Cultural Diversity Curriculum Covers All Residency Years

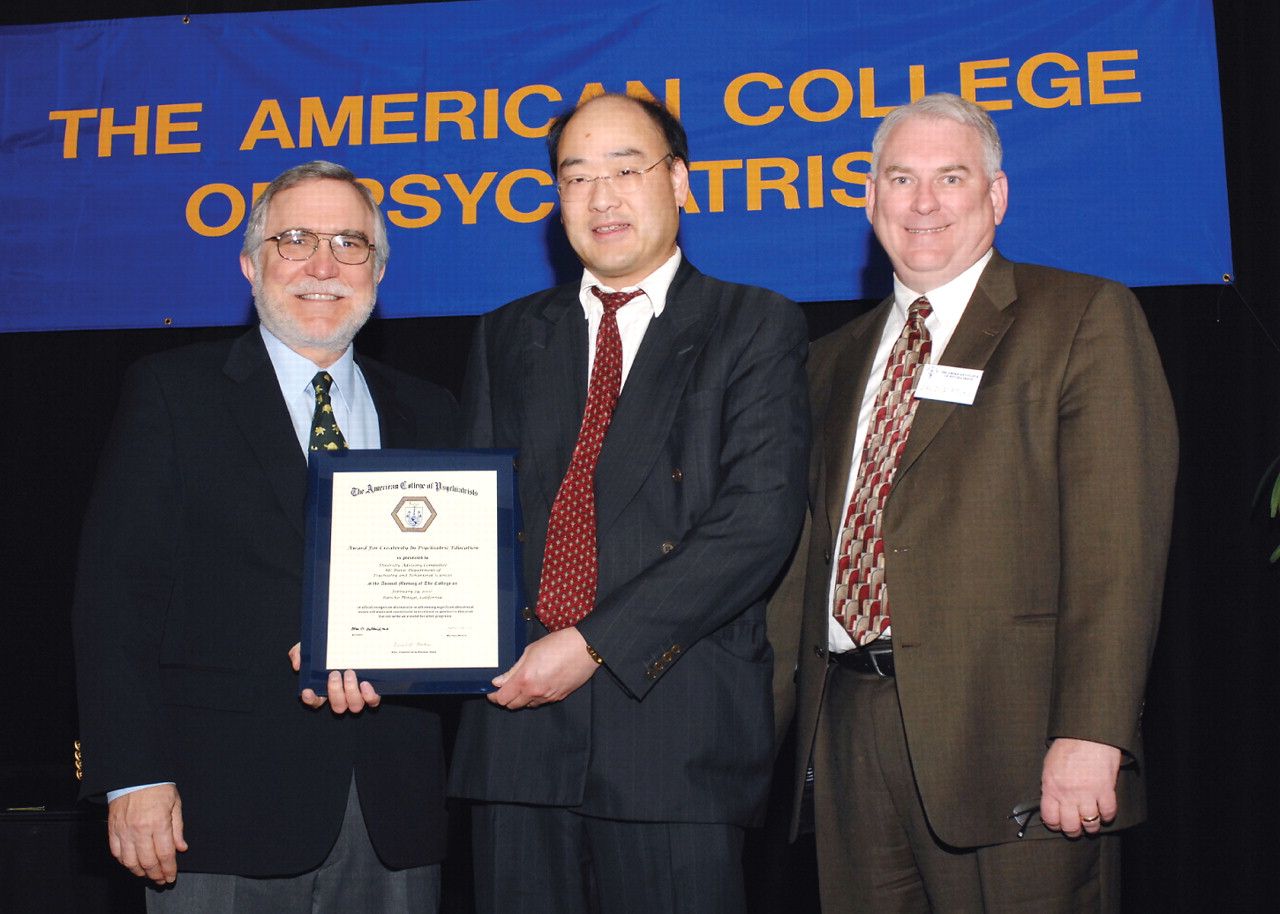

Russell Lim, M.D. (middle), accepts an award on behalf of the UC Davis Diversity Advisory Committee from the American College of Psychiatrists presented by Robert Fernandez, M.D., the first vice president of the college (left), and David Folks, M.D., chair of the Committee on the Education Award. The award lauds the Diversity Advisory Committee for creating a model curriculum for medical students, residents, fellows, and faculty at UC Davis.

Credit: Herman Farrer Photography

By combining clinical experience with carefully planned didactics, educators at the University of California (UC), Davis, have created an award-winning program to address the cultural needs of patients in the ethnically diverse Sacramento area.

“Our goal is to improve the quality of patient care by teaching medical students, residents, and faculty culturally appropriate diagnosis and treatment,” Russell Lim, M.D., told Psychiatric News. Lim is an associate clinical professor and director of diversity education and training in the UC Davis Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.

“The curriculum links clinical services for ethnic minorities, as well as supervision by culturally competent attendings, and the administrative support of our department. Residents get to apply what they learn, and what they learn is reinforced in supervision,” he noted.

Psychiatry faculty and residents developed the Diversity Advisory Committee in 1999 to enhance diversity education for medical students, residents, and fellows at UC Davis School of Medicine. Committee members immediately began to develop different aspects of the curriculum. They also recruit minority medical students and residents to the school's Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.

In March, the Diversity Advisory Committee received the American College of Psychiatrists' Award for Creativity in Psychiatric Education at the organization's annual meeting in Rancho Mirage, Calif.

The UC Davis psychiatry program includes a specialized curriculum for medical students, four-year residency curricula in cultural psychiatry and in religion and spirituality, and specialized training for child and adolescent fellows and faculty in cultural diversity. In addition, the department sponsors minority fellows through the APA/SAMHSA and APA/AstraZeneca minority fellowship programs.

Prior to the establishment of the committee, the department offered only one six-session course in cultural issues to PGY-2 residents.

Culture Shared Among Medical Students

UC Davis medical students are the first to benefit from the cultural training.

After the UC Davis Medical School received a $150,000, three-year grant from the Association of American Medical Colleges several years ago to study the incorporation of cultural principles in medical school education, Diversity Advisory Committee Vice Chair Hendry Ton, M.D., a co-investigator for the grant, used the funding to implement the cultural training for medical students.

“We wanted to align the new material with what they were already experiencing as medical students,” Ton told Psychiatric News. Ton is an assistant professor of psychiatry and director of education at the Center for Health Disparities at the UC Davis School of Medicine.

For instance, medical students meet in small groups for their first three years of school, so their first experience in learning about culture takes place in a small-group format, Ton said. “The students begin by learning about culture as a shared phenomenon.”

In one exercise, first-year students are instructed, for example, to ask an elder member of their family what foods were an essential part of family life through the years and whether recipes had to be modified after the family came to the United States due to the lack of availability of certain ingredients. The exercise culminates in a culinary adventure for all, as students prepare the recipes handed down in their families.

The students also query older family members about the meaning of illness and death within the family, Ton said, which helps them understand patients'“ illness narratives”—how they have been socialized to view illness. There is also a series of seminars on “broader societal issues such as racism and how they affect health care,” he noted.

Second-year students attend a seminar on the impact of language on clinical interaction and use of interpreters with standardized patients. Third-year students apply what they have learned to clinical interactions with patients.

During their psychiatry clerkships, medical students attend a lecture on the influence of culture on diagnosis and treatment, and in OB/GYN clerkships they learn how to complete a cultural assessment with patients on the labor and delivery service.

There is also a course for fourth-year students called “Culture, Medicine, and Society,” which combines didactics and clinical experience.

Ton acknowledged that the students sometimes run into problems with applying what they have learned in clinical settings. Students' preceptors may not be culturally competent, he noted, or clinic administrators balk at the use of interpreters in certain instances.

With those difficulties in mind, Ton has formulated a 16-hour course for health care administrators and clinicians on enabling their organizations to adopt more culturally and linguistically appropriate standards so that medical students and residents have an easier time applying what they've learned to patient care.

Residents Included in Curriculum

Since the Diversity Advisory Committee came to be, psychiatry residents have benefited from the enhanced curriculum.

For instance, PGY-1 psychiatry residents participate in a five-session introduction to cultural psychiatry. PGY-2 residents take an 11-session course in which they learn about mental illness and cultural norms and ways in which people from different racial and ethnic groups may experience symptoms of mental illness and metabolize certain medications.

Gay/lesbian/bisexual/transgender issues are also part of the PGY-2 course.

PGY-3 residents take a course titled “Psychotherapy and Cultural Experience” led by Lim, in which residents learn about key issues in psychotherapy and about personal experiences of faculty with immigration, acculturation, and racism. Residents watch a videotape by the late Irma Bland, M.D., on conducting psychotherapy with African-American patients.

PGY-4 residents take a course in advanced cultural psychiatry led by Lim and David Gellerman, M.D., Ph.D., and learn how to apply the“ DSM-IV-TR Outline for Cultural Formulation” to a patient from their caseloads and write about the case for discussion with a cultural consultant from the Sacramento area, Lim said.

“Residents are often surprised to discover information they did not gather from the patient,” thanks to insights offered by the consultant, he noted.

According to Lim, Sacramento provides plenty of opportunities to work with patients from different racial and ethnic backgrounds. Dubbed “America's most integrated city” in 2002 by Time magazine, the city is home to a large population of Spanish-speaking residents, as well as Asian, Russian, and Eastern-European immigrants.

Religion, Spirituality Addressed

In addition to learning about different cultures, psychiatry residents receive training in religion and spirituality throughout their four-year training program.

PGY-1 residents learn how to conduct a spiritual assessment and delve into patients' views on death and dying, said Gellerman, who developed the religion and spirituality curriculum. Residents also learn how religion and spirituality may be relevant for those with problems related to substance abuse or posttraumatic stress disorder.

PGY-3 residents learn how to discuss spirituality during psychotherapy, and PGY-4 residents discuss more esoteric topics such as transpersonal psychiatry or pain management through meditation.

Gellerman supervises medical students, interns, and senior psychiatry residents rotating through the mental health consultation and liaison service at the Sacramento VA Medical Center.

In addition, for the first time last year, child and adolescent psychiatry fellows at UC Davis benefited from the curriculum through a 12-week course called “Family, Culture, Gender, and Society.” During the course, according to David Rue, M.D., who developed it with the help of other faculty members, fellows complete clinical rotations at mental health clinics throughout Sacramento and work with families from a wide variety of racial and ethnic backgrounds.

During the course, faculty instruct fellows on the diagnosis and treatment of children of immigrants from different racial and ethnic backgrounds (including undocumented families and children).

The course also instructs fellows on working with children of same-sex parents.

The chair of the UC Davis psychiatry department, Robert Hales, M.D., provides the Diversity Advisory Committee with a yearly budget to invite experts in cultural psychiatry to present at grand rounds so that faculty can stay abreast of cultural issues as well. Hales is also editor in chief of American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.

There are also faculty development seminars in which experts on cultural psychiatry train faculty for half-day sessions on topics such as ethnopsychopharmacology and the mental health of refugees.

To stimulate discussion on cultural issues between faculty and committee members, the committee began a journal club and a monthly case conference using the “DSM-IV-TR Outline for Cultural Formulation.”

“Our mission was to improve cultural competence in education and thus reduce mental health disparities in our patients,” Lim said. “I think we're accomplishing that with this curriculum, as our residents are better trained to work with ethnic minority patients, who in turn receive better care.” ▪