Abused Substances Differ in Rural, Urban Areas

Abstract

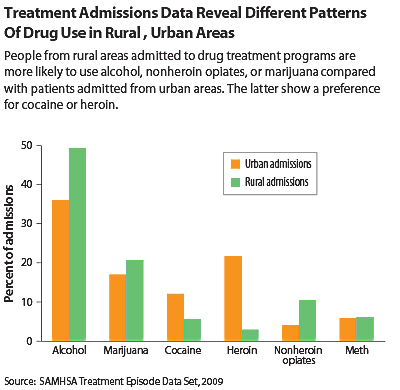

Alcohol and nonheroin opiates are the drugs of choice in rural populations presenting for substance abuse treatment in the United States, while heroin and cocaine top the list in urban areas, according to a new report from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

The Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) report covers admissions to publicly funded or licensed substance abuse programs, with data reported by states.

“Rural admissions were more likely than urban admissions to report primary abuse of alcohol (49.5 vs. 36.1 percent) or nonheroin opiates (10.6 vs. 4.0 percent),” said the July 31 report, which used data from 2009.

The statistics also showed that “urban admissions were more likely than rural admissions to report primary abuse of heroin (21.8 vs. 3.1 percent) or cocaine (11.9 vs. 5.6 percent).”

Methamphetamine rates were nearly equal (urban, 6.1 percent, and rural, 6.3 percent) despite the common assumption that meth is largely a rural problem. Data also showed that rural dwellers used marijuana slightly more than city people did.

The higher usage rates of alcohol and nonheroin opiates among people admitted in rural areas may reflect accessibility issues, said H. Wesley Clark, M.D., J.D., M.P.H., director of SAMHSA’s Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. “Illegal drugs may be harder to conceal in the pipeline to rural areas, or legal substances may be less stigmatized.”

The different treatment admission patterns can help clinicians and policymakers direct resources for treatment and preventive efforts, said rural health specialist Snehal Bhatt, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of New Mexico and medical director of its Addiction and Substance Abuse Program.

However, it’s important not to overgeneralize,” Bhatt told Psychiatric News. “Even in urban areas, rates of alcohol treatment are still pretty high,” he said. “It’s important to target interventions geographically, but we shouldn’t lose sight of the bigger picture, that the need for treatment is widespread.”

The TEDS data show some differences in age and referral patterns too.

Admitted rural users were less likely to use substances on a daily basis, but they began using substances at an earlier age than their urban counterparts. About 67 percent started before age 18, while 53 percent of admitted urban users started using substances prior to that age.

That may be reflected in higher rural rates of binge drinking and driving under the influence among young rural people than urban youths, according to a study of adolescent alcohol use published in March by the Maine Rural Health Research Center at the Muskie School of Public Service at the University of Southern Maine.

“[R]ural youth, their families and peers are less likely to disapprove of youth drinking than [are] urban youth, risk factors that are associated with greater likelihood of adolescent alcohol use,” wrote John Gale, M.S., a research associate at the center, and colleagues.

Also, more admitted rural users were referred to treatment by the criminal-justice system than was the case in urban areas.

More referrals from the criminal-justice system could be good news or bad.

Given that self-referral is lower in rural areas, said Bhatt, “then someone has to pick up the slack,” and in those areas that may be the criminal-justice system.

To the extent that substance abuse affects the wider community, criminal-justice involvement is beneficial, however. Lower rates of self-referral and less access to outpatient treatment may mean that an individual abuser falls further down the ladder until they do something that gets them arrested, Bhatt suggested.

Finally, rates of admissions for prescription opiate abuse largely reflect diversion of those drugs, said Bhatt. In general, about 67 percent of them are obtained from friends or the family medicine cabinet.

“That means they’re ultimately getting them from doctors,” said Bhatt. “We have to do more outreach to both the medical and the general community about controlling access to these drugs.”

In rural areas there also is a serious shortage of substance abuse specialists, but primary care clinicians—with some additional training—can manage patients needing substance abuse treatment, said Bhatt.

In the end, though, country or city may not make much difference.

There are users and dealers everywhere, said Clark. “Just because you live in a rural area doesn’t mean that you’re immune from these problems.”

“A Comparison of Rural and Urban Substance Abuse Treatment Admissions” is posted at www.samhsa.gov/data/2k12/TEDS_043/TEDSShortReport043UrbanRuralAdmissions2012.htm.