakers. Barchas is the Barklie McKee Henry Professor and chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College and psychiatrist in chief of New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center and Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic. “From my perspective, the most important thing we can do as psychiatrists is to reject the notion that the role of the psychiatrist can be fulfilled in 10 minutes with a prescription” and that other aspects of treatment can be handled by nonphysician mental health professionals. “We must fight for the totality of our field. We cannot abandon certain aspects of our roles just because the managed care companies are pressuring us to do so,” Barchas remarked.

Wayne Goodman, M.D., concurred and advised the chief residents to further enhance their roles as psychiatrists by working closely with and/or assuming some of the duties typically undertaken by primary care physicians to manage “some of the common medical problems that we encounter in our patients—and not just the medical problems we may bring about with our prescriptions.” Goodman is department chair and the Esther and Joseph Klingenstein Professor of Psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

“Psychiatry must redefine itself,” said T. Byram Karasu, M.D., the Silverman Professor and chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and psychiatrist in chief at Montefiore Medical Center. Karasu recalled a time during his residency training when many psychiatrists exclusively practiced psychotherapy, a role since assumed largely by social workers and psychologists.

“Even the prescription of psychotropic drugs has been assumed by family physicians and other medical specialties,” he added. “We need to convince government officials and insurance companies that we can fulfill a role that is essential and unique to us.”

While the trajectory of the field is ever-changing and unpredictable, the chairs pointed out, so are the trajectories of the individual careers of chief residents.

“It is not very likely that you will be able to plan your professional careers very far in advance,” Goodman told the residents, adding that happenstance, unexpected opportunities, and even career-related disappointments can strongly influence one’s career path.

In Goodman’s case, his quest to uncover the mysteries shrouding obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) has provided an overarching theme to his career, leading him from Yale University to the University of Florida in Gainesville to the National Institute of Mental Health, where he directed the Division of Adult Translational Research and Treatment Development, and finally to his current role as chair of psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, a position he’s held since 2009.

“For myself and others I know, the road to becoming an academic chair came about through leadership and achievement in one area of research.” Goodman admitted that through trial and error, he has been able to hone his administrative skills, and that while he has had to reduce the amount of time spent researching OCD in his current role, he is still able to continue seeing patients with the disorder and teach others about it as well. Goodman said he sees his career trajectory as a “maturation process,” since much of his energy is now devoted to helping others realize their potential. “As you go through [the process], you realize, ‘it’s not just about my research anymore—it’s about cultivating that of others.’ ”

Should the chief residents eventually strive toward and succeed in chairing departments of psychiatry themselves, the chairs at the conference agreed that fairness, patience, and creativity were assets that would prove invaluable to the job.

The chairs also acknowledged some of the challenges they have faced as academic psychiatry leaders.

Karasu said he sees himself as a “shock absorber” for the department as he strives to keep the daily stresses of his job—budgetary concerns, academic competition, and space limitations, for example—from negatively impacting his faculty members and trainees.

Goodman likened his role to that of “running a small business” but having only limited power. “Know that since some aspects of academic psychiatry are standardized across departments,” chairs cannot always make the changes they would like. Barchas in part likened his role to a game of “three-dimensional chess,” in which he puts his creative problem-solving skills to work in a multitude of situations. “This is part of the fun of the role for me,” he noted. “I find that I truly love my job—we as chairs are in the position to help some extraordinary people to realize their full potential.”