Why Is Naltrexone Not Used More to Treat Alcohol Use Disorder?

Abstract

Despite evidence to suggest naltrexone can help patients drink less and less often, some professionals have been slow to embrace the idea that pharmacotherapy can help patients with alcohol use disorder.

A 50-year-old man with a history of alcohol abuse that began in adolescence tells his physician, “I’ve tried AA, and it just doesn’t work.” In fact, he may have had months or even years of sobriety and active involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), but he repeatedly relapses with progressively worse outcomes.

Many physicians have met this type of patient or someone quite similar, yet they often refer patients with alcohol use disorder to alcohol rehabilitation centers, which tend to rely heavily on the 12-step model of recovery made popular by AA.

In recent years, there has emerged a body of evidence that medication—especially naltrexone, but also acamprosate—can be effective for many patients with alcohol use disorder.

In June 2015, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration released a pocket guide to medication-assisted treatment of substance use disorders including alcohol use disorder. (APA is a partner organization in Providers’ Clinical Support System for Medication-Assisted Treatment, a consortium of groups focused on training physicians in medication-assisted treatment.)

A 2014 meta-analysis of 122 randomized, controlled trials and one cohort study on the use of naltrexone or acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol use disorder found that both drugs were associated with a reduction in return to drinking. The article, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, concluded that for oral naltrexone (50 mg/day), the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent return to heavy drinking was 12.

“We have to treat 12 people with naltrexone to get one to successfully reduce drinking,” said study author Dan Jonas, M.D., M.P.H., in an interview with JAMA after the study appeared. “People look at that two ways—some may not view it as very good, but those numbers are pretty good compared with other medications that have wide support.” For instance, a 2011 Cochrane Review in the British Medical Journal on the effectiveness of statins found that for low-risk patients, the number needed to treat to prevent one death per year was 1,000.

The JAMA finding illustrates what clinicians who spoke with Psychiatric News emphasized—naltrexone is not by any means a “cure” for alcohol use disorder, and not every patient will respond. By binding to opioid receptors in the brain, the medication reduces the pleasure associated with alcohol and thereby diminishes craving—so its proven effect is primarily on the number of heavy drinking days.

When directly comparing acamprosate with naltrexone for controlling alcohol consumption, no significant differences were found between the medications. There are, however, important dosing differences between the two medications. Oral naltrexone requires one pill per day, while acamprosate requires two pills three times a day. An injectable form of naltrexone can be given once a month. For the purposes of this article, Psychiatric News spoke with clinicians only about naltrexone.

Contributing Factors to Naltrexone Underuse

All clinicians who spoke with Psychiatric News agreed that abstinence is ideal, and in almost every case they counsel patients to strive for abstinence. Naltrexone has been shown to be effective in helping patients drink less and drink less often. Less drinking means better overall health and fewer social, occupational, and legal consequences for the individual, and lower costs to the health care system.

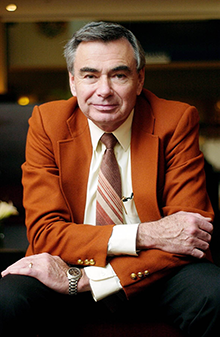

Charles O’Brien, M.D., Ph.D., said there is no reason that clinicians can’t use naltrexone in conjunction with AA participation or any other psychosocial treatment.

Despite positive results, Charles O’Brien, M.D., Ph.D., one of the original researchers on naltrexone for alcohol use disorder and chair of the DSM-5 Work Group on Substance-Related Disorders, said the medication is vastly underutilized.

There are several reasons for underutilization of naltrexone, O’Brien and other experts told Psychiatric News: for example, many physicians are unfamiliar with the medication, and alcohol rehabilitation centers are not typically staffed by medical professionals. But most important, they said, is the longstanding conviction—widely held among physicians as well as the general public—that people with alcohol use disorder can be treated only by the 12-step recovery model.

“There is a political issue here, and the issue is that until relatively recently the medical profession had little to offer alcoholics, and it was during that period that Alcoholics Anonymous developed,” O’Brien said. “Today, there are 1,000 different AA groups in the Philadelphia area, and they tend to be naturally opposed to medication. When I send a patient to a rehabilitation center, they follow the 12-step program.” He added that many counsellors in rehab centers are likely to advise patients not to use medication.

John Renner, M.D., co-chair of APA’s Council on Addiction Psychiatry, agreed. “There is very good evidence showing that if you compare naltrexone with placebo, you get much better sobriety,” he said. “But the general attitude in the recovery community is a very strong preference for a very early version of AA that is uncomfortable with medication.”

Prescribing Naltrexone as Part of Psychosocial Treatment

There is no reason that clinicians can’t use naltrexone in conjunction with AA participation or any other psychosocial treatment, O’Brien said. “We always recommend cognitive-behavioral therapy and/or 12 step,” he said.

“There is a mindset among the public and clinicians that the only way to approach alcoholism is AA, and that physicians and medication have no role,” said Renner. “Doctors just aren’t used to thinking about pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder, and we have had difficulty getting buy-in from general physicians.”

Another challenge to prescribing naltrexone as part of a psychosocial treatment, said addiction psychiatrist Marc Galanter, M.D., is that most general physicians have limited time for counseling. Meanwhile, rehabilitation centers do not typically have physicians on staff, so coordination of psychosocial and medical treatment is poor, he said.

Galanter pointed to the 2014 JAMA study as a reminder that naltrexone “is not penicillin for pneumonia.” He added, “It has a modest to moderate effect on the number of heavy drinking days when compared with placebo.”

But he also sees another benefit to naltrexone. “It has leant material credibility to alcoholism as a physiologically based problem,” he said. “It legitimizes alcohol use disorder as a medical illness.”

Galanter has pioneered research looking at the effects of involvement in 12-step programs and spirituality on the brain. He has also urged psychiatrists to become familiar with AA.

And Galanter says he believes the 12-step community is less biased against medication than it may have once been. “AA in its founding principles says the medication an individual takes is a matter between the individual and his or her doctor,” he said. “It’s true that culturally and historically there has been a bias against medication, but I think that’s less so today.

“Naltrexone can definitely be useful, but we are far from having a definitive medication,” Galanter said. “What that leaves us with is the fact that we have to also use either psychotherapy or 12-step interventions in conjunction with medication.” ■