Confiding in Others May Prevent Depression

Abstract

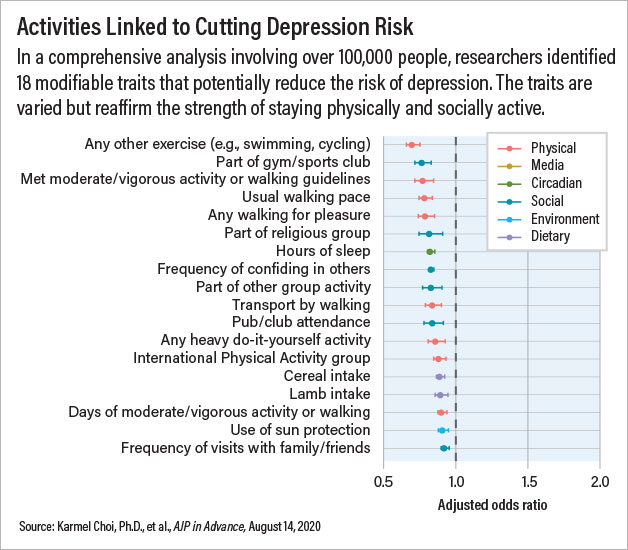

The analysis of 106 modifiable risk factors related to lifestyle and the environment also affirmed excess media use was a significant depression risk.

Engaging in exercise, getting a good night’s sleep, and limiting alcohol consumption have long been recognized as preventive strategies to reduce the onset of depression. Now, a study in AJP in Advance suggests that the most impactful activity a person can do to prevent depression is to confide in others.

The finding comes from a large-scale assessment of the positive and negative effects of 106 environmental, social, and lifestyle traits associated with depression.

“[Confiding in others] was far and away the most protective variable we uncovered in our sample,” said senior study author Jordan Smoller, M.D., Sc.D., a professor of psychiatry and the MGH Trustees Endowed Chair in Psychiatric Neuroscience at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“In the therapeutic context, we know that a trusted, confiding connection is a key component of effective psychotherapy,” Smoller told Psychiatric News. “Now we see its role in prevention may be equally as important.”

Smoller and his team made use of the U.K. Biobank, a collection of genetic samples and health and lifestyle information from over 500,000 adults in the United Kingdom. For their analysis, the researchers focused on data from 118,378 adults of White British ancestry who did not have depressive symptoms at the time they enrolled in the Biobank and completed a mental health survey six to eight years after enrollment. The researchers analyzed the relationship between participants’ behavioral habits (for example, sleep, media use, diet, and exercise), social interactions, and environment with risk of depression at follow-up.

Lead study author Karmel Choi, Ph.D., a clinical and research fellow in Smoller’s laboratory, told Psychiatric News that the team wanted to cast a broad net and provide the most comprehensive picture on potential modifiable factors for depression, which clinicians could refer to when counseling patients at risk. Many of the 106 selected traits overlapped, which also enabled the researchers to see how certain traits interacted (for example, the team not only assessed the benefits of exercising or being part of a social group, but also belonging to a gym, which incorporates both physical activity and social elements).

After adjusting for sociodemographic and physical health differences, 29 traits were found to be associated with subsequent depression risk; 18 of these were protective factors and 11 were risk factors. Among the top protective factors were confiding in others, good sleep hygiene, exercises such as swimming or cycling, and belonging to a gym. The top risk factors for future depression included daytime napping and three media-related traits: time spent on a computer, time spent on a cell phone, and time spent watching TV.

“Of course, correlation is not causation and when you compare a potential cause and effect and that effect is years apart, it’s possible that other events made a contribution in the intervening years,” Smoller explained. To further examine the relationship between the 29 traits highlighted in the study and depression, the investigators employed a technique called Mendelian randomization.

Using genetic information from several existing genome studies, the team identified genetic variants associated with each trait (for example, variants that tend to cluster in people who exercise a lot). Since a person’s genes do not change over the course of six years, these variants are used as proxies to study the influence of a particular trait without the influence of external variables. They next analyzed whether the trait-associated variants influenced depression risk in a proportional manner (for example, whether or not people with genetic variants most strongly linked with exercise have a lower risk of depression compared with people without these variants). A proportional effect suggests the trait in question is directly involved in the protection or risk.

As a complementary approach, the investigators also identified genetic variants associated with depression to test whether depression influences people’s propensity to certain traits.

The Mendelian randomization again pointed to confiding in others as protective against future depression and watching TV as a risk factor for future depression. Daytime napping had a bidirectional relationship; excess napping was a risk factor for future depression, but depression was also a risk factor for excess napping. Taking multivitamins was also found to be a risk factor for future depression—a connection the investigators noted interest in probing further.

The benefits of confiding in others may be more powerful for preventing depression than simply having a big social circle or spending time with others, Choi said. “It’s more about having someone available you can trust.” She noted that a previous study she and Smoller conducted found that military personnel had a lower risk of developing depression under stress if they felt strong social cohesion with their unit—that is, had trusted bonds with people around them.

“The value of confiding is timely given the need for physical distancing [during COVID-19] and the loss of many traditional social outlets,” Smoller said. “Social networks are smaller, but if you can maintain connections any way you safely can, it may make a big difference for your mental health.”

The researchers were supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, the Demarest Lloyd Jr. Foundation, and the U.K. National Institutes of Health Research. ■

“An Exposure-Wide and Mendelian Randomization Approach to Identifying Modifiable Factors for the Prevention of Depression” is posted here.